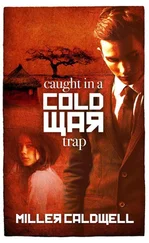

Two letters dropped on the hall carpet that morning: her passes. One must be kept safe until it was required when she returned to Britain; she was to carry the other at all times, as a guarantee that she would be allowed to travel without restriction. She wondered what travelling she might have to do in Germany.

On closer inspection, she saw that her British card was in the name of Hilda Campbell. She looked again at the German pass. Frau Hilda Richter. All was in order. She decided to telephone Eicke.

‘My passes have arrived,’ she told him.

‘Good. I meant to remind you that in Britain, of course, you must be called by your maiden name, Miss Campbell. It is a very Scottish name, I believe. Not so?’

‘Oh yes, very much so,’ she replied, smiling to herself.

‘You will soon get used to it again. Your name Frau Richter must never exist in Britain.’

‘I can’t change my name in Forres, or when I’m speaking to my mother but rest assured I won’t speak a word of German in Great Britain.’

‘You will not be posted to England or Scotland just yet.’

That surprised her. If she wasn’t to return home, where might Eicke place her?

‘Not back to Scotland?’ she queried.

‘No. For your next assignment, next month, I want you to go to school. A school for spies. You have much to learn, and time is of the essence.’

‘Next month?’

‘Yes, July third.’

‘And where is this? May I ask?

‘It is not far from Mainz. In a particularly beautiful part of Germany’

‘Mainz?’?’

‘Take the train to Mainz then the shorter journey to Baden-Baden. We’ll give you a rail pass. You will be collected from the station. Any more questions?’

‘Baden-Baden, the spa town. I have always wanted to visit there. How long will I be there? And can I tell my son?’

‘You will be there for six weeks. There will be others there too. At the end of that period, you return to Hamburg, and I shall arrange for Otto to have some leave so he can spend some time with you. I will ensure you will receive his letters. Nevertheless, your movements are secret. You cannot tell Otto anything about Baden-Baden. You can only say you are on State business. Understand?’

‘Yes, of course.’

‘In difficult times, we have to make sacrifices.’

She knew difficult times meant war.

‘So I make my way there on the third?’

‘Yes. Your bank account has been funded for that period, and you will be catered for and given the use of a launderer and cook, you understand?’

‘Then I look forward to the training.’

July 3 rdwas not long in coming. She spent some time cleaning the house, not knowing when she would return, and she wrote a lengthy letter to her mother about how busy she was, of course without saying what she would be doing.

On the day she was scheduled to go to Mainz, she was awake at dawn. The sun shone brightly, and trees left shadows on the pavements. Swallows could be seen darting with effortless ease around the city sky on the lookout for insects, finally taking shelter in their natural habitat under eves and in guttering. Hilda considered she was at last ready to travel.

The railway station at the Hamburg Hauptbahnhof was busy. Numerous naval personnel made their way to submarines and battleships at ports along the north coast. Soldiers with different shoulder flashes consulted the overhead destination boards, and debonair Luftwaffe officers seemed aloof, probably longing for the day when they could take to the skies. The multitude of uniforms was strangely comforting. She felt that the troops were confident and prepared for what would soon happen. Other people in the station looked more forbidding, and it was not too long before an official approached her.

‘Madam, your ticket please,’ he said, holding out his hand.

She showed him the travel voucher she had been given.

‘Where are you travelling to?’

‘Baden-Baden is my destination.’

‘What business do you have there?’

She took out her new pass and held it out to him.

He hesitated for a moment, then his manner changed; suddenly he was all politeness. ‘Very well, madam, have a safe journey.’

She breathed a sigh of relief and slalomed her way through other passengers to platform four.

Out of the corner of her eye, she caught sight of a commotion. Three men in trilby hats, with pistols drawn, were attempting to detain a family set to travel. The father protested loudly but no one came to his aid. Many just watched as plain-clothes police officers came to assist in the family’s detention; moments later, they were dragged off the concourse and out of sight, then order reigned again as if nothing had happened.

‘Jews,’ a man sneered. ‘They would have been caught at the port of embarkation anyway.’

Eicke’s men, Hilda thought.

The change at Mainz was straightforward; there were fewer men in military attire, but perhaps there were even more secret police eyeing every passenger, especially anyone who was nervous or tense. The age of the traveller was another factor, and Hilda wondered if she attracted less attention because of her years. Perhaps if she let some longer strands of grey hair drop from under her hat, she might just gain a little more respect.

In the train from Mainz her seat was by the window. She pulled up the leather strap and lowered the window slightly to feel fresh air. Looking round at her companions, she saw no one objected, though everyone did seem a little suspicious of everyone else. She avoided getting into conversation lest anyone asked unwelcome questions.

The train set off and she gazed out of the window. Soon the industrial landscape was behind her and green fields flew by. How nonchalant the cows were, ignorant of the way the country was heading. Hens and chicken scurried as the train approached their fences. Laundry danced in the breeze, and an occasional horse-drawn milk carriage seemed to be stationary as they sped by. Inside the carriage Hilda relaxed, but she wondered if she would ever reach British shores again, now that she had, in all appearances, tied her colours to the German mast. She knew the next few weeks would bring lots more training, and that it was crucial to keep her Scottishness under wraps.

She realised the elderly man sitting opposite her had spoken.

‘I said are you visiting family?’ he asked again.

‘No, I’m on business.’

‘I see.’

‘And you?’ she asked, partly to distract him from questioning her further.

‘I am visiting my granddaughter, Elise. Her father is away in the army and her mother has her hands full. I thought I’d come and assist.’

She smiled. Some people still had an ordinary domestic life. She could see him reading to his grandchildren on his knees when he arrived there. ‘I am sure you will be made very welcome.’

‘And you have family?’ he asked.

‘Yes, a son. My husband died.’

‘My condolences. He will avoid the troubles.’

‘The troubles?’ she asked feigning concern.

‘You don’t think there will be a war?’ he asked.

‘It is looking like it will be soon,’ she replied.

This man clearly wanted to talk, but she was already finding it a strain. She turned away and looked out of the window. It was late afternoon. The sun still shone brightly but it was sinking low, while the air was warm and clear. She closed her eyes but she could not sleep.

At Baden-Baden she gathered her suitcase and belongings and stood on the platform.

A uniformed army soldier appeared before her. ‘Frau Richter?’

She smiled at him as he took her bags and she sat in the back of his car.

The journey was comfortable until they reached a minor road. After three miles of bumping up and down, the uneven track eventually led to a series of huts amid the lush countryside and the car came to a halt. He told her to disembark. So this was to be her accommodation for the next few weeks. Her heart sank, but she was determined not to let it get her down.

Читать дальше