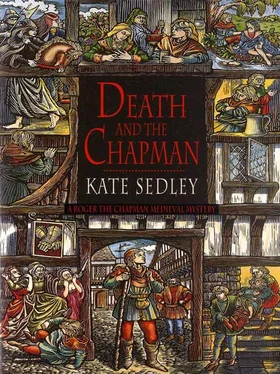

Kate Sedley - Death and the Chapman

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Kate Sedley - Death and the Chapman» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Death and the Chapman

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Death and the Chapman: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Death and the Chapman»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Death and the Chapman — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Death and the Chapman», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I grinned. ‘So I have often been told, Father, but somehow or other, there are always too many questions to which I can find no satisfactory answers.’

A silence succeeded my words while the priest marshalled his forces to deal with this Doubting Thomas. And in the quiet, I caught snatches of a conversation in progress behind me between two women, who, I had decided in my own mind, were mother and daughter. They looked sufficiently like one another to give credence to this theory.

‘… Lady Anne Neville,’ the younger woman was saying, and immediately the name attracted my attention. Once more, I was back in Bristol, watching that unhappy child ride along Corn Street. ‘It’s common gossip that the Duke of Clarence doesn’t want his brother to marry her because it will mean the division of the late Earl’s estates. As husband to the elder daughter, he hopes to get them all. Or as many of them as he legally can.’

‘A downright wicked shame,’ her mother answered warmly. ‘It wasn’t my lord of Gloucester who deserted King Edward in his hour of need.’

‘Oh, the King intends Duke Richard to have Lady Anne, you may be sure of that. But amicably, if possible, with my lord of Clarence’s and Duchess Isabel’s full consent.’

The girl spoke with that assurance I have frequently noticed among the very poor when talking of royal affairs.

And indeed, more often than not, time and events prove them correct. I have pondered the reason for this, and have come to the conclusion that it is because their own existences are so uninteresting and drab that they live vicariously through others more glamorous than themselves. They look and watch and listen, hoarding scraps of information as some of their fellows hoard money, assessing, interpreting and making valid judgements.

‘It would be a good match,’ the older woman agreed, ‘and please the people. Please themselves as well, no doubt, for they’ve been friends since childhood, and that’s a fact. Brought up together in the North, and always intended for one another by her father…’

I could overhear no more. The priest was speaking again, invoking the teachings of St Augustine in his argument and desperately trying to convince me that obedience was all. I answered randomly, letting him think that he had won our battle of words, too excited now to think of anything but that I was at last within a mile or so of London, that city whose streets were reputedly paved with gold, and which had seen the making and the breaking of so many better men than I. According to my informants who had been there, it was so much bigger, dirtier, noisier, wickeder, more beautiful, more exciting, more interesting than anywhere else in England — some people said than anywhere else in Europe — that my heart was beating almost suffocatingly in anticipation. And towards evening, with the sky trailing great ragged banners of blood-red, amethyst and flame, when the distant trees netted the final rays of the sun and seemed to catch fire from within, I saw London for the very first time, lying like a smudged thumb- mark on the horizon. Somewhere inside those walls lay the answer to the riddle of Clement Weaver’s and Sir Richard Mallory’s disappearance. Whether or not it would ever be solved was now up to me.

Part Three: October 1471, London

Chapter 9

Old age is not simply a matter of rheumatic joints, defective eyesight and impaired hearing; it’s waking up one morning and realizing that there is no longer any future. That is a lesson I have learned these past few years, and something which young people find very hard to grasp. They have life, love and adventure spread before them, without any hint of their own mortality.

I was exactly the same myself, on that early October day in the year of Our Lord 1471 when I crossed London Bridge and entered the city proper for the very first time. It was, as I recall, a morning of frost and needle-sharp sunlight, all white and gold. Everywhere there was brilliance and light, from the sparkle of rimed branches and rooftops to the glitter of the rutted road and the sun-spangled glint of horses’ harness. I was young, strong and ready to take on the world. The thought of any personal danger in the quest which lay in front of me never so much as entered my mind.

I had spent the night in Southwark, at the home of one of my new acquaintances. And it was thanks to him that I had acquired my first knowledge of the capital. Stretched beside him on the floor of his master’s bakery, saved from the cold of the night by the warmth of the ovens, I had nevertheless found it difficult to sleep on account of the noise from the house next door. In the chill of the small hours, when my friend rose to rekindle the fires for the early baking, he discovered me wakeful. When I explained my problem, he laughed.

‘I should have warned you,‘ he said, ‘ that the house next to this is a brothel. There are dozens of them in Southwark, all belonging to the Bishop of Winchester, so the local whores are known as Winchester geese.’ He also told me that I could recognize a prostitute by the striped hood she wore.

I was naive enough in those days to be shocked by this information. Innocent that I was, I had believed until then that all churchmen, fallible human beings though they were, at least abided by the rule of chastity and assisted laymen to do the same, even if they were often unsuccessful. To find out that the See of Winchester actually owned houses of ill repute gave me a jolt from which I did not soon recover.

But now, as I approached the already lowered drawbridge, my stomach full of a shared breakfast of porridge and small beer, my pack comfortably settled on my back, my cudgel swinging in my hand, I had no thoughts for anything but my first real sight of London. At the southern end of the bridge were three stone towers with portcullises, the outer two topped by a row of traitors’ heads on spikes, each sightless, grinning mask in a different stage of decomposition.

I had no difficulty passing through the gate, but the Warden had little time to answer my request for directions. ‘Cross the bridge and ask again,’ he grunted, and indeed I could see that he was busy. I had never encountered such traffic as there is in London, nor so many people. I had been told by one of the pilgrims that it was home to some forty or fifty thousand inhabitants, but my mind refused to encompass so vast a number. Now, jostled on every side by carts and waggons and foot travellers like myself, I was overwhelmed by the noise and general air of confusion. The surface of the bridge, between the two rows of overhanging shops and houses, was badly pitted, and on at least three occasions I stumbled, twisting an ankle. But each time a neighbourly hand caught my elbow and prevented me from falling. I decided that London might be overcrowded and rowdy, but the people were friendly. Long before I had reached the end of the nineteen-arch span, I was feeling more cheerful and less intimidated.

I had been advised by my host of the night to make for one of the quays east of London Bridge, where ships coming up river from the mouth of the Thames docked at the wharfside and sold goods direct to customers on shore. And after my success in Canterbury my pack was in need of replenishing. Once clear of the bridge itself, I had a better view of the river, already bustling, even at that early hour of the morning, with boats and barges of all shapes and sizes. There were swans, too, gliding gracefully through the waterborne traffic, apparently unperturbed by the movement. I could see groups of men around the piers of the bridge, fishing for the smelts and salmon, pike and tench and barbel, with which the river abounded. (I learned later that they were known as Petermen, because they used nets, like St Peter.)

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Death and the Chapman»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Death and the Chapman» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Death and the Chapman» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.