Steven Saylor - Catilina's riddle

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Steven Saylor - Catilina's riddle» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Catilina's riddle

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Catilina's riddle: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Catilina's riddle»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Catilina's riddle — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Catilina's riddle», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

'So you don't want land reform, you don't like Catilina—'

'I despise him! He and his circle of pampered, well-born, irresponsible dilettantes. They've had their chance to lead decent lives and they've wasted themselves instead — going hopelessly into debt to more responsible and upright citizens. This whole radical scheme of his to forgive debts is no favour to the masses — it's a way to get himself and his friends off the hook, and to plunder the property of those who deserve to keep what they and their ancestors have accumulated. If schemers like Catilina end up powerless and impoverished, it's no more than they deserve. And if the voters of Rome have no more sense than to go along with their crazy ideas—'

'All right, all right, far be it from me to stand up for Catilina. But you seem to have just as low an opinion of Caesar—'

'Who is just as much in debt! No wonder they both suck up to the famous millionaire. Catilina and Caesar are like twin babies hanging off Crassus's teats. Ha! Like Romulus and Remus suckling the she-wolf!' The speaker made obscene popping noises with his lips.

This last elicited equal parts of laughter and hissing from the crowd, who were either amused or offended by such blasphemy.

'Very well, citizen, you insult Catilina, you insult Caesar and Crassus — I suppose you cling to Pompey.'

'I have no use for Pompey either. They're all wild horses trying to break from the chariot. They're in a race with each other, and they care nothing at all for the common good.'

'And Cicero does?' sneered the orator.

'Yes, Cicero does. Catilina, Caesar, Crassus, Pompey — every one of them would make himself dictator if he could, and cut off the heads of the rest. You can't say that about a man like Cicero. He's spoken against tyranny since the dictatorship of Sulla, when it took a brave man to do so. A mouthpiece, you call him — very well, that's what a consul should be, speaking out for those in the Senate whose families made the Republic what it is and have been running it ever since the kings were thrown down. We don't need rule by the mob, or rule by dictators, but the steady, slow, sure rule of those who know best.'

This last set off a round of jeering from some newcomers who had just arrived in the crowd, and the debate degenerated into a shouting match. Fortunately, the agitation in the crowd provided an opening, and we were able to press on. A moment later Meto drew beside me with an earnest look on his face.

'Papa, I couldn't follow their argument at all!'

'I could, but only barely. Land reform! The populists all promise it, but they can't make it come true. The Optimates turn it into a dirty word.'

'What was the Rullan bill they were talking about?'

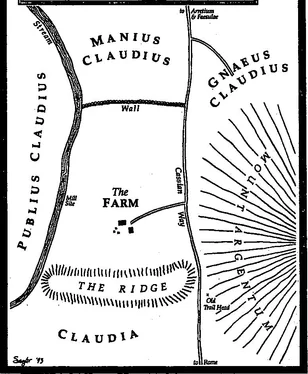

'Something that was proposed earlier this year. I remember our neighbour Claudia railing against it. I really don't know the details,' I admitted.

Rufus turned towards us. 'One of Caesar's ideas, in conjunction with Crassus, and typically brilliant. The problem: how to find land for those who need it here in Italy. The solution: sell public lands we've conquered in distant countries and set aside those proceeds to buy land in Italy on which to settle the poor in agricultural colonies. Not a wholesale confiscation and redistribution of land from rich to poor, as Catilina proposes, but the expenditure of public funds to effect a fair reapportionment.'

'Why did the man bring up Egypt?' said Meto.

"The foreign lands to be sold include those in Egypt, which the late

Alexander II bequeathed to Rome. The Rullan law proposed setting up a special commission of ten men who would oversee the project, including its administration in Egypt—'

'And Caesar would have been one of the commissioners,' said Mummius dryly, joining the discussion. 'He'd have picked Egypt like a fig from a tree.'

'If you like,' Rufus conceded. 'Crassus would have been on the commission as well, since his support was vital With Egypt under their sway, they'd have had a bastion against Pompey's power in the East, you see. You'd have thought the Optimates would like that, since they fear Pompey, too. But as long as Pompey is away from Rome and campaigning in the East, the Optimates fear Caesar and Crassus more.'

'Not to mention Catilina and the mob,' I said.

'Yes, but Catilina intentionally distanced himself from the Rullan bill. Too mild for him; to have been seen as a force behind it would have compromised his radical reputation. Nor would his support have been an asset to the bill; his enthusiasm would have further alarmed the Optimates, who were already suspicious of the idea.'

'Even so, I imagine Catilina would have accepted an appointment as one of the new land commissioners, along with Caesar and Crassus.'

Rufus smiled wryly. 'Your grasp of politics is more subtle than you let on, Gordianus.'

'But the bill was defeated,' said Meto.

'Yes. The Optimates saw it as merely a tool for Caesar and Crassus, and yes, perhaps Catilina, to increase their power, and any talk of land reform immediately sets them on edge. They always pretend to support the idea in the abstract, but no concrete proposal ever satisfies them. Cicero became their spokesman, as he has been since they rallied to support himfor the consulship. But he didn't limit himself to debating the matter in the Senate. He came here, to the Forum, and brought the issue directly to the people.'

'But it's the sort of bill the people like, isn't it? That's why they call Caesar a populist, isn't it?' asked Meto. 'Why would Cicero debate against the bill before the very people it's meant to help?'

'Because Cicero could talk a condemned man into chopping off his own head,' said Rufus. 'He knows how to make a speech; he knows what arguments will impress the mob. First, he said that the law was directed against Pompey, even though Pompey was specifically excluded from the investigations that were to be made into the acquisitions of other generals abroad. The people don't like it when they hear that something will hurt Pompey. Pompey is the darling of the mob; successful generals always are. To denigrate Pompey is to denigrate the people of Rome, to call Pompey into question is to insult Rome's favourite son, et cetera, et cetera. Then Cicero took aim at the commission itself, saying it would become a little court of ten despots. They would embezzle the funds they raised, robbing the Roman people of their own wealth; they would punish their enemies by forcing them to sell their lands, which would be almost as wicked as the proscriptions and confiscations that Sulla carried out; they would forcibly move the contented urban poor onto barren tracts of land where they would starve. Well, you know how persuasive Cicero can be, especially when it comes to convincing people to work against their own interests. I do believe he could convince a beggar that a rock is better than a coin because it weighs more, and an empty stomach is better than a full one because it causes no indigestion.'

'But Rullus must have defended the law,' said Meto.

‘Yes, and Rullus was pounded into dust — rhetorically speaking. Caesar and Crassus each wet a finger, held it in the wind, and decided to keep quiet, though in debate either one is a match for Cicero, at least to my ear. The time was simply not right, and the law was dropped. Soon people got distracted by other matters, like the incident in the theatre, and Catilina's new campaign for consul.'

'You say the time was not right for such reform,' I said. 'In Rome, and with the Optimates in control of the Senate, when is it ever the right time for change?'

'Nunquam,' said Rufus, smiling ruefully: never.

Our destination was the summit of the Capitoline Hill, where Rufus would perform his augury. We at last managed to cross the densely crowded area in front of the Rostra and came to the wide, paved path that ascends in winding stages to the summit of the Capitoline. Here we had to pause again, for a large group of men was descending the path, so many in number that they blocked any opportunity to ascend. As the group drew nearer, Rufus's face brightened. His eyes were better than mine, for he had already made out the faces of the two men who walked side by side at the head of their respective retinues. One was dressed in a senatorial toga, white bordered with purple; the other wore a toga with the much broader purple border of the Pontifex Maximus.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Catilina's riddle»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Catilina's riddle» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Catilina's riddle» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.