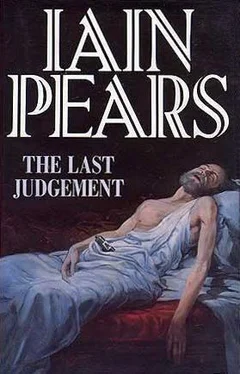

Iain Pears - The Last Judgement

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Iain Pears - The Last Judgement» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 1993, ISBN: 1993, Издательство: Victor Gollancz, Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Last Judgement

- Автор:

- Издательство:Victor Gollancz

- Жанр:

- Год:1993

- Город:London

- ISBN:978-0575055841

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Last Judgement: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Last Judgement»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Last Judgement — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Last Judgement», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘Flavia!’ Argyll said as he appeared, in much the same tone as you’d expect from a stranded mountaineer greeting his favourite St Bernard as it turns up with a keg of brandy.

‘There you are. Where have you been at this ungodly hour?’

‘Me? Oh, nowhere, really. Just to get some cigarettes. That’s all.’

‘Just after eight on a Sunday morning?’

‘Is it? Oh. I couldn’t sleep. I’m so pleased to see you. Here.’

And he wrapped his arms around her and hugged her with a vehemence she had not noticed in him before.

‘You look really beautiful,’ he said, standing back and looking at her admiringly. ‘Quite wonderful.’

‘Is anything the matter?’ she asked.

‘No. Why do you ask? But I had an awful night. Tossing and turning.’

‘Why was that?’

‘Oh, nothing. I was thinking.’

‘About your picture, I suppose?’

‘Eh? No, not about that. I was thinking about life. Us. That sort of thing.’

‘What?’

‘It’s a long story. But I was wondering what it would be like if we split up.’

‘Oh, yes?’ she said, a little perturbed. ‘What makes you think of that?’

‘It would be awful. I couldn’t face it.’

‘Ah. Why is this in your mind at the moment?’

‘No reason,’ he said brightly, thinking about the previous evening and his decision about apartments. She was going to take some persuading. The old charm was going to be needed. Not that he mentioned any of this, with the result that Flavia was forced to conclude that he was going slightly wobbly on her. This sort of gushing he normally kept to himself. He was English, after all.

‘Do you have any money?’ she asked eventually. No point in pursuing this bizarre mood of his, after all. And it was early.

‘Yes. Not much.’

‘Enough to buy me breakfast?’

‘Enough for that, yes.’

‘Good. So take me somewhere. Then you can tell me what you’ve been doing in the few minutes I have before I fall asleep for ever.’

‘That’s not bad at all,’ she said, two coffees and a measly croissant later. A bit patronizing really, but she was too tired for subtlety. ‘If I grasp it right, you think that Muller may have contacted Besson after this exhibition, Besson pinched the thing and delivered it to Delorme. Then Besson gets arrested, Delorme panics and unloads it on to you. The man with the scar talks to Delorme pretending to be a policeman, finds out that you have the thing, and tries to pinch it at the Gare de Lyon. He then trails you to Rome, goes to Muller and wham. Exit Muller.’

‘An exemplary summary,’ Argyll said. ‘You should have been a civil servant.’

‘I, meanwhile, have discovered that Muller had been obsessed by this picture for the past two years, believing it contained something of value. He thought it belonged to his father who hanged himself. The trouble is this Ellman character. Why would he come to Rome as well? The Paris phone call could have come from your man with the scar, but why would both of them turn up in Rome?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘There’s no chance the phone call came from Rouxel?’ she went on.

‘Not according to his granddaughter, no. That is, she’d never heard of Ellman and deals with all Rouxel’s mail and stuff. Besides, she said he’d given up hope of finding the picture. Wasn’t even looking.’

She yawned mightily, then looked at her watch. ‘Oh hell, it’s ten o’clock.’

‘So?’

‘So I hoped to have a bath and a lie-down, but there isn’t time. I have to get to the airport by midday. Ellman’s son is due back. I want to have a little chat with him. Not that I’m looking forward to it.’

‘Oh,’ said Argyll. ‘I was hoping to spend some time with you. You know. Paris. Romance. That sort of thing.’

She looked at him incredulously. His sense of timing was sometimes so bad it defied the imagination.

‘My dear demented art dealer. I have had four hours’ sleep in the past two days or something. I have not had a bath for such a long time I don’t know if I could remember how to run the water. People sitting next to me on the Métro get up and move away. I have no clean clothes, and a lot of work to do. I am not in the mood either for romance or sight-seeing.’

‘Ah,’ he said, continuing the monosyllabic style he had settled on. ‘Shall I come with you to the airport?’

‘No. Why don’t you take that picture back?’

‘I thought you wanted to examine it?’

‘I did. But you tell me there’s nothing to examine...’

‘There isn’t. I’ve been sharing a bed with Socrates for the past day or so. I know it inside and out, up and down. There ain’t nothing there.’

‘I believe you,’ she said. ‘You’re the expert. And I thought, now if you took it back, you might get to talk to Rouxel. See if he knows anything that might be of help. Ask him about Hartung. Ellman. Somebody must connect these two somehow. You know. Probe.’

Then, looking at her watch again and tutting about how late she was, she ran off, leaving Argyll to pay the bill. She came back a few moments later, just for long enough to borrow some money off him.

Getting to Charles de Gaulle is not the sort of thing you do in a taxi if your boyfriend has only grudgingly given you two hundred francs to last the day. Admittedly it was nearly all that he had on him, but not princely. So she took one as far as Châtelet, then wandered around, getting increasingly anxious, in the semi-lit subterranean corridors, wandering where, in this vast underground mausoleum, they actually kept the trains. By the time she’d tracked the right one down, hidden cunningly among the booths and leather-goods stalls, and got on board, she was in no mood to be soothed by the music which wafted across the platform to her ear-drums. She was in a sweat of anxiety which, considering her state, wasn’t a good idea. If she didn’t have a bath soon, she’d have to burn these clothes.

She got to the airport about twenty minutes after Ellman junior’s plane was due to land, and then had to wait for a bus to get to the right terminal. Then she ran all the way up to Arrivals, anxiously scanning the notice-boards. ‘Baggage in hall,’ she was told, damn it. There was not much point in just standing and staring at the tired and weary passengers as they trooped past, so she ran to the enquiries desk and got them to put out a message.

Then she stood around, stifling another fit of yawns, and waited. It wouldn’t be a disaster if she missed him, so she thought. But it would be a great shame, and involve not only her having to go back to Switzerland, but also subjection to Bottando’s ironic looks when he examined her expenses, coupled, no doubt, with muttered comments about attention to detail.

She was still thinking along these lines when she noticed the man on the desk pointing her out to a newly arrived traveller. She had formed a picture of Bruno Ellman from the description given by the housekeeper. Not a flattering one at all, despite her attempts to keep an open mind. A playboy type, was what she’d come up with. Expensive khaki trousers, safari gear, a large Nikon. Sunburnt, extravagant and bit of a parasite.

What she got instead was very different. For a start, he was in his forties, if only his early forties. A bit paunchy, with too much starch in his diet. Rumpled clothes whose condition could not be attributed solely to an overnight flight in an aircraft. Hair thinning on top, with what remained turning a little grey.

Must have made a mistake, she thought, as the man came up and introduced himself and proved her wrong. It was Bruno Ellman.

‘I’m so glad you heard the message,’ she said in French. ‘I was afraid I’d missed you. Is French OK?’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Last Judgement»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Last Judgement» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Last Judgement» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.