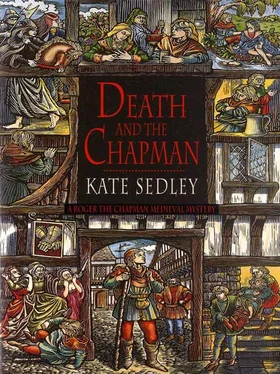

Kate Sedley - Death and the Chapman

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Kate Sedley - Death and the Chapman» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Death and the Chapman

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Death and the Chapman: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Death and the Chapman»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Death and the Chapman — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Death and the Chapman», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Kate Sedley

Death and the Chapman

Part One: May 1471, Bristol

Chapter 1

In this year of our Lord 1522 I am an old man. I’ve lived through the reigns of five kings; six, if you count young Edward. By my reckoning, I’m three score years and ten, the age, so the Bible tells us, which is man’s allotted span on earth, and when my time comes, I shan’t be sorry to go. Things aren’t what they were, as I keep telling my children and grandchildren. And, come to think of it, as my mother told me.

‘Things aren’t what they were when I was a girl,’ she’d say, sweeping hard with her broom and sending the dust and bits of dead rushes flying out of doors, for all the world as though she were trying to sweep modern manners and modern thinking out with them.

I remember that little house in Wells as plainly as ‘though I’d been living there yesterday. My father, on the other hand, is a shadowy figure. Not surprising, really, because he died when I was barely four. He was a stone carver by trade, and very highly thought of, according to my mother. And it’s true that when he died, following a fall from some scaffolding while working on the ceiling of the Cathedral nave, the Bishop — I forget his name, but he was the one before Robert Stillington — paid my mother a small pension out of his own pocket. I think, really, that’s what started all her ideas, wanting me to have an education, to be able to read and write. Which is why she entered me as a novice with the Benedictines at Glastonbury.

Poor woman, she could never see that I wasn’t cut out for the monastic life. I liked the outdoors. I liked being my own master. And I’d absolutely no ear for music. My tuneless’ chanting at the daily offices would drive my fellow novices mad and was only one of the many reasons why they were glad to see the back of me. My good health, which I’ve kept all my life until recently, was another. The other monks and novices were constantly in and out of the Infirmary, especially in winter, but I don’t recall ever having visited it once in all the time that I was at Glastonbury. And I’ve always had excellent teeth, never suffering much from toothache and its attendant ailments. One or two have gone now, of course, and a couple of others give me trouble when the wind’s in the east, but what can you expect, at seventy?

But the real reason I left the Abbey and took to the road, after the death of my mother, was more fundamental than being resented by my fellow inmates. It was between me and God; and the Abbot, who was a wise and tolerant man, understood that. It’s not that I doubt the existence of some other world, some hereafter. It’s simply that I can never be quite certain that Christianity holds all the answers. Often walking through the oak and beechwoods, particularly at dusk, I’ve experienced something of the power which the ancient tree gods exercised over the minds of our Saxon ancestors. Those gnarled, arthritic branches, reaching towards me through the gloom, bring to life some race-memory. More often than I care to admit, I’ve glanced fearfully over my shoulder, expecting, against all reason and faith to see the figure of Robin Goodfellow or Hodekin or the terrible Green Man. Mind you, this is a heresy I’ve kept to myself. I’m not such a fool as to say it out loud. And especially not now, when Pope Leo has just given King Henry the Eighth the title of Fidei Defensor for his written answer to the German monk, Martin Luther. And I’m only committing pen to paper, because I feel I haven’t all that much time left to me. Why do I feel like that? Nothing specific. Nothing I can put my finger on. Just a general feeling of malaise, a reluctance to get up in the mornings, a shortness of temper with my daughter, my sons and their children. I’m tired of modern, forward-thrusting youth with their modern, forward-thrusting ways, and their unshakable conviction that Henry Tudor and his son, our present King, rescued this country from the grip of a monster. It’s my privilege to have met our late King Richard, even to have been of some use to him, God bless him!

But, nowadays, that’s another heresy, and probably worse than the first one. The Richard people talk about now is a hunchbacked monstrosity, steeped in blood and evil. But that isn’t the man that I remember, though I’ve no intention of writing a political tract: just a record of my early life, which in many respects was a strange one.

When my mother died, before I’d taken my final vows, and I felt free to flout her wishes and leave the Abbey, I decided to become a chapman. An unlikely decision, you might think, for a lad who could read and write, hawking silks and laces and suchlike around the countryside. But after those years of being cooped up, hemmed in by rules and regulations, I needed the freedom. I needed to be my own master. I wanted to see different parts of this land of ours, which I knew only very slightly by reputation. Above all, I wanted to see London.

I find that strange now, back here in the heart of Somerset, looking out over the shadowed valleys and thickly-wooded hills, the scent of the warm-smelling earth strong in my nostrils. But in those days, London was my goal, the place where I was to make my fortune. I never did, of course. I wasn’t cut out to be another John Pulteney or Richard Whittington. But if I didn’t make much money, I did find that I had a talent in another direction. I found that I was good at solving puzzles, unravelling mysteries that baffled other people. And really, that’s what these memoirs of mine are all about, in the hope that one day, when I’m dead, my children will be interested enough to read them.

It all began with the case of the disappearance of Clement Weaver, a young man I’d neither seen nor heard of that May morning in the year of Our Lord 1471. I hadn’t long been on the road in those days. My mother had died the previous Christmas, and her thrift had meant that she was able to leave me a small — a very small — sum of money. With it, I had bought my first stock from an old pedlar who was giving up the road to spend his dying years as a pensioner of the monks at Glastonbury, although I was unable to purchase his donkey. But I was young and strong, big and tall for my age, with broad shoulders, and quite capable of carrying my pack on my back. So I set off, full of confidence, walking up from Wells towards Bristol, stopping to sell my wares in the villages through which I passed. I spent May Day at Whitchurch, helping the villagers to bring in the may and then going to church to celebrate the feast of St Philip and St James; for me, a satisfying blend of the ancient tree-worship of our Saxon forebears and the demands of Holy Church which rule all our lives. I approached the walls of Bristol on May 2nd.

I could tell that something untoward was happening while I was still several hundred yards from the Redcliffe Gate. There was an unusual amount of activity, with armed men coming and going, and a crescendo of noise which permeated the town walls like water seeping through a dam. Near the church of St Mary, tents and all the debris of men who had spent a couple of nights in the open, indicated a military camp which was now being struck, the men scurrying about like ants, suggesting that they were in a hurry to be gone. Sudden orders to move on? I wondered. There was more than a hint of panic in the air.

As I neared the gatehouse, the town hermit, ragged, filthy and stinking to high heaven, scuttled out of his hovel to survey me, begging bowl hopefully extended. One glance, however, at my youth, my patched and mended clothes, caused his weatherbeaten face to crumple with disappointment. He muttered something into his matted beard and disappeared again, quickly. Bristol was — still is — a very rich city, second in importance only to London, and he had no time to waste on the obviously poor and needy.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Death and the Chapman»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Death and the Chapman» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Death and the Chapman» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.