Sabina turned back to the window. The two halves opened outward, letting in the overheated breeze. She examined the frames top and bottom, then the sill. It was less than three feet above the ground outside.

There was a faint mark on the sill’s outer portion — a tiny scrape in the wood, she discerned upon closer inspection, neither deep nor long but fairly fresh. There were no other marks on the window casing. But when she felt along the top corner of the left-hand frame, her fingertip was lightly pricked by something caught there.

Carefully she pinched it off. It was a sliver of soft, blackened wood. When she rubbed it between thumb and forefinger, it left a thin smear. She sniffed the smear, then the splinter; both had a faint brackish odor.

She went to the writing table. The top left-hand drawer contained bond paper, some plain and some with a Great Orient Import-Export Company letterhead, plain and printed envelopes, handwriting tools. Sabina slipped the splinter into one of the plain envelopes, which she then folded and tucked into her skirt pocket.

In the top right-hand drawer were two accordion files, one filled with a jumble of notes written in a spidery backhand, the other with a sheaf of manuscript pages penned by a different, precise hand that was likely Miss Thurmond’s. Sabina flipped through the first few pages. This was the book Gordon Pettibone had been writing, a ponderous tome with a ponderous title: A Comprehensive History of China’s Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms.

Nothing in any of the other drawers captured her attention. She moved on to the shelves of books on the wall behind the table. Most were old and bound in brown and black leather, a few others in buckram. Judging by their titles, all were volumes of Far East and East Asian history, the preponderance of them concerning ancient China. All, that was, except for one tucked into a corner on an upper shelf. That one, also leather-bound, had the words HOLY BIBLE stamped in gold leaf on its backstrip.

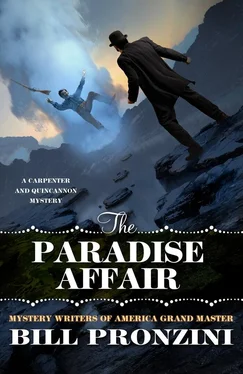

On impulse, Sabina took it down. It, too, was old and seemed to have been well read. By Pettibone’s late wife, evidently, for the flyleaf bore her signature. Tucked inside was a two-by-two-inch white index card of the sort she and John used to file addresses at Carpenter and Quincannon, Professional Detective Services. It had been in the Bible for some time, a fact attested to by a yellowish tinge to the paper and the faded ink of the single line written on one side.

RL462618359.

The penmanship was not that of the late Mrs. Pettibone, but rather the same as that on the notes in the accordion file — Gordon Pettibone’s. What did the two letters and line of numbers signify? Some sort of reference to passages of Scripture? No, that was unlikely. And nothing had been written in the Bible itself.

She decided against pocketing the index card. Instead she returned to the writing table, and with pen and ink from the drawer, copied the two letters and line of numbers onto the envelope containing the splinter.

After replacing the card and reshelving the Bible, she opened three of the Oriental history books at random. Each also contained an index card, these relatively new, on which were noted dates of purchase, prices paid, estimated worth, research references to similar volumes. The handwriting was the same as on the manuscript pages: Miss Thurmond and her cataloguing duties.

Sabina looked around the rest of the study. The fireplace, in this tropical climate, was ornamental rather than functional. There was nothing of interest on or under the armchair cushions, or under the armchairs themselves, or anywhere else in the room.

The shutter-free window drew her again. Its two halves were still open; she widened the gap and leaned out to look at the ground beneath. The stubbly grass had been cleared of most of the debris from Saturday night’s storm, but it was still littered with leaves and twigs. Needle in a haystack, she thought. Then again, perhaps not.

She closed and re-bolted the window frames, drew the drapes, and went in search of the way to the side porch.

The side porch opened off of the kitchen. Cheng showed her the way after she encountered him in the central hallway. She took the opportunity to ask that he tell Miss Thurmond she wished to speak with her and to please wait with Mr. Oakes in the parlor. The houseman, used to being given orders and to obeying them unquestioningly, went to do as she requested.

Outside, Sabina went around to the rear of the house. Starting in close to the wall, she walked slowly back and forth for a distance of several feet on either side of the shutter-free window, her body bent forward and her eyes searching the ground. When she failed to find what she sought, she moved outward by two paces and repeated the process. She had to do this five times before her efforts were rewarded.

The first object she spied and quickly picked up was an irregular chunk of light-colored wood the size of a cookie, wafer-thin along one edge, tapering gradually to a thicker, rounded outer edge. The thin portion was scraped in two places, top and bottom. She slipped the piece into her skirt pocket and continued her search.

It did not take her long to find the second chunk of wood, for it was black and of a similar shape and somewhat larger size. One of its edges, too, was thin and flattish, the surface on one side scraped and marred by a tiny gouge the size of the splinter. This piece joined the other in her pocket.

She returned to the side porch and reentered the house. Before going to the parlor, she took a few moments to compose herself. Her exertions in the fiery glare of the sun had made her feel a trifle light-headed. Prickly oozings of perspiration glazed her face and trickled on the back of her neck; her blouse felt as if it were pasted to the skin between her shoulder blades. She loosened the garment, wiped away as much of the perspiration as she could with her handkerchief. Lord, how good a cold shower would feel just now!

Earlene Thurmond was waiting in the parlor with Philip Oakes, the two of them sitting stiff-backed some distance apart and ignoring each other. Both stood when Sabina entered. The young blond woman was indeed Junoesque, broad-hipped and abundantly endowed above the waist. Her eyes were a light gray, her mouth a somewhat pinched cupid’s bow. It was impossible to tell what she was thinking as she faced Sabina; her round countenance was as unreadable as a closed book.

Oakes had a glass in one hand; the amber color identified its contents as whiskey undiluted by either water or soda. He had not had enough of it to visibly affect him. His gaze was both expectant and impatient, as were his words when he spoke.

“What took you so long? Did you find out anything?”

“I’m not sure.”

“Not sure? What do you mean, not sure?”

“Just what I said.” Sabina gave her attention to Miss Thurmond, introduced herself.

“Yes, Mr. Oakes told me your name and why you’re here.” The woman was attractive only until she opened her cupid’s-bow mouth; her voice had a thin, reedy quality that befitted a less statuesque woman. “I don’t know what I can tell you that you don’t already know.”

“Perhaps nothing. Do you mind answering a few questions?”

“Not at all.”

“Have you an opinion as to how Mr. Pettibone died?”

“It may have been an accident, as Mr. Oakes believes, or it may have been suicide. The police think it was the latter.”

“They’re wrong,” Oakes said. “Wrong!”

Sabina said, “One or the other, then. You don’t suppose it could possibly have been foul play.”

Miss Thurmond arched one of her pale eyebrows. “Foul play? Of course not. The door and windows were bolted on the inside. Mr. Oakes and I made sure of that.”

Читать дальше