‘Not exactly. I did not know what to think. She came with her husband, who was undertaking a pilgrimage.’

‘But he is now dead and she is a widow,’ said Matilde. ‘That means that she is free to pursue any potential partner she pleases. Perhaps she will pursue you.’

‘She has grown too large to pursue anyone, I would imagine,’ said Michael, blithely ignoring the fact that he cut no mean figure himself. ‘Still, I suppose she may hanker for the handsome physician who captured her heart when she was in the flower of her youth.’

‘Her husband was very wealthy,’ said Matilde, addressing Bartholomew. ‘So, your Philippa is probably anticipating a rosy future for herself.’

‘She is not “my” Philippa,’ said Bartholomew, a little nettled. ‘And I am sure Turke’s sons will inherit most of his wealth, if not all of it. Indeed, she may be even poorer than me.’

‘We shall see,’ said Matilde, retrieving the basket from him when they reached St Michael’s Lane. Without a backward glance, she walked away, heading for the sorry hovels that lined the river bank. Bartholomew gazed after her, resentful of her insinuations, while Michael chuckled softly.

‘She is jealous, Matt. That is a good sign. Now you have two women who would like you to be their husband – a fat, greedy widow or a retired courtesan. It is quite a choice!’

‘There is Giles Abigny,’ said Bartholomew, recognising the short, neat figure hurrying through the Trumpington Gate before a heavy dray cart pulled by four large horses blocked it. Abigny wore his travelling cloak and his brown hat with the drab plume. Michael headed towards him, the rotten fish still clamped under his arm, and Bartholomew began to wonder whether they might be destined to spend the whole day in company with the thing.

‘Nasty weather,’ said Abigny amiably, rubbing his gloved hands together in an effort to warm them. ‘I do not recall another winter like it. Did you know that the London road is now totally blocked? And the Ely causeway has been impassable since before Christmas, or Philippa and I would have left by now. We are marooned, unless we want to go to Huntingdon.’ He shuddered fastidiously.

‘Where have you been?’ asked Michael, glancing through the gate at the snow that was piled high on each side of the road to Trumpington. ‘It is no day for a stroll, and you are limping.’

Abigny grimaced, and raised one foot to show where the leather on his boot had been slit. ‘Chilblains. You have no idea how painful they can be. I always thought they were an old man’s complaint, so what does that tell you about me, Matt?’

‘That you should wear thicker hose and larger shoes,’ said Bartholomew. ‘And that you should wash your feet each night to ensure the wounds do not fester. Do you want a potion to ease the discomfort?’

Abigny shot him a surprised smile. ‘My old room-mate is a physician, and yet I did not think to ask him for a remedy! I would be eternally grateful if you could provide me with anything that would make walking less of an ordeal. When can I have it?’

‘I will bring it this afternoon.’

‘If walking is so painful, then why are you out?’ asked Michael nosily.

‘I had business to attend,’ said Abigny. He gave the monk a faint smile. ‘You do not want the details. Suffice to say that arranging the transport of a fishmonger’s body to a distant burial site is not an easy matter. There are many factors that need to be taken into account.’

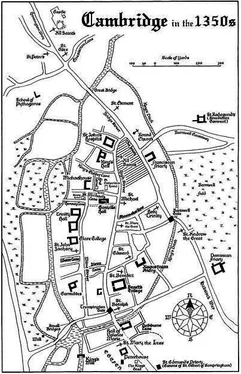

‘Out there?’ asked Michael, indicating the Trumpington Road, where there stood two Colleges, the King’s Head, a church, two chapels, the Gilbertine Friary, a windmill and a smattering of houses, but nothing that would help solve the problems associated with taking a corpse to London.

‘Out there,’ agreed Abigny with an enigmatic smile. ‘But it is too chilly to talk here and my feet pain me. I am sure you two have much to occupy your time, so I shall be on my way. Do not forget that potion, Matt. If you deliver it today, I shall leave you my worldly goods when I die.’

‘Your fiancée might have something to say about that,’ said Bartholomew. He watched Abigny hobble away, then turned to Michael. ‘What did you make of that?’

They started walking again, but had the misfortune to meet a cart coming the other way, spraying up dirty snow with its great wooden wheels as it went. Bartholomew ducked behind a stack of barrels, but Michael did not, and swore furiously at the grinning carter while he brushed the filth from his cloak.

‘What do you mean?’ demanded the monk testily, looking in both directions for more carts before making his way to the tavern. ‘Make of what?’

‘Make of the fact that Giles is in pain, yet is willing to walk outside the town. You know as well as I do that no embalmers or coffin-makers live out here. So, what was he doing?’

‘He has behaved oddly ever since he arrived,’ said Michael. ‘Like Philippa’s, his reaction to Turke’s death is curious. I told you yesterday there was something unsavoury about the whole incident, and Giles’s secretive manner has done nothing to make me think any differently.’

‘Turke’s death and the fact that Philippa did not mention she had hired the Chepe Waits in London,’ added Bartholomew. ‘Frith and Makejoy told me about that, and so did Quenhyth.’

Michael shrugged. ‘I do not think the Waits are important – not like her strange reaction to her husband’s death. Perhaps she had simply forgotten about the jugglers. Even you must see that a band of travelling entertainers is not something that is likely to occupy the mind of a woman with a household to run for very long.’

‘I disagree. Entertainers are hired for important occasions – events that stick in people’s memories. And the Waits are memorable, because their act is so poor.’

‘Perhaps there were more talented members in the troupe at that time,’ suggested Michael. ‘Or they wore different costumes.’

‘Not according to Quenhyth. He recalls them just as they are – the same people and the same clothes.’

‘So, what are you saying? That Philippa has a sinister motive for not telling you she hired a troupe of vagrants? Perhaps she wants to woo you – as Matilde believes – and thinks admitting to an association with the Chepe Waits will put you off. Or perhaps she guessed – correctly, I imagine – that you would not be interested in the details of her household affairs. Talking about how to hire vagrants is not recommended as a topic to impress potential suitors with.’

‘I am not a potential suitor,’ objected Bartholomew. ‘And even if she regards me as fair game now – which I am sure she does not, given that she decided against me when I was younger, fitter and less grey – she certainly did not do so while her husband ate his dinner next to her.’

Michael raised his eyebrows, his expression mischievous. ‘She may have realised Turke ranked a poor second to your charms, and so decided to move him into the next world.’

Bartholomew sighed impatiently. ‘Do not be flippant, Brother! I am uneasy about this link between her and the Waits. There is also the fact that her dead manservant – Gosslinge – was in the King’s Head with Frith. I am sure it is significant.’

‘Do not forget we have been told that Harysone was in the King’s Head with the Waits, too,’ said Michael. ‘So, what shall we do? Shall we arrest Philippa and take her to my prison, where I can question her about the men she hired last summer? Or shall I arrest the Waits, and demand to know why Philippa denied knowing them?’

Bartholomew gave him a rueful smile. ‘You are right, there is nothing to be gained from these speculations. Philippa will be gone as soon as the snow clears, and I will probably never see her again.’

Читать дальше