“There was… nothing I could do,” the midwife said softly. “The fever was too strong. We took her-”

“No!”

Kuisl pushed Martha aside and staggered into the room. At the large, battered table beneath the crucifix in the corner sat his family, their vacant eyes still puffy from crying. At the center of the table stood a large bowl of steaming porridge, untouched. The hangman saw Barbara and Georg-the latter having grown a light fuzz on his upper lip-and he saw Magdalena and Simon holding Peter and Paul on their laps. The boys were sucking their thumbs in unusual silence.

They were all there except his wife, Anna-Maria. The worn stool she’d always sat on-where she’d groused, hugged, darned socks, and sung songs-was empty.

Kuisl felt a pang in his heart as painful as if he’d been run through with a sword in battle.

It can’t be. Oh, great God, if you really exist, tell me this isn’t true. It’s an evil prank. I pray to you, and you slap me in the face…

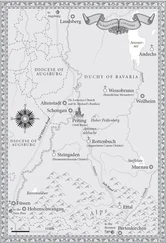

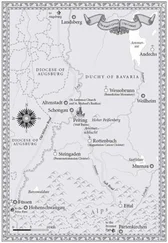

“It happened just yesterday,” Magdalena whispered in a low voice. “This plague cost many in Schongau their lives, and she was one of the last.”

“I… I should have stayed here. I could have helped her.” His broad shoulders slumped. Suddenly he looked very old.

“Nonsense, Father,” said Magdalena, shaking her head vigorously. “Don’t you think Martha tried everything? God gives us life, and he takes it away. Death was just too strong. All we can do is pray…” She stopped short, tears running down her face as Simon squeezed her hand.

“Would you like to see her?” the medicus asked his father-in-law gently. “She’s in the other room.”

Kuisl nodded, then turned away silently and moved into the next room. No one followed him.

As if she were just sleeping, Anna-Maria lay with closed eyes in the large bed they’d shared for so long. Her hair was still long and black, with only a few strains of gray. Someone had combed her hair and dressed her in a white lace nightshirt. A few flies buzzed through the room, alighting on her waxen face, and Kuisl brushed them away. Then he knelt beside the bed and took his wife’s hand.

“My Anna,” he murmured, gently stroking her cheeks. “What am I to do now that you’re no longer here? Who’s going to scold me when I’ve had too much to drink? Who will pray for me in the church? Who…” He stopped short and bit his lip. They’d been married more than thirty years. As a mercenary, he’d brought Anna back from one of the wars, and together they’d grown old. Tears ran down his scarred face-the first tears in many, many years.

He couldn’t help thinking again about what the mad woman in the Kien Valley had told him a week ago.

Repent, hangman! Soon misfortune will strike you like a bolt from the blue.

Was this the misfortune that would strike him? Was this the punishment for all the dead who had paved his way through life? Could God be so gruesome?

He heard a faint sound from the neighboring room. Magdalena had come in behind him and placed her hand on his shoulder.

“I… must tell you something,” she began hesitantly. “I don’t know if this is the right moment, but I’m sure Mother would have wanted it this way.”

Kuisl remained silent, only his raised head revealing that he was listening.

“It’s just…” Magdalena started to say. “Well… Peter and Paul will soon be sharing the little room upstairs with someone. I’m… I’m going to have another child.”

The hangman didn’t respond, but Magdalena could sense his mighty frame begin to tremble.

“Martha examined me, and she’s quite sure,” she said with a smile. “I was feeling ill a few days ago, do you remember? And now we know why I was constantly nauseated.”

Now that she’d broken the news, words poured out like a warm summer rain.

“And this time, Martha thinks it will be a girl,” she continued. “What do you think? Would you like to have a little granddaughter?”

Kuisl snorted. It seemed to Magdalena he couldn’t decide whether to laugh or cry.

“As if one of you wasn’t enough,” he grumbled finally.

The hangman squeezed the hand of his wife one final time, then turned and embraced Magdalena so firmly she could hardly breathe.