‘An essay on nominalism?’ asked Michael, looking around the assembled scholars in wary disbelief. ‘Is that what this great secret is? Is that why Faricius risked life and limb to go outside when it was obvious he should have remained here?’

Horneby nodded unhappily, while the other students shook their heads in disgust that Horneby had betrayed their dead colleague’s trust.

‘Faricius was a nominalist?’ whispered Lincolne, aghast. ‘If only I had known! I could have used my powers of reason to show him that he was wrong, and that nominalism is heresy.’

‘No,’ said Horneby. ‘He was quite certain of his beliefs and he argued them convincingly. You would not have dissuaded him. We all tried and were unsuccessful.’

Michael scratched his chin, a puzzled frown creasing his fat features. ‘Nominalism is a complex theory. I cannot see that a mere novice would provide us with any new insights, and so I fail to see why this essay is important.’

‘Faricius could have provided you with new insights,’ argued Horneby. ‘He had a brilliant mind, and spent a good deal of time honing his debating skills. We were proud of him, but afraid for him at the same time.’

Bartholomew suspected that Horneby was right. Walcote, Timothy and Janius had all claimed to admire Faricius’s thinking, while the great William Heytesbury had even offered to take him as a student. A man like Heytesbury could choose any scholar he wanted, and that he was interested in Faricius was revealing. Bartholomew realised that Horneby and his cronies were not the only ones who had maintained their silence about Faricius’s beliefs: Heytesbury had also declined to enlighten Michael with what he knew of the Carmelite friar murdered at around the time he had arrived in Cambridge himself.

‘And all of you knew about Faricius’s philosophical leanings?’ asked Michael, looking around at the other students. They nodded reluctantly, casting guilty glances at each other.

‘Yes,’ said Horneby. ‘But he talked to other scholars in the University known to support nominalism, too, so that he could learn from them.’

‘Such as whom?’ demanded Michael.

‘I cannot remember precisely,’ said Horneby, a little testily. ‘Half the town believes in nominalism, so he was not exactly strapped for choice.’

‘Henry de Kyrkeby, the Dominican precentor, is due to give the University Lecture on nominalism,’ suggested another student, more helpfully. ‘I think Faricius waylaid him and discussed his ideas once. Then there is Father Paul of the Franciscans, who is a tolerant and kindly man. And I saw Faricius in deep discussion with your Junior Proctor on several occasions.’

‘Brother Timothy?’ asked Michael, regarding doubtfully the Benedictine who stood behind him. ‘You have not mentioned this before.’

‘My discussions with him were of a more general nature,’ said Timothy, surprised by the student’s assertion. ‘We did not talk about nominalism.’

‘Not Timothy, the other one. Will Walcote,’ said the student.

‘Unfortunately, Will Walcote is dead,’ said Michael. ‘I do recall him saying that he had met Faricius, however, and so I know you are telling the truth on that score. Who else?’

‘I cannot remember,’ said Horneby again. ‘It was not something he discussed with us. He knew we did not agree with his ideas, and so he tended not to tell us about them.’

‘Where is this essay now?’ demanded Lincolne, still angry. ‘And what do you think it had to do with his death?’

‘Quite,’ said Michael. ‘I am no nominalist myself, and I appreciate why many people find its tenets heretical. But I cannot see why writing about it should result in anyone’s demise.’

‘I disagree,’ said Lincolne. ‘Nominalism poses one of the greatest threats to our Church and our society since the pestilence. It causes people to question basic truths like the manner of the creation and the nature of God. It is dangerous, and I will have none of it in my friary.’

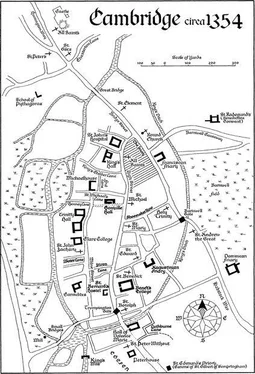

‘Because we all know you feel that way, Faricius could not keep his essay here,’ explained Horneby to his Prior. ‘He always left it in a crevice in the wall that surrounds the Church of St John Zachary. When he heard that the Dominicans were coming, he went to fetch it.’

‘Did you see this essay when you found him?’ asked Michael of Bartholomew.

The physician shook his head, but thought about Faricius’s desperation when he had learned that his scrip was missing. Bartholomew had been wrong. Faricius had not been delirious or confused about which of his scrips he had carried, and it had not been the ruby ring that he had been thinking about: his scrip must have contained his precious essay.

‘I suppose this means he was killed on his way to fetch the thing,’ surmised Michael.

Bartholomew shook his head. ‘Given his frantic desperation when he learned his scrip was missing, I think it more likely that he had collected the essay and was on his way home with it.’

‘You had better show me this hiding place in the churchyard of St John Zachary, Horneby,’ said Michael tiredly. ‘It is possible that the essay – or a copy – is still there.’

‘Lynne and I have already looked,’ said Horneby, exchanging a glance with his friends. ‘We went on Monday night – we did use the tunnel, before you ask – but it had gone. The stone had been replaced in the wall, and the branches of the nearby bush arranged to hide evidence of chipped mortar. Faricius always did that. I suppose he intended to use it again once the riot was over.’

Michael sighed. ‘What a mess! I wish you had told me all this before. It might have saved a good deal of time.’

The students hung their heads, and none would meet the eyes of their Prior, who glowered at them in silent fury. Bartholomew could not decide whether Lincolne’s anger was directed at them for keeping secrets and delaying Michael’s investigation, or whether he was merely indignant that they had helped to harbour a heretic in their midst.

So, had Faricius’s controversial essay brought about his death? Recalling his horror when he learned that his scrip had been stolen, Bartholomew was certain it had played some role. Faricius had been so concerned about its loss that he had even failed to reveal the identity of the person or people who had stabbed him. Bartholomew supposed it was possible that the killers were men Faricius had not known, although if the essay were at the heart of the matter, that seemed unlikely.

As far as the physician could see, there were two possible explanations for why Faricius had died. First, he might have been murdered by a realist, who was afraid that a clever thinker like Faricius would promote the cause of nominalism to the detriment of realism. If this were true, then it was likely that Faricius’s killer was a Carmelite. Had one of his colleagues killed him, to protect the theory that the Carmelite Order had chosen to champion? Bartholomew gazed at Horneby and his friends, and wondered whether one of them still knew more than he had told. But Horneby suggested that Faricius had talked to lots of people, including the missing Dominican Precentor, about his affinity with nominalism. Was Kyrkeby’s absence related to Faricius’s murder? Had Kyrkeby committed the crime, then fled the town? But Kyrkeby was Bartholomew’s patient, and the physician knew Kyrkeby’s weak heart would not have permitted him to engage in a violent struggle with a young and healthy man. Yet how fit did one need to be to slide a sharp knife into someone’s stomach?

The second possibility was that the killer knew an essay was in the making, but had made the assumption that it was in support of realism: because Faricius was a Carmelite, it was not unreasonable to assume that he had followed his Order’s teaching. Therefore, the suspects were the nominalists, who would not want a brilliant essay in defence of realism circulating the town. Faricius’s killer could therefore be a Dominican or someone who was a professed nominalist – like Walcote, for example.

Читать дальше