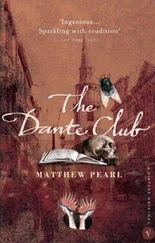

Matthew Pearl

The Dante Chamber

DOCUMENT #1: LETTER FROM OLIVER WENDELL HOLMES TO H. W. LONGFELLOW

The steamship Cephalonia, November 28, 1869

My dear Longfellow,

I have been assured that I should be kindly received in Europe, and I suppose I’d prefer anywhere on earth to this ocean liner, where a man annoys and is annoyed by the same two dozen fellow beings all day. Growing old, I realize there are few living persons left I wish to meet and few achievements to which I aspire. Instead, I have a certain longing for another sight of places I remember from travels in my youth, or places of which I read but never saw.

As for the intellectual condition of the other passengers who are not named Holmes, I should say their faces are prevailingly vacuous, their owners half hypnotized, it seems, by the monotonous throb and tremor of the great sea monster on whose back we ride. I empathize. I seem to have fewer ideas and emotions than usual.

Besides a short vacation, I have no thought of doing anything more important than brushing a little rust off and enjoying myself, while at the same time I can make my precious companion’s visit somewhat pleasanter than it would be if she went without me.

Please give Lowell, Fields, and company my warm greetings and say something witty as if I had written it. Even composing a simple letter taxes me in the rocking and swaying of my stateroom.

What book do you think I saw in the hands of one of the passengers, as I put down this letter to get fresh air above deck? Your Dante. It serves a great purpose, quite independently of its value with reference to the Florentine’s poetry. It shows our young Americans that they need not be provincial in their way of thought because of where they were born. We Boston people are so bright and wide-awake, and have been really so much in advance of our fellow barbarians, that we sometimes forget that 212 Fahrenheit is but 100 centigrade.

There is something else tugging at my brain, my dear Longfellow. I am a series of surprises to myself in the changes that years, and a specific period of darkness that I need not name, have brought about. The movement onward is like changing place in a picture gallery — the light fades from this picture and falls on that, so that you wonder where the first has gone to and see all at once the meaning of the other. What a strange thing life is! I may have believed a voyage would remove me from certain memories of — I leave that sentence unfinished. But those memories follow me with a more persistent character than before. I suppose it is terribly American to journey thousands of miles and mentally stay in America, for better or...

I reach the bottom of my page. Don’t think I expect an answer, or require consolation. I am afraid that my words as well as my handwriting betray the strain through which my nervous system is passing — but I am certain the picturesque hills of Switzerland will vanquish these thoughts, and this page will serve the world best crackling inside the hearth of your study.

In the meantime, my mood makes me wonder: what is faith? It must be a quiet belief in the existence of something not proven. Faith that is genuine enough, religionists say, may accomplish much. Might we humans possess another thing that is the opposite of faith, that is just as important or more so? Knowledge that some things seemingly immaterial — memories, fears, the fog of nightmares — are figments. When I try to leave behind my own, they take on the form of some greedy beast who, abandoned in the wild wood, transforms from tame to rabid, to hunt me down, wherever I roam. Pray as I traverse the Old World it finds some new scent to pursue!

Always faithfully yours,

Oliver Wendell Holmes

He would not be long for this world.

Hunched forward almost forty-five degrees, his body braced against the cold January wind, his big, tattered coat billowing behind. His legs trembled with each plodding step.

The coming dawn did not remove much of the gloominess these public gardens boasted at night. Strips of colored paper and beads that welcomed the New Year two weeks before were still scattered over the ground, giving the appearance of colorful strands of hair and lost teeth. Here was one of the garden squares around London that better classes shunned and appreciated. Shunned, because it was a place of blackguards and outcasts; appreciated, because these blackguards and outcasts collected on the Wapping side of the Thames kept out of the way of respectable society. When respectable persons did have a need best served in North Woolwich, they believed themselves invisible here.

Even in midwinter cold, ladies in elaborate, multicolored dresses walked along the elm-lined paths in pairs, objects of desire and subjects of contempt and fear for causing desire. Most of the girls who passed in sight of the plodder felt pity for him, though few pitied these girls. They did not know him; he was no frequenter of these gardens. One thing stood out: despite his terrible condition and his ratty clothing, the rest of him — his face plump and round, crystal blue eyes, silvering hair, smooth skin — all reeked of easier living somewhere else. Somewhere else must have been lovely.

He was like Atlas, stooped, about to lose his grip on the world.

The girls kept away, because whatever else the hunchbacked plodder might be he was in trouble that they could not afford. That explains why none came close enough to hear him utter, “God, have mercy upon me!” before his head drooped farther down. A loud crack like a whip followed.

Then he was a heap on the ground.

Another man approached at a stately pace. This man appeared somewhat rotund in his long dark coat and had a beard that extended some six inches below his chin, where it slightly cleaved in two. He lowered one knee into the rain-matted grass next to the body. Full red lips quivered from under the black bristles of his mustache. He pressed his strong fingers to his own eyes as he wept.

A crowd of the bolder girls and other onlookers began to gather. Some men hastily buttoned up vests and straightened hats. The weeping man felt their unwelcome presence. His hazel-gray eyes darted from one face to the next. He threw his hood over his head and down upon his broad brow, and began to walk away.

Another onlooker in the crowd, a shorter man with a wide, crisp mustache, trailed behind him. “ Dante ? Dante, where have you — isn’t that you?” he called after him.

Simultaneous cries of distress, meanwhile, multiplied over the crumpled-up man.

“Is the bloke dead? Look at that!”

“It’s too dark. What?”

“Don’t you see, over there? Writing: on that thing!”

A candle was secured as the sightseers closed in on the spectacle. They pointed in horror. The dead man was no hunchback, as he’d appeared from a distance. There was a massive stone that encircled his neck and back. It had put so much pressure on him that it had snapped his neck like a carrot. Someone feeling very bold — nobody remembered who, as recorded later in the reports of police interviews — reached out and touched the side of the man’s head, which wobbled on his limp neck like jelly. The crunch made by the bones as his head rolled would not be forgotten by any who heard it.

Etched into the stone that had crushed his neck were words.

Some people scrambled away from death, and others fled the police whistles that broke through the chill morning air. Those who remained tried to make out the words carved in the stone. One girl with long hair to her elbows whispered in a husky voice:

Читать дальше