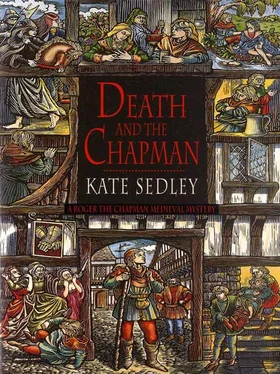

Kate Sedley - Death and the Chapman

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Kate Sedley - Death and the Chapman» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Death and the Chapman

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Death and the Chapman: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Death and the Chapman»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Death and the Chapman — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Death and the Chapman», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

He grunted. ‘You may have to sleep in the kitchen if we’ve managed to rent out your room.’ He obviously deplored Thomas’s open-handedness.

‘Of course!‘ I smiled disarmingly. ‘Master Prynne has already made that plain.’

Then, whistling, I turned and walked out into the street.

At the top of the lane I paused, staring into the courtyard of the Crossed Hands inn. I wondered if I could chance my luck and get inside, without encountering Martin Trollope. But just at that moment he appeared on the balcony, shouting down to one of the ostlers who was leading a horse out of the stables. I badly wanted to speak to Matilda Ford again, but decided that the time was not propitious.

I had decided over breakfast, that this morning I would sell my wares in the Farringdon Ward, going from house to house, knocking on doors. That way, I hoped to locate the Alderman’s brother, John Weaver, and learn anything he could tell me. Consequently, I made my way along Cheapside and out through the New Gate to the noisy, stinking cattlemarket of Smithfield, where, on great occasions, tournaments and jousting were held. Beyond, lay St Bartholomew’s Priory, famous for its annual fair, the numerous Inns of Chancery and the long string of shops and houses strung out along the River Fleet.

It was more than half way through the morning before, quite by chance, I knocked on John Weaver’s door. As I put the question I had posed at every house so far — ‘Can you tell me where John Weaver of Bristol lives? — ’ the sallowfaced girl who had appeared in the doorway asked pertly: ‘And why would that be any concern of yours?’

‘I have a message,’ I answered, ‘from his brother, the Alderman.’ And when she still hesitated, I added: ‘Of Broad Street, in Bristol.’

‘Wait here,’ she snapped. ‘I’ll fetch Dame Alice.’ Dame Alice was a stout, pleasant-faced woman, who wheezed distressingly whenever she was flustered, as she appeared to be now. Her faded blue eyes were wide with suspicion, wisps of hair escaping from beneath her white linen cap.

‘Are you the chapman?‘ she asked unnecessarily, eyeing my pack. ‘My daughter-in-law says you have a message for my husband.’

‘Is he at home?’ I inquired politely.

She shook her head. ‘He’s over at Portsoken with George and Edmund.’ These, presumably, were the two sons whom Alison had mentioned. ‘The weavers need constant supervision, you know. You can’t just leave them to their own devices. A lazy, idling, good-for-nothing set of people.’ She spoke without rancour, simply endorsing her menfolk’s opinions, as was seemly in a woman. ‘He won’t be home until just before curfew, but you can go over there and find him, if you like.’

I had no desire to leave the lucrative market of Farringdon Without before I had knocked on as many doors as possible. Already, my pack was greatly depleted: I should need another visit to Galley Wharf tomorrow morning.

‘Perhaps I could leave the message with you?‘ I hazarded. ‘It’s to do with your nephew’s disappearance.’

‘Clement? Oh dear, oh dear! That poor boy! Maybe… Maybe you’d better come in.’

She led me through to the garden at the back of the house, which ran down to the river. The rain had cleared by now, giving way to hazy sunshine and a sky which stretched milk-white above the tree-tops, threaded with faint ribbons of gold. Mistress Weaver and her daughter- in-law, whom she addressed as Bridget, had been picking herbs from the little herb-garden in the shade of one wall. Cumin, fennel and others were heaped in a shallow basket, ready to be dried and stored for the winter. Mistress Weaver folded her hands together nervously over her apron.

‘What… what did my brother-in-law have to say about poor Clement?’

I told her as quickly as I could about my meeting with Marjorie Dyer and my talk with the Alderman, leaving out my subsequent adventures. When I had finished, it was Bridget Weaver who spoke first. Her manner had lost its initial hostility.

‘Poor Uncle Alfred,’ she said quietly. ‘He can’t accept what’s happened. But there’s nothing more we can tell you than you seem to know already. Alison, her maid and the four men — our two, Rob Short and Ned Stoner — arrived here late in the afternoon, not long before curfew. But as soon as Ned had seen Alison safely inside the house, he rode back again to the Baptist’s Head. He was only just in time as it was, before the gates were closed for the night. It wasn’t until next morning that we knew Clement was missing.’

Her mother-in-law nodded. ‘My husband and sons set out for the city immediately and spent the next few days searching every place they could think of where Clement might have gone of his own free will. Not that they, or any of us, had much hope of finding him. We sent one of our men post-haste to Bristol and the Alderman was here within a week, but by then, we knew the worst.’ Mistress Weaver sighed. ‘I realize that it’s difficult for Alfred to accept the truth, particularly without a body to convince him. But, believe me, he’s wasting your time, as well as raising his own hopes falsely. My husband and sons would tell you exactly the same if they were here.’

It was the same story as I had heard before, with always the same conclusion. There was no doubt in anyone’s mind that Clement Weaver had been murdered by footpads. In any mind but mine, that is. I still felt there was a mystery to be unravelled. But there seemed nothing more to be gleaned from either Mistress Weaver or her daughter-in- law, so I said I must be on my way.

‘You must have some refreshment before you go,’ the older woman insisted, and led the way to the kitchen. ‘Bridget, my dear, fetch the chapman some ale.’

But when it came, it was sallop, a ‘poor man’s ale’, made from wild arum. Bridget Weaver was not such a fool as to waste the real thing on a pedlar. The two women drank an infusion of calamint, which my mother had been fond of, swearing by it as a cure for coughs and the ague. They did not offer me a seat, and I stood towering above them, as they sat at the kitchen table. Neither of them offered to buy anything from me.

I was still drinking my sallop when a swarthy, thickset young man entered the kitchen. He bore more than a passing resemblance to Alderman Weaver, so I had no difficulty in placing him as one of the nephews. And as he stooped and gave Bridget a smacking kiss, I guessed him to be her husband. My presence, of course, entailed further explanations, which to my relief were given by Dame Alice. I felt that if I had had to repeat my story again, I should have gone mad.

When she had finished, the young man, whose name I had learned was George, grunted and pulled down the corners of his mouth.

‘Uncle Alfred’s a fool,’ he said, not mincing matters. ‘Clement’s dead. If he wasn’t, we should have heard by now.’ He turned to his mother. ‘Father and Edmund sent me to tell you that they won’t be home for their dinner. There’s trouble among the weavers over at Portsoken. They want more money. They say the cost of bread is rising. They’re talking of sending a deputation to the King, to remind him that he promised to control the price of food this coming winter.’

I remembered what the Canon of Bridlington had written in the previous century: it had been a favourite quotation of our Novice Master at Glastonbury. ‘Any attempt to control prices is contrary to reason. Fecundity and dearth are in the power of God alone, so it follows that the fruitfulness of the soil, and not the ordinances of men, will determine the cost of our goods’ I had always felt that this was a little unfair, making God responsible for our problems.

Bridget said: ‘They’re always making trouble. They want a good whipping. Is there any news from the city?’ George shrugged his big shoulders. ‘Only the same gossip that’s been rife for the past few weeks. The Duke of Gloucester wants to marry Anne Neville and the Duke of Clarence says he shan’t. And the King tries to keep the peace between them.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Death and the Chapman»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Death and the Chapman» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Death and the Chapman» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.