“You do not deny, either, that you killed my servant Matthew in London in March?”

Here he affected an air of puzzlement once more. “You lose me again, sir. Who is Matthew?”

My face must have shown the full coldness of my anger, as he looked disconcerted for the first time.

“You know perfectly well who Matthew is. The lad you so generously took under your wing in the Low Countries. The one you took to your feast and debauched. The one you met again in London and murdered so cold-bloodedly, when all he ever wanted from you was friendship and love.”

Cola’s flippant air had now evaporated, and he twisted and turned like a fish to avoid confronting what even he knew was his duplicity and cowardice.

“I remember a young lad in the Hague,” he said, “although his name was not Matthew, or so he told me. The outrageous charge of debauchery I will not even dignify with an answer, for I know not where it originates. As for murder, I merely deny it. I admit that I was set upon by a cutpurse shortly after I arrived in London. I admit I defended myself as best I could, and ran off the moment I could. The identity of my assailant, and his condition when we parted company, I cannot vouch for although I did not think him so badly injured. If someone died, I am sorry for it. If it was this boy, I am sorry for that as well, although I certainly did not recognize him and would not have hurt him if I had, however much he had deceived me. But I would advise you, in future, to pick your servants with more care and not give employment to people who supplement their wages with nighttime thievery.”

The cruelty of this statement cut through me like Cola’s sword cut Matthew’s throat, and I wished at that moment I had a knife of my own, or more freedom to act, or a soul which could encompass taking the life of another. But Cola knew full well that I was under constraint; he must have sensed it the moment I arrived, and he used his knowledge to bait and torment me.

“Be very careful what you say, sir,” I said, barely controlling my voice. “I can do you great harm if I wish.”

It was, for the time being, an empty threat, and he must have sensed it also, for he laughed easily and with contempt. “You will do what your masters tell you to do, doctor. As do we all.”

I draw now to an end; all else I heard of at second hand, or saw as an observer, and I do not presume to comment at length on matters better left to others. I was, however, on the quay the next day when Cola was brought to the boat. I watched the carriage roll up and saw the Italian, with a carefree spring in his step, march down the gangplank onto the deck. He even saw me, and smiled, and bowed ironically in my direction before disappearing below. I did not wait to see the boat get under way, but took a carriage back to my house, and left for Oxford only after I had heard from the captain of the vessel himself that Cola, and his luggage, had been tipped into the water some fifteen miles away from the shore and in such heavy weather that he could not have survived for long. Even though my revenge was complete, it brought me little satisfaction and it took many months before anything of my old calm returned. My happiness never did. Eventually Mr. Bennet, now Lord Arlington, insisted on my services again; my reluctance and distaste proved no defense against his desires. In the months in between much had happened. The alliance of Clarendon’s and Bennet’s interests held long enough for both to accomplish their aims. Faced with the destruction of his plan of murder, the open rumor that in due course Lord Clarendon’s daughter would sit on the throne of England, and the constant harassment of his people, Bristol hazarded all and tried to impeach the chancellor of treason in Parliament. It excited nothing but ridicule and contempt, and Bennet dissociated himself from the move; what assurances of support he had given Bristol in advance to tempt him into action I do not know. His Majesty was so offended by the attempt to force the removal of his minister that he exiled Bristol to the continent. Clarendon’s position was strengthened, and Bennet received his reward by adopting as his own many of Bristol’s family. More importantly, the prospect of a Spanish alliance received a mortal blow and was never mooted again.

The understanding between the two men could not last long; both of them knew that, and all the world knows how it ended. Lord Clarendon, as good a servant as a king ever had, was eventually forced into exile himself, confronting from his poverty in France the ingratitude of his king, the cruelty of his comrades, and the open avowal of Catholicism by his daughter. Bennet rose to take his place and ultimately he too fell from power, toppled by another, as he had toppled Clarendon. Such is politics, and such are politicians.

But for a while at least my efforts safeguarded the kingdom; the discontented, though well funded from Spain, could achieve nothing when faced by a government undistracted by division. I am still constantly aware, so many years later, of the terrible cost of this triumph.

All was caused by my desire to punish the man who had brought me such sorrow. And now I discover that this man, whom I hated as much as I loved Matthew, eluded my grasp and escaped my wrath. I performed ignoble deeds and even so was frustrated of my revenge. I know in my heart that I was betrayed, as the captain of that vessel who told me plain he had seen Cola drown would not have dared lie to me unless he was frightened of another more powerful still.

But I do not know who took these decisions to spare Cola and hide it from me, nor yet why they were taken. Nor do I have much chance now of discovering—Thurloe, Bristol, Clarendon, they are all dead; Bennet sulks in his gloomy retirement and talks to no man. Lower and Prestcott manifestly do not know, and I cannot imagine Mr. Cola will deign to enlighten me. The only person I have not talked to is that man Wood, but I am certain he knows little except scraps and details of no significance.

I have never disguised what I have done, though I have never advertised my deeds either. I would not have done so now, but for the arrival of this manuscript. What I have done, I own. At least events proved me correct in all substance. Even those who would criticize me must take this into account—had I not acted, Clarendon would have died and the country might well have been consumed once more. That fact, and that alone, more than justifies all I did, the injuries I suffered and those which I imposed on others.

And yet, though I know this to be true, the memory of that girl has begun to haunt me. It was a sin to wash my hands of her and stay quiet while she was condemned to death. I have known it always but never accepted it before now. I was tricked by Thurloe into that dreadful deed, and was motivated solely by my desire for justice and always thought this excuse enough.

All is known to the highest Judge of all and to Him I must entrust my soul, knowing that I have served Him to the best of my ability in all my acts.

But often now, late at night when I lie sleepless in my bed once more, or when I am deep in the frustration of prayers which no longer come, I fear my only hope of salvation is that His mercy will prove greater than was mine.

I no longer believe it will.

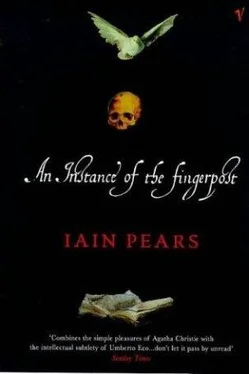

An Instance of the Fingerpost

When in a Search of any Nature the Understanding stands suspended, then Instances of the Fingerpost shew the true and inviolable Way in which the Question is to be decided. These Instances afford great Light, so that the Course of the Investigation will sometimes be terminated by them. Sometimes, indeed, these Instances are found amongst that I Evidence already set down.

Читать дальше