Ken Follett

Night Over Water

To my sister Hannah, with love

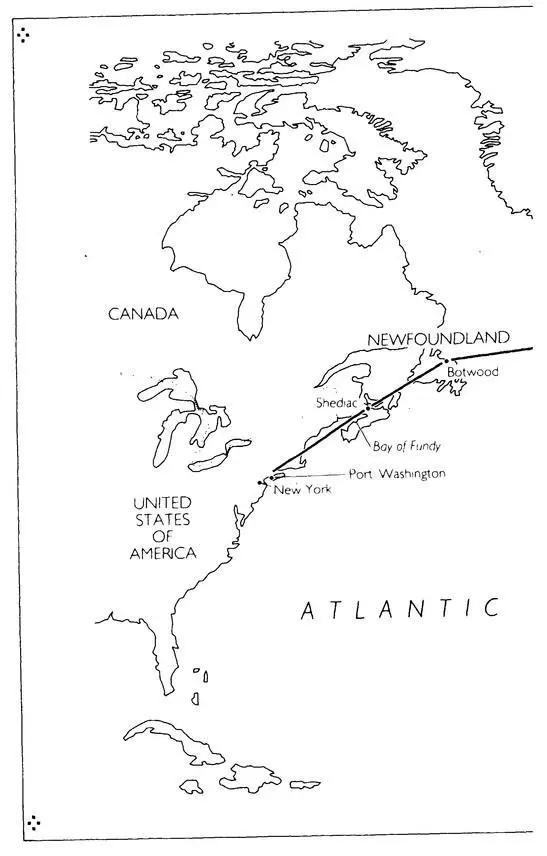

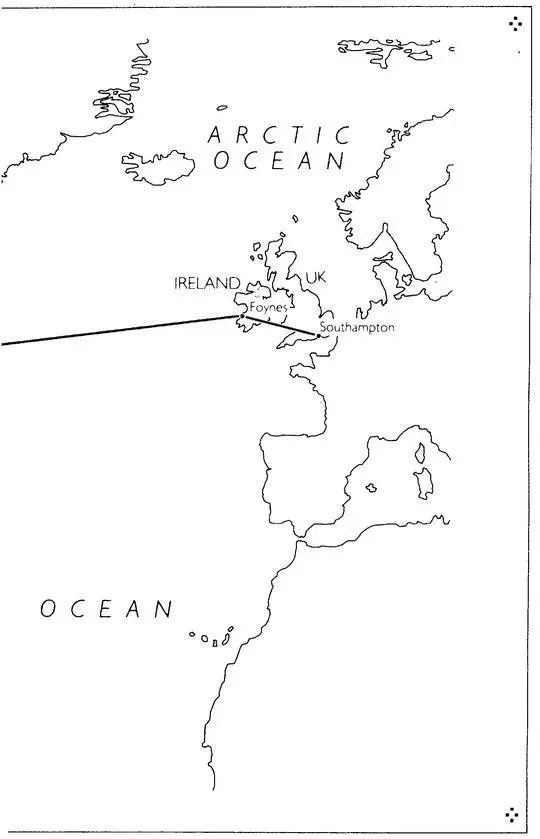

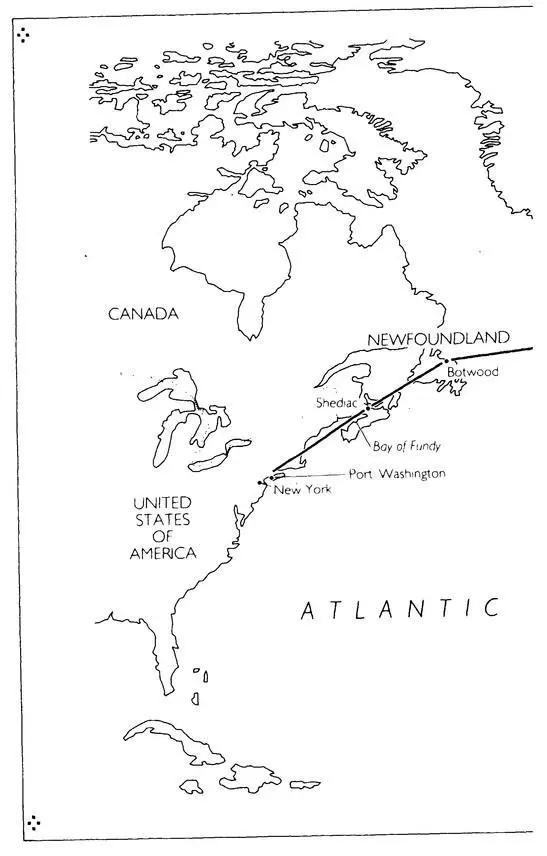

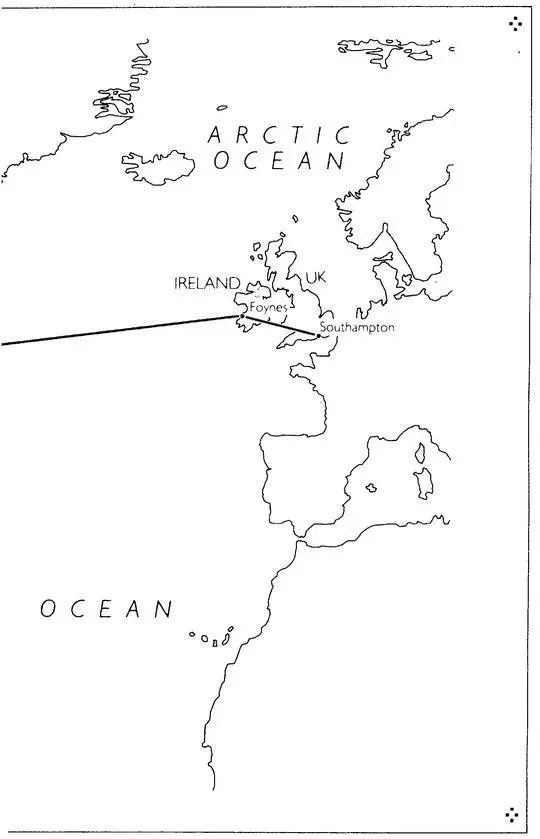

The first air passenger service between the U.S.A. and Europe was started by Pan American in the summer of 1939. It lasted only a few weeks; the service was curtailed when Hitler invaded Poland.

This novel is the story of an imaginary last flight, taking place a few days after war was declared. The flight, the passengers and the crew are all fictional. However, the plane itself is real.

In September 1939 a British pound was worth $4.20.

A shilling was one twentieth of a pound, or 21 cents.

A penny was one twelfth of a shilling, or about two cents.

A guinea was a pound and a shilling, or $4-41

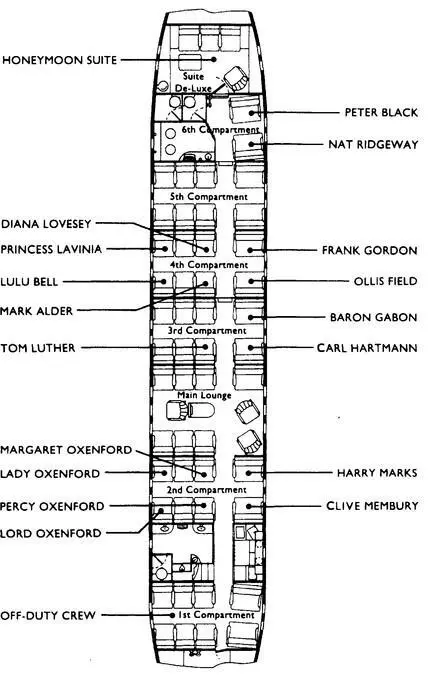

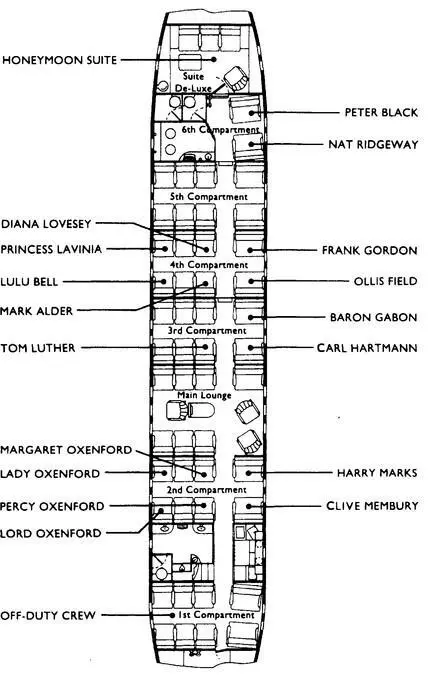

PASSENGER DECK PLAN PAN AMERICAN AIRWAYS SUPER-CLIPPERS

PLANE: BOEING 314 PASSENGERS: 74 DAY, 40 NIGHT. WING SPAN: 152 FEET HULL: 106 FT. POWER: FOUR 1500 H.P. WRIGHT CYCLONE ENGINES

Itwas the most romantic plane ever made.

Standing on the dock at Southampton, at half past twelve on the day war was declared, Tom Luther peered into the sky, waiting for the plane with a heart full of eagerness and dread. Under his breath he hummed a few bars of Beethoven over, and over again: the first movement of the Emperor Concerto, a stirring tune, appropriately warlike.

There was a crowd of sightseers around him: aircraft enthusiasts with binoculars, small boys and curiosity seekers. Luther reckoned this must be the ninth time the Pan American Clipper had landed on Southampton Water, but the novelty had not worn off. The plane was so fascinating, so enchanting, that people flocked to look at it even on the day their country went to war. Beside the same dock were two magnificent ocean liners, towering over people’s heads, but the floating hotels had lost their magic: everyone was looking at the sky.

However, while they waited they were all talking about the war, in their English accents. The children were excited by the prospect; the men spoke knowingly in low tones about tanks and artillery; the women just looked grim. Luther was an American, and he hoped his country would stay out of the war: it was none of America’s business. Besides, one thing you could say for the Nazis: they were tough on communism.

Luther was a businessman, manufacturing wool cloth, and he had had a lot of trouble with Reds in his mills at one time. He had been at their mercy: they had almost ruined him. He still felt bitter about it. His father’s menswear store had been run into the ground by Jews setting up in competition, and then Luther Woolens was threatened by the Commies—most of whom were Jews! Then Luther had met Ray Patriarca, and his life had changed. Patriarca’s people knew what to do about Communists. There were some accidents. One hothead got his hand caught in a loom. A union recruiter was killed in a hit-and-run. Two men who complained about breaches of the safety regulations got into a fight in a bar and finished up in the hospital. A woman troublemaker dropped her lawsuit against the company after her house burned down. It only took a few weeks: since then there had been no unrest. Patriarca knew what Hitler knew: the way to deal with Communists was to crush them like cockroaches. Luther stamped his foot, still humming Beethoven.

A launch put out from the Imperial Airways flying-boat dock, across the estuary at Hythe, and made several passes along the splashdown zone, checking for floating debris. An eager murmur went up from the crowd: the plane must be approaching.

The first to spot it was a small boy with large new boots. He had no binoculars, but his eleven-year-old eyesight was better than lenses. “Here it comes!” he shrilled. “Here comes the Clipper!” He pointed southwest. Everyone looked that way. At first Luther could see only a vague shape that might have been a bird but soon its outline resolved, and a buzz of excitement spread through the crowd as people told one another that the boy was right.

Everyone called it the Clipper, but technically it was a Boeing B-314. Pan American had commissioned Boeing to build a plane capable of carrying passengers across the Atlantic Ocean in total luxury, and this was the result: enormous, majestic, unbelievably powerful, an airborne palace. The airline had taken delivery of six and ordered another six. In comfort and elegance they were equal to the fabulous ocean liners that docked at Southampton, but the ships took four or five days to cross the Atlantic, whereas the Clipper could make the trip in twenty-five to thirty hours.

It looked like a winged whale, Luther thought as the plane came closer. It had a big blunt whalelike snout, a massive body and a tapering rear that culminated in twin high-mounted tailfins. The huge engines were built into the wings. Below the wings was a pair of stubby sea-wings, which served to stabilize the aircraft when it was in the water. The bottom of the plane had a sharp knife-edge like the hull of a fast ship.

Soon Luther could make out the big rectangular windows, in two irregular rows, marking the upper and lower decks. He had come to England on the Clipper exactly a week earlier, so he was familiar with its layout. The upper deck comprised the flight cabin and baggage holds and the lower was the passenger deck. Instead of seat rows, the passenger deck had a series of lounges with davenport couches. At mealtimes the main lounge became the dining room, and at night the couches were converted into beds.

Everything was done to insulate the passengers from the world and the weather outside the windows. There were thick carpets, soft lighting, velvet fabrics, soothing colors and deep upholstery. The heavy soundproofing reduced the roar of the mighty engines to a distant, reassuring hum. The captain was calmly authoritative, the crew clean-cut and smart in their Pan American uniforms, the stewards ever attentive. Every need was catered to. There were constant food and drink. Whatever you wanted appeared as if by magic, just when you wanted it: curtained bunks at bedtime, fresh strawberries at breakfast. The world outside started to appear unreal, like a film projected onto the windows; and the interior of the aircraft seemed like the whole universe.

Such comfort did not come cheap. The round-trip fare was $675, half the price of a small house. The passengers were royalty, movie stars, chairmen of large corporations and presidents of small countries.

Tom Luther was none of those things. He was rich, but he had worked hard for his money, and he would not normally have squandered it on luxury. However, he had needed to familiarize himself with the plane. He had been asked to do a dangerous job for a powerful man—very powerful indeed. He would not be paid for his work, but to be owed a favor by such a man was better than money.

The whole thing might yet be called off: Luther was waiting for a message giving him the final go-ahead. Half the time he was eager to get on with it; the other half, he hoped he would not have to do it.

Читать дальше