Mother said: “Yes—she was my mother’s mother. Why, dear, what have you found?”

Percy gave the photograph to Father and the others crowded around to look at it. It showed a street scene in an American city, probably New York, about seventy years ago. In the foreground was a Jewish man of about thirty with a black beard, dressed in rough workingman’s clothes and a hat. He stood by a handcart bearing a grinding wheel. The cart was clearly lettered with the words REUBEN FISHBEIN—GRINDER. Beside the man stood a girl, about ten years old, in a shabby cotton dress and heavy boots.

Father said: “What is this, Percy? Who are these wretched people?”

“Turn it over,” said Percy.

Father turned the picture over. On the back was written: RUTHIE GLENCARRY, NÉE FISHBEIN, AGED 10.

Margaret looked at Father. He was utterly horrified.

Percy said: “Interesting that Mother’s grandfather should marry the daughter of an itinerant Jewish knife grinder, but they say America’s like that.”

“This is impossible!” Father said, but his voice was shaky, and Margaret guessed that he thought it was all too possible.

Percy went on blithely: “Anyway, Jewishness descends through the female, so as my mother’s grandmother was Jewish, that makes me a Jew.”

Father had gone quite pale. Mother looked mystified, a slight frown creasing her brow.

Percy said: “I do hope the Germans don’t win this war. I shan’t be allowed to go to the cinema and Mother will have to sew yellow stars on all her ballgowns.”

This was sounding too good to be true. Margaret peered intently at the words written on the back of the picture, and the truth dawned. “Percy!” she said delightedly. “That’s your handwriting!”

“No, it’s not!” said Percy.

But everyone could see that it was. Margaret laughed gleefully. Percy had found this old picture of a little Jewish girl somewhere and had faked the inscription on the back to fool Father. Father had fallen for it, too, and no wonder: it must be the ultimate nightmare of every racist to find that he has mixed ancestry. Serve him right.

Father said, “Bah!” and threw the picture down on a table. Mother said, “Percy, really,” in an aggrieved voice. They might have said more, but at that moment the door opened and Bates, the bad-tempered butler, said: “Luncheon is served, your ladyship.”

They left the morning room and crossed the hall to the small dining room. There would be overdone roast beef, as always on Sundays. Mother would have a salad: she never ate cooked food, believing that the heat destroyed the goodness.

Father said grace and they sat down. Bates offered Mother the smoked salmon. Smoked, pickled or otherwise preserved foods were all right, according to her theory.

“Of course, there’s only one thing to be done,” Mother said as she helped herself from the proffered plate. She spoke in the offhand tone of one who merely draws attention to the obvious. “We must all go and live in America until this silly war is over.”

There was a moment of shocked silence.

Margaret, horrified, burst out: “No!”

Mother said: “Now I think we’ve had quite enough squabbling for one day. Please let us have lunch in peace and harmony.”

“No!” Margaret said again. She was almost speechless with outrage. “You—you can’t do this. It’s—it’s ...” She wanted to rail and storm at them, to accuse them of treason and cowardice, to shout her contempt and defiance out loud; but the words would not come, and all she could say was: “It’s not fair!”

Even that was too much. Father said: “If you can’t hold your tongue you’d better leave us.”

Margaret put her napkin to her mouth to choke down a sob, pushed her chair back and stood up, and then fled the room.

They had been planning this for months, of course.

Percy came to Margaret’s room after lunch and told her the details. The house was to be closed up, the furniture covered with dust sheets and the servants dismissed. The estate would be left in the hands of Father’s business manager, who would collect the rents. The money would pile up in the bank: it could not be sent to America because of wartime exchange control rules. The horses would be sold, the blankets moth-balled, the silver locked away.

Elizabeth, Margaret and Percy were to pack one suitcase each: the rest of their belongings would be forwarded by a removal company. Father had booked tickets for all of them on the Pan American Clipper, and they were to leave on Wednesday.

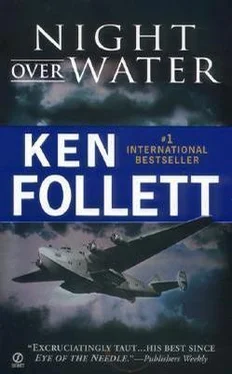

Percy was wild with excitement. He had flown once or twice before, but the Clipper was different. The plane was huge, and very luxurious: the newspapers had been full of it when the service was inaugurated just a few weeks ago. The flight to New York took twenty-nine hours, and everyone went to bed in the night over the Atlantic Ocean.

It was disgustingly appropriate, Margaret thought, that they should depart in cosseted luxury when they were leaving their countrymen to deprivation, hardship and war.

Percy left to pack his case and Margaret lay on her bed, staring at the ceiling, bitterly disappointed, boiling with rage, crying with frustration, powerless to do anything about her fate.

She stayed in her room until bedtime.

On Monday morning, while she was still in bed, Mother came to her room. Margaret sat up and gave her a hostile stare. Mother sat at the dressing table and looked at Margaret in the mirror. “Please don’t make trouble with your father over this,” she said.

Margaret realized that her mother was nervous. In other circumstances this might have caused Margaret to soften her tone; but she was too upset to sympathize. “It’s so cowardly!” she burst out.

Mother paled. “We’re not being cowardly.”

“But to run away from your country when a war begins!”

“We have no choice. We have to go.”

Margaret was mystified. “Why?”

Mother turned from the mirror and looked directly at her. “Otherwise they will put your father in prison.”

Margaret was taken completely by surprise. “How can they do that? It’s not a crime to be a Fascist.”

“They have Emergency Powers. Does it matter? A sympathizer in the Home Office warned us. Father will be arrested if he’s still in Britain at the end of the week.”

Margaret could hardly believe that they wanted to put her father in jail like a thief. She felt foolish: she had not thought about how much difference war would make to everyday life.

“But they won’t let us take any money with us,” Mother said bitterly. “So much for the British sense of fair play.”

Money was the last thing Margaret cared about right now. Her whole life was in the balance. She felt a sudden access of bravery, and she made up her mind to tell her mother the truth. Before she had time to lose her nerve, she took a deep breath and said: “Mother, I don’t want to go with you.”

Mother displayed no surprise. Perhaps she had even expected something like this. In the mild, vague tone she used when trying to avoid an argument, she said: “You have to come, dear.”

“They’re not going to put me in jail. I can live with Aunt Martha, or even cousin Catherine. Won’t you talk to Father?”

Suddenly Mother looked uncharacteristically fierce. “I gave birth to you in pain and suffering, and I’m not going to let you risk your life while I can prevent it.”

For a moment Margaret was taken aback by her mother’s naked emotion. Then she protested: “I ought to have a say in it—it’s my life!”

Mother sighed and reverted to her normal languorous manner. “It makes no difference what you and I think. Your father won’t let you stay behind, whatever we say.”

Читать дальше