Abigny was sitting near the hearth with his boots off and his toes extended towards the flames, while Philippa perched next to him, attempting to sew in the unsteady light. The garment was long and white, and Bartholomew saw it was a shroud for her husband to wear on his final journey. She was dressed completely in black, following the current fashion for widows who could afford it. Edith was at the opposite end of the room, sitting at a table as she wrapped small pieces of dried fruit in envelopes of marchpane. Michael went to sit next to her, and it was not long before a fat, white hand was inching surreptitiously towards the sweetmeats.

‘Those are for the apprentices,’ came an admonishing voice from the shadows near the door. Michael almost leapt out of his skin, having forgotten that Cynric had been charged to stay with Edith while Stanmore was out.

‘God’s blood, Cynric!’ muttered the monk, holding a hand to his chest to show he had been given a serious fright. ‘Have a care whom you startle, man!’ He helped himself to a handful of the treats, indicating that he needed them to help him recover from the shock.

‘Did you bring that potion for my feet?’ asked Abigny eagerly of Bartholomew. ‘I long to be relieved of this constant pain. I know you dislike calculating horoscopes, Matt, but I am your friend and my need is very great, so I am sure you will not refuse me. Do you know enough about me already to determine the course of treatment, or are there questions you need answered?’

‘The latter,’ said Michael, not very subtly. ‘He needs to know whether you have spent much time walking in the snow of late.’

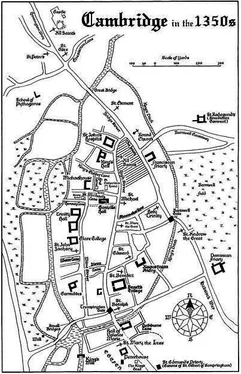

‘Of course I have,’ said Abigny, surprised by the question. ‘First there was the journey to Cambridge, and then there have been old friends to see and arrangements to make.’

‘Arrangements?’ asked Michael innocently.

‘Now that Walter is dead I may lose my post,’ replied Abigny, apparently unconcerned by Michael’s brazen curiosity. ‘So, I went to see a Fellow at King’s Hall, who has agreed to provide testimony that I am an honest and responsible citizen. And I have been obliged to visit coffin-makers and embalmers.’ He regarded Bartholomew with innocent blue eyes. ‘Are these the kind of things you need to know for my stars, Matt?’

His answers came a little too easily, and Bartholomew could not help but conclude he had been thinking about what to say. Abigny continued to talk, regaling them with dull and unimportant details of a meeting he had had with the Warden of King’s Hall, and giving details of various important dates in his life, which Michael pretended to write down so the horoscope could be constructed later.

Meanwhile, Bartholomew inspected Abigny’s feet, wincing when he saw the huge chilblains that plagued the man’s toes and heels. He was not surprised Abigny limped, and set about making a poultice of borage and hops to ease the swelling. He also prescribed a soothing comfrey water that would reduce Abigny’s melancholic humours and restore the balance between hot and cold, and recommended that his friend should avoid foods known to slow the blood. Philippa offered to purchase her brother warmer hose to prevent his feet from becoming chilled in the first place.

She rose from her seat when Bartholomew had finished examining Abigny, and asked to be excused. She was pale, and there were dark smudges under her eyes – as expected in a woman who had recently lost her husband. Before she left, she fixed Bartholomew with a worried frown.

‘You will not disregard my request, will you, Matthew? Walter is dead, and nothing can bring him back. He was not popular and did not always treat people with kindness or fairness. If you ask questions about him you will certainly learn that, even here in Cambridge where he was not well known. But I do not want you to encourage people to speak badly of him. I want him to rest in peace. It is no more than any man deserves.’

‘Men deserve to have their deaths investigated if there are inconsistencies and questions arising,’ said Michael gently. ‘Walter will not lie easy in his grave if these remain unanswered.’

‘There are no questions,’ said Philippa stubbornly, her eyes filling with tears. ‘He drowned. You saw that yourselves.’

‘He died from the cold,’ corrected Bartholomew. ‘The water in his lungs did not–’

Philippa turned angrily on him, and the tears spilled down her cheeks. ‘It does not matter! He died, and whether it was from the cold or by water is irrelevant. This is exactly what I am trying to avoid – pointless speculation that will do nothing but disturb his soul.’

‘If there are questions, then they originated with you,’ Michael pointed out, unmoved by her distress. ‘You were the one who insisted that Walter would not have gone skating.’

She stared at him, tears dripping unheeded. ‘I was distressed and shocked, and I said things I did not mean. Walter was not a man for undignified pursuits, like skating. But then he was not a man who undertook pilgrimages, either – yet that is why we are here. Perhaps the religious nature of his journey made him behave differently, but it does not matter because we will never know what happened. All I can do is console myself that he died in a state of grace, because he was travelling to Walsingham, and pray that God will forgive him for the incident regarding Fiscurtune.’

‘The “incident” would not have led him to take his own life, would it?’ asked Michael, beginning a new line of enquiry. Philippa was right, in that pilgrimages sometimes had odd effects on people and it was not unknown for folk to become so overwhelmed by remorse for what they had done that they killed themselves.

Philippa shook her head. ‘Walter was not a suicide, Brother. The Church condemns suicides, and Walter would not have wanted to be buried in unhallowed ground.’

Bartholomew did not point out that securing a suitable burial place was usually the last thing on a suicide’s mind, but agreed that Turke had not seemed the kind of man to take his own life. He watched her leave the solar, then turned to stare at the flames in the hearth, while Abigny hobbled after her in his bare feet. Was she hiding information about her husband’s death, either something about the way he had died or some aspect of his affairs that led him to his grim demise in the Mill Pool? Was Stanmore right: that Philippa or Abigny – or both – had decided to kill Turke while he was away from his home and his friends? Had Turke been skating, or did someone just want everyone to believe he had?

He reached for his cloak, nodding to Michael that they should leave. Answers would not come from Philippa or her brother, since neither was willing to talk. He and the monk needed to look elsewhere.

That night was bitterly cold, with a frigid wind whistling in from the north that drove hard, grainy flakes of snow before it. The blankets on Bartholomew’s bed were woefully inadequate, and he spent the first half of the evening shivering, curled into a tight ball in an attempt to minimise the amount of heat that was being leached from his body by the icy chill of the room. In the end, genuinely fearing that if he slept in his chamber he might never wake, he grabbed his cloak and ran quickly through the raging blizzard to the main building in the hope that there might be some sparks among the ashes of the fire that he could coax into life.

A number of students were in the hall, wrapped in blankets, cloaks and even rugs as they vied with each other to be nearest the hearth. The door to the conclave was closed and Bartholomew hesitated before opening it, suspecting that Deynman and his cronies would be within, plotting his next move as Lord of Misrule. But an ear pressed against the wood told him no one was talking, so he opened it and entered, tripping over the loose floorboard as he went.

Читать дальше