Andrew Swanston

THE KING’S RETURN

2014

April 1661

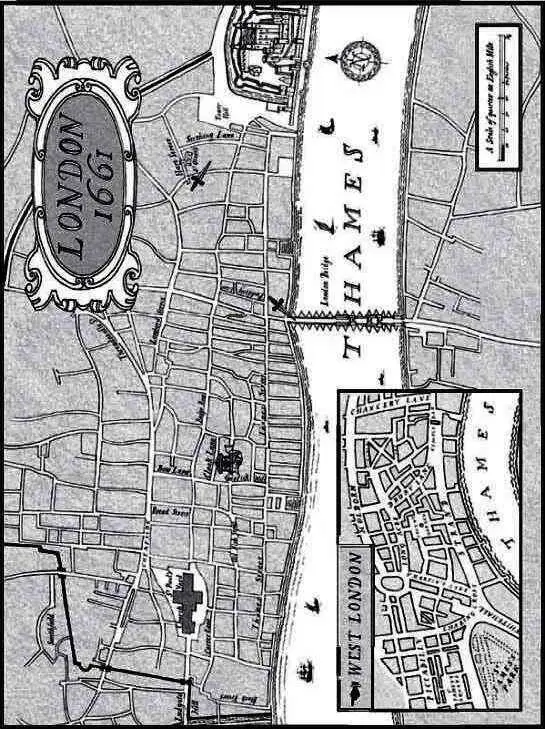

FOR AN HOUR the Dutchman had been standing silent and unmoving in the doorway of a derelict house halfway down the lane. He was hooded and wore black leather gloves, a black coat and soft leather boots. Neither the waiting nor the chill of the night bothered him – he was used to such things – and he would stay there until midnight if he had to. Nor was he concerned at using this lane again. It had served well enough the first time, it was dark and quiet and he had taken up his position early to make sure that there was no one about and to accustom his eyes to the dark.

He had collected his instructions from the usual place behind a loose brick on the side of an inn in Bishopsgate that he checked at a different time every day. This was his second task since arriving from Holland at the end of March. He hoped there would be more.

The bells of a church somewhere in the city signalled ten o’clock. The mark was due. The Dutchman removed a long-bladed knife from inside his coat and carefully tested the edge with his thumb. Not that there was any need – he had whetted the blade himself and knew that it would cut almost anything short of steel – it was just a habit acquired over ten years of perfecting his craft. Ten years in which he had never failed to carry out a commission successfully.

From his left the Dutchman heard footsteps on the cobbles – not the brisk steps of a man returning home or a constable, more the shambling gait of a drinker trying to find his way without falling over, or an elderly man uncertain of his balance. His information was that the mark was elderly. A small man, he had been told, slightly stooped and poor of eyesight. Not a man likely to give him any trouble. He touched his damaged face and smiled. He liked easy money as much as he liked killing Englishmen.

The Dutchman lowered his head, backed into the doorway a little more and waited for the footsteps to pass him. When they did, he looked up from under his hood. A stooped man was shuffling down the other side of the lane towards the river. He knew that his mark would wait at the end of the lane for the man he expected to meet to emerge from the Honest Wherryman tavern. The mark would be watching the tavern door and would not see his attacker approaching from the shadows on the other side of the lane. He had no idea how an elderly man had been persuaded to come to such a place at night, nor did he care.

He slipped out of the doorway and down the lane, keeping ten yards or so behind the mark. He watched the man reach the tavern and stand outside it. For a moment he looked as if he was about to go inside, but then he moved on. The Dutchman closed the gap between them, glanced about to be sure there was no one else in the lane, and when he was no more than five yards away, darted forward, grabbed the old man’s hair, pulled his head back to expose his throat and with one swift stroke opened his windpipe. A fountain of blood spurted from the wound. It was done so cleanly and so fast that the victim uttered not a sound. The Dutchman lowered the body on to the cobbles, then wiped his blade on the man’s coat and patted his pockets. He extracted the dead man’s purse and pocket watch and turned back up the lane. To the coroner the murder would look like the work of a robber.

The mark was dead and there was nothing to connect the Dutchman or his paymaster to his murder. Within thirty minutes he was back in the house in Wapping that had been provided for him.

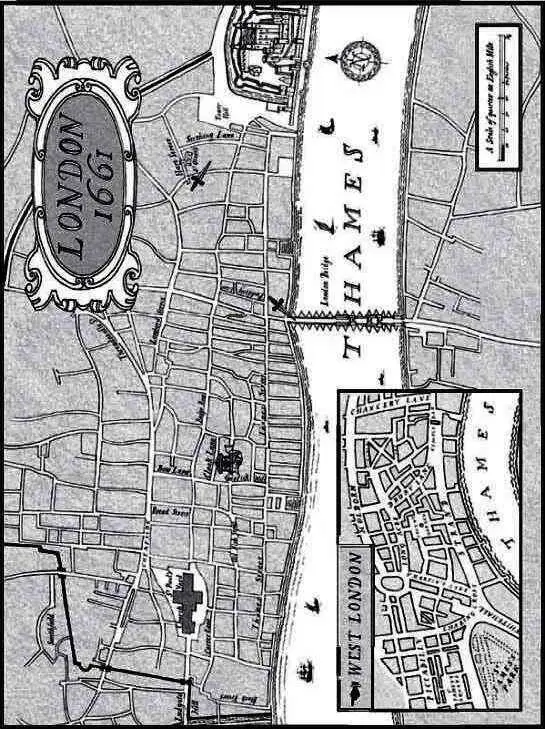

THE CARRIAGE IN which Thomas Hill sat – as a gentleman should, with his back to the coachman – rattled over the Southwark cobbles towards London Bridge. After three uncomfortable days Thomas’s backside was sore and his temper short. Holding a lavender-scented handkerchief to his sensitive nose, he leaned out of the window and shouted at the coachman to stop. Among the beggars, urchins and street vendors, he had spotted a mercury selling news-sheets. Thomas summoned the boy and handed over three pence.

The front page of the news-sheet was devoted, unsurprisingly, to the coronation and the magnificent procession which would precede it. On the eve of his coronation, King Charles II would proceed with his knights and bishops from the Tower to Whitehall, under arches erected especially for the occasion, and past a naval display at the Royal Exchange, a Temple of Concord in Cheapside and a Garden of Plenty in Fleet Street. The king was a man who, like his devout Catholic mother, Queen Henrietta Maria, understood the importance of ceremony, the more extravagant the better. That tiny, formidable lady had led an army of three thousand men to Oxford and had dressed and lived as a soldier, yet could spend thousands on entertainments for the king. For her son, the streets had been cleaned and gravelled and rails erected to keep the crowd a suitable distance from the royal party. Thousands were expected to line the route.

As for the coronation itself, the writer described in fulsome detail what the new king would be wearing, who, with his brother James, would accompany him, and what the ceremony, designed by the Garter King of Arms himself, would entail. And he reminded his readers that, had he not died of smallpox six months earlier, the king’s brother Henry would also have been at his side.

As Thomas read on, he learned who had made the royal shoes, the royal wig and each item of His Majesty’s magnificent coronation robes. The people of London were about to witness the grandest ceremony the city had ever seen, as befitted a monarch restored to his rightful throne after twelve years of dreary Puritanism, and the great day, the day for which all of England had been waiting, would end with a wondrous display of fireworks. Thomas disliked fireworks and hoped that he would not be expected to attend. The coronation itself would be quite sufficient.

When he turned the page, Thomas’s eye was immediately caught by the headline of the next story.

ANOTHER MURDER IN PUDDING LANE

Sir Montford Babb found dead

Coroner believes robbery again the motive

Thomas caught his breath. There used to be Babbs in Hampshire and he remembered Sir Montford as a rather vague, kindly man, not a man you would expect to find with his throat cut in a filthy London alley. And he was surprised to find the murder of a single unknown man reported in the news-sheet, especially when those who had sat in judgement on the king’s father or taken any part in his trial were being arrested and executed every week. Perhaps the writer thought it best to spare his readers’ sensibilities. Hanging, drawing and quartering – a traitor’s death – was a gruesome, sickening affair. Thomas read on.

Sir Montford’s body had been found in Pudding Lane two nights earlier, near the Honest Wherryman alehouse. He had been attacked from behind and his throat cut. As his pockets were empty, the coroner, Master Seymour Manners, had concluded that the motive was robbery. It was not known why Sir Montford had been alone in a dark street best known for its low taverns and bakers’ shops, but there were no witnesses and no other clues. This was the second such murder in the space of three weeks, the previous victim having been a Mr Matthew Smith, also robbed and found with his throat cut in Pudding Lane. The coroner had expressed the view that both victims died at the same hand.

Читать дальше