Later, as they walked home, with Emily far in front chattering away with a neighbour’s girl, Mary said,

‘I saw Sarah Rains at the market yesterday.’

He recalled her, the woman who ran the Dame school where his daughters had been educated. ‘How is she?’ he asked.

‘She was telling me that she knows a good family in Headingley that needs a governess for their girls. She thought Emily would be ideal.’

‘Emily?’ he burst out in astonishment. His wayward girl with ambitions as a writer working as a governess?

‘She’s grown up a lot since. . in the last few months, Richard. She’s clever. And she needs something to do with her life.’

‘Have you talked to her about it?’

Mary nodded. ‘She wants the position.’

‘And Mrs Rains vouches for the family?’

‘Yes. I told Emily it was up to you.’

‘I’d want to know more about these people first.’

Mary smiled gently. ‘I suspected that.’

‘But if everything’s fine, I don’t see why not. It could be exactly what she needs.’

On Monday morning there was crisp birdsong in the air and the smell of summer in the wind. Nottingham arrived at the jail with early light. He’d barely settled to his desk when Sedgwick arrived at a run, his face an awkward confusion of disbelief and joy.

‘You won’t believe this, boss.’

The Constable waited, wondering.

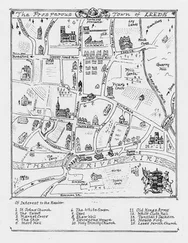

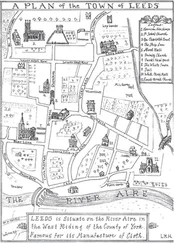

‘The night men found the Hendersons in the Aire. They’d drowned.’

‘What, both of them?’

‘Aye, the pair together. They’d fetched up by the bridge, in just their shirts. Their clothes were upstream. Looks like they’d got drunk and gone swimming. The lads said they’d had two complaints about them being rowdy in the inns last night.’

Nottingham shook his head in surprise and pleasure. ‘God works in mysterious ways, eh, John?’

‘I thought you’d be pleased, boss.’ The deputy was grinning. ‘The coroner’s been down and I’m just waiting on some more men to bring the bodies back here. I had to come and tell you.’

‘No need to be too gentle with them.’

‘I wasn’t planning on it.’

He ducked out, going back to his work. For a few minutes the Constable thought about the brothers. Once again he’d been spared the need to act. Slowly he picked up the quill, sharpening the nib with a small knife, and started on his reports.

He’d been scribbling for a while when the door opened and Josh arrived, accompanied by David Petulengro. The lad looked healthy, his face shining, but he was hesitant, setting foot in the jail as if it was a place that scared him. The Constable smiled.

‘You’ve come to say your farewells, haven’t you, lad?’ Nottingham asked.

Josh was taken aback, eyes widening. ‘How did you know, boss?’

‘Don’t you remember? I know everything.’ He laughed. ‘You should have learnt that by now. No,’ he continued, ‘I’ve seen it in you for a while now when I’ve been up at the camp. You’re due some happiness.’

‘I couldn’t go without seeing you, boss. I needed to thank you,’ Josh said simply. ‘For everything.’

The Constable nodded. ‘Have you seen Mr Sedgwick yet?’

‘I visited him and Lizzie last night.’

‘Did he ask you to stay on here?’

‘Yes,’ the boy admitted.

‘Well, for what it’s worth, I think you’re doing the right thing. The best thing. Get away from Leeds. But,’ he added, ‘if you change your mind, I’ve always got a job for you.’

Josh smiled and blushed deep.

‘Where will you go?’

‘We go to the horse fair at Shipley,’ Petulengro interjected. ‘Then up to big gathering in Appleby. You know it?’

Nottingham shook his head. The Gypsy smiled. ‘All Gypsy horses. Big fair. But we come back next winter.’

The Constable smiled. ‘You always do. And bring this one with you. I want to see him again.’

Reaching across the desk, the two men clasped hands.

The door swung wide and men carried in the corpses of Peter and Paul Henderson, their bodies hardly concealed under old, thin sheets. Petulengro looked pointedly at Nottingham. ‘We leave this morning. We just had to finish few things first.’

Nottingham raised his hand as the Gypsy walked out.