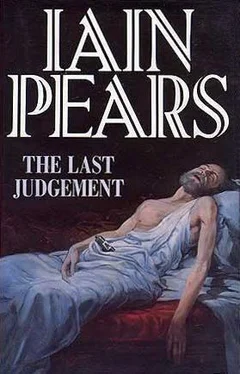

Iain Pears - The Last Judgement

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Iain Pears - The Last Judgement» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 1993, ISBN: 1993, Издательство: Victor Gollancz, Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Last Judgement

- Автор:

- Издательство:Victor Gollancz

- Жанр:

- Год:1993

- Город:London

- ISBN:978-0575055841

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Last Judgement: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Last Judgement»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Last Judgement — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Last Judgement», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

By the time Argyll got back from his errand, Flavia was making up for lost time. She’d bathed, collapsed on the bed, and was so profoundly unconscious she could well have been in advanced rigor mortis. Argyll found her, breathing softly, her mouth open, her head resting on her arm, curled up like a hamster in full hibernation and, much as he wanted to prod her and tell her his little stories, he let her be. Instead, he watched her awhile. Watching her snooze was a favourite occupation of his. How you sleep is a good indication of what you are like: some people thrash around and mutter to themselves, constantly in turmoil; or regress to childhood and stick their thumbs in their mouths; some, like Flavia, manifest a deep-seated tranquillity that is often disguised when they are awake. For Argyll, watching Flavia sleep was almost as restful as sleeping himself.

As spectator sports go, however, it could command the attention for only a short time, and after a while he left to go for a walk. He was feeling quite pleased with himself. See if you can talk to Rouxel, Flavia had instructed and, obedient as he was, that was exactly what he’d done. When he’d left Jeanne Armand, he’d promised to bring the picture round the next day; the implication was that he would take it round to her apartment. But there was no reason why he shouldn’t indulge himself in a little misunderstanding so, taking the picture, a taxi and what money he had, he’d gone out to Neuilly-sur-Seine.

A suburb just outside Paris proper, Neuilly is very much a place for the rich middle classes who have the funds to indulge their tastes. Apartment blocks began to spring up in the 1960s, but many of the villas built there still survive, small monuments to France’s first flirtation with the Anglo-Saxon ideal of gardens and privacy and peace and quiet.

Jean Rouxel lived in one such villa, an 1890s’ rusticated art nouveau affair, surrounded by high walls and iron gates. When he arrived, Argyll rang the bell, waited for the little buzzer indicating that the gate had been unlocked, then marched up the garden path.

Rouxel had taken the possession of a garden seriously. Although the English eye could fault the excessive use of gravel and look a little scornfully at the state of the lawn, at least there was a lawn to look scornfully at. The plants were laid out with care as well, with a distinct attempt at the cottage-garden look of domesticated wildness. Certainly there was none of the Cartesian regimentalism with which the French so frequently like to coerce nature. Just as well; however geometrically satisfying, there is always something painful to the English eye about French gardens, creating a tendency to purse the lips and feel sorry for the plants. Rouxel was different; you could tell at a glance that the owner was inclined to let nature take its course. It was a liberal garden, if you can attribute political qualities to horticulture. Owned by someone who was comfortable with the way things were, and didn’t want to tell them how they should be. Good man, thought Argyll as he crunched up the path. It is dangerous to form an opinion about someone merely on his choice of wisteria, but Argyll was half inclined to like Rouxel even before they’d met.

He was even more so inclined when he did. He found Rouxel outside, around the side of the house, looking pensively at a small flower-bed. He was dressed as people should be on a Sunday morning. As with gardens themselves, there are two schools of thought on this: the Anglo-Saxon, which prefers to slope around looking like a vagabond, in old trousers, crumpled shirt and sweater with holes symmetrically located at both elbows. Then there is the Continental school which dons its best and presents itself to the outside world in a haze of eau-de-Cologne after hours of preparation.

However much he was the epitome of French values, Rouxel belonged, sartorially, on English territory. Or at least on an off-shore island: the jacket was a bit too high-quality, the trousers still had a crease in them and the sweater only had one, very small, hole in it. But he was trying, no doubt about it.

As Argyll approached with an amiable smile on his face and Socrates under his arm, Rouxel grunted, bent over — stiffly, as you’d expect from a man in his seventies, but with signs of suppleness none the less — and pounced on a weed, which he ripped out and eyed with triumph. He then placed it carefully in a small wicker basket hanging on his right arm.

‘They’re a devil, aren’t they?’ said Argyll walking up. ‘Weeds, I mean.’

Rouxel turned round and looked at him puzzled for a moment. Then he noted the package and smiled.

‘You’ll be Monsieur Argyll, I imagine,’ he said.

‘Yes. Do forgive me for disturbing you,’ Argyll said as Rouxel looked placidly at him. ‘I hope your granddaughter told you I would be coming...’

‘Jeanne? She did mention she’d met you. I didn’t realize you’d be coming here, though. No matter, you’re most welcome. Let me just get this little one here...’

And he bent down again and resumed the attack on his incipient bindweed problem. ‘There,’ he said with satisfaction when this too had been consigned to the basket. ‘I do love my garden, but I must confess it is becoming a bit of a burden. A brutal occupation, don’t you think? Constantly killing, and spraying and rooting out.’

He had an impressive voice, mellow and well modulated with an underlying vitality of considerable power. Of course, he had been a lawyer, so it was probably part of the job; but from the voice alone, Argyll could see why a run at politics had been tempting. It was the sort of voice that people trust — as well as being the sort of well-honed instrument that could change in a flash to threat, anger and outrage. Not a de Gaulle voice; not the rolling oratorical style which gains your wholehearted support even if, like Argyll when he first heard one of the General’s speeches, you don’t have a clue what he’s talking about because it’s all in French. But certainly a match for all modern French politicians Argyll had ever heard.

So while they both looked carefully for any more weeds, Argyll apologized once more and explained that he’d wanted to return the picture as soon as possible so he could get back to Rome. As he’d hoped, Rouxel was delighted, considerably surprised, and, as any well-brought-up gentleman should, responded by insisting, absolutely insisting, that dear Mr Argyll should come in and take a cup of coffee and tell him the whole story.

Mission accomplished, Argyll thought as he settled himself down in an extremely comfortable stuffed armchair. Another point in the man’s favour. Of all the houses Argyll had ever been in in France, this was the first one to have even remotely comfortable furniture. Elegance, yes. Style aplenty. Expensive, in many cases. But comfortable? It always seemed designed to do to the human body what French gardeners liked to do to privet hedges, that is, bend and distort them out of all recognition. They just have a different idea of what relaxation is.

And on top of that, Argyll even approved of his pictures. He was in the man’s study, and it was lined with a comfortable jumble of paintings and photographs and bronzes and books. By the large glass doors leading on to the garden was further evidence of Rouxel’s enthusiasm for gardening: an impressive array of healthy, and no doubt well-sprayed, house plants. Faded Persian rugs on the floor, evidence of a large dog from the excessive amounts of moulted hair scattered around. One wall was covered in mementoes of a career in and out of public service. Rouxel and the General. Rouxel and Giscard. Rouxel and Johnson. Rouxel and Churchill even. Pictures of awards, records of honorary degrees, this and that. Argyll found it charming. No false modesty, but no boasting either. Just a quiet pride, hitting exactly the right tone.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Last Judgement»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Last Judgement» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Last Judgement» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.