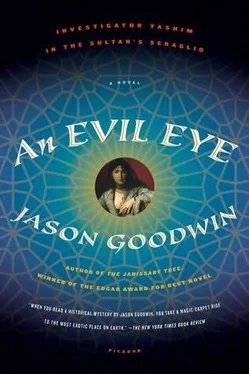

Jason Goodwin - An Evil eye

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Jason Goodwin - An Evil eye» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:An Evil eye

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

An Evil eye: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «An Evil eye»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

An Evil eye — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «An Evil eye», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Not Inalcik,” he added. Inalcik was young, courteous, and French-trained; he was always consulted by the ladies of Besiktas. “You must ask for Sabbatai Sevi. Do you understand? The old Jew.”

“Sevi the Jew.” The halberdier bowed.

But it was young Inalcik who came, smooth and serious in a black frock coat, stepping very precisely over the old stones of the courtyard with his bag in his hand.

He went into the valide’s chamber and remained there for twenty minutes, listening to her chest through a stethoscope, examining her eyelids, writing notes in a yellow book with a fountain pen.

When he emerged he looked solemn. They met Sevi at the gate to the harem. He wore a long coat, edged with velvet, and a blue skullcap. Dr. Inalcik looked surprised, and amused.

“A second opinion, Dr. Sevi. I approve, heartily.” His eyes twinkled as he outlined his own diagnosis to the Jew, who stooped to listen. “I hope you will be able to do more than I have achieved,” he added.

Sevi opened his hands. “I am very old, doctor. So is the lady.”

As Yashim led him to the valide’s room, Sevi stayed him with his hand. “The mind?”

“Wandering,” Yashim explained. “It has been like this for-” He screwed up his eyes, casting back. “A month, maybe more. Now, I think, she spends more time at home-her childhood home.”

Sevi nodded. “Perhaps she had a very happy childhood. Can she walk?”

“I haven’t seen her walk in weeks.”

“Then why not a visit to her childhood home? It’s easier on the feet.”

He came without a bag, or instruments of any kind. He knelt by the divan and took the valide’s hand in his own. After a while he peered more closely at her fingers.

Yashim felt a twinge of doubt. In Sevi’s day, the doctor often examined a woman through a curtain. Childbirth, disease, all manner of conditions had to be treated by the doctor without actually touching, or even inspecting, the woman’s body; it was the tradition, it maintained propriety.

“Modern medicine,” Inalcik had remarked, as he clipped open his bag and retrieved his stethoscope, “goes rather deeper to the sources and the causes of discomfort and illness.”

The old Jew remained on his knees for some time, watching the valide’s face, absently rubbing her hand in his.

He seemed to have gone into some sort of dream. Yashim gave a discreet cough and the old man sighed.

He unfolded slowly, and stood up.

“Poison?” Yashim asked.

Sabbatai Sevi looked at him sadly. “Poison? No. The valide sultan,” he added gravely, “is extremely thirsty.”

113

Roxelana dreamed. She dreamed she was all dressed up like a big bear. Furry boots. Furry hat.

“You must catch it this time, silly!”

“I will try, my precious!” The kalfa smiles at the little girl. But it is hard to catch a ball made of snow when the light is beginning to fade.

Roxelana knows this. It is what makes her laugh.

She says: “You may sit in the arbor. I am going to play.” When the kalfa crouches down to put a shawl around her, Roxelana tells her about the bear. The kalfa is Elif.

The kalfa laughs, smoothing her hair, but her eyes go out toward the garden.

Roxelana runs to the tree, taking big steps in the snow, like a bear. She is a bear and can hide behind the thick black trunk. There is not as much snow on the ground here.

Peep-o! Her kalfa is Melda now, sitting in the arbor, on the stone seat where they have put the cushions. Peep-o!

Silly Melda! She is not looking. She doesn’t know there is a bear so close.

She glances around. The trees at the end of the harem garden are tangled, and black and white with snow, and the snow between is quite fresh and smooth. She sets off, planting her fur boots into the white coverlet one after the other. Counting. Melda cannot see her; the tree is between them.

One step, two step, three step, four.

The trees are close. She can see between them now, into the shadows. For a bear those shadows would be a good hiding place.

Roxelana stops. She turns her head and looks back with a dubious frown. Of course she cannot see her kalfa, because of the big tree. What she can see are her footprints in the snow, and for a moment she wonders how they got there, those footprints coming after her across the shrouded lawn. They have swerved from the big tree and chased after her, dark sockets running across the whiteness. They are headed right toward her. To where she is standing.

And before she can turn her head she knows that the bear is on the other side, in the shadows behind her. The little girl opens her mouth to scream, but nothing comes out.

She hears the kalfa calling, and sees herself running back toward the big tree, running too slowly, willing her face forward, with the footprints always just a step behind her.

She woke up, gasping, wide-eyed in the dark.

The quilt had slipped onto the floor: it made a shape in the dark, and Roxelana was cold and afraid and all alone.

114

In snow, Istanbul transformed itself from a city of half a million people into a fantastic forest running down to an icy shore: its domes were the earthworks of a vanished race of giants, its minarets gaunt boles of shattered trees, its roofs, blanketed under a rippling veneer of snow, terraced fields marked only by the arrowed tracks of birds and the dimpled pawprints of hungry cats. The rattle of porters’ barrows, the clatter of hooves, the usual hum of markets and muezzins and street hawkers were muffled. Some lanes were blocked; now and then great slides of snow would precipitate themselves from the roofs and land with a whump! on the street below.

Yashim glimpsed lamplight as he reached the water steps at Balat. He had left the valide in the care of two elderly eunuchs, who were to give her sips of lukewarm water whenever she awoke. Tulin had retired to the girls’ dormitory, taking her instrument with her. He had gone back down the stairs with the sound of Tulin’s flute blowing in his ears.

She played beautifully. She played, perhaps, as a consolation. But the music had needled him.

Lanterns hung from the mooring poles; two caiquejees were keeping warm by knocking ice from the base of the poles with the ends of their oars. Yashim had heard that the Golden Horn might freeze.

He stamped his feet and one of the caiquejees grabbed a lantern and swung it up.

“Fare, efendi?”

“Pera stairs,” he said. “How’s the ice?”

The man blew out his cheeks. He reached down into his caique and scattered the cushions, which had been piled up beneath a tarpaulin. “If it gets any thicker, I’ll carry you on my back,” he said cheerfully. “At your pleasure, efendi.”

The boatman picked up the oars and with a deft flick of his arm sent the fragile craft racing into the deep, still waters of the Golden Horn. Overhead a few stars shone among the drifting clouds, and on either bank the snow showed pale against the hills. Something was alive in the back of Yashim’s mind; something that wanted to be remembered, but lurked there, shy of the glare of his thoughts as if it feared the eye.

The boatman set him down opposite the steps that climbed the hill to the Galata Tower. Yashim was relieved to find that they had been swept and even scattered with ashes. His breath cooled on his cheeks as he climbed, pausing now and then to admire the snowy hills of Istanbul. A dog, whimpering on its cold paws, slunk past in the shadows. Yashim skirted the shacks that had spilled out around the base of the tower, and pressed on up a sloping street to the Grande Rue.

At the Polish residency, someone-Marta, perhaps-had scraped a path across the frozen carriage sweep to the front steps. As he slithered on the ice, Yashim wondered if it might have been better to leave the snow.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «An Evil eye»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «An Evil eye» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «An Evil eye» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.