Дональд Уэстлейк - Help, I Am Being Held Prisoner

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Дональд Уэстлейк - Help, I Am Being Held Prisoner» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1974, ISBN: 1974, Издательство: M. Evans, Жанр: Иронический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

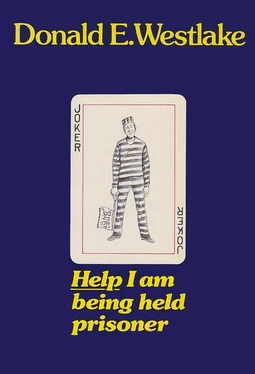

- Название:Help, I Am Being Held Prisoner

- Автор:

- Издательство:M. Evans

- Жанр:

- Год:1974

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-87131-149-8

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Help, I Am Being Held Prisoner: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Help, I Am Being Held Prisoner»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

In the jail he meets seven tough cons with their own private tunnel into the prison town, making them the world’s first prisoner commuters.

Help, I Am Being Held Prisoner — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Help, I Am Being Held Prisoner», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The man with the sideburns was a very calm type. “No, you don’t,” he said, and went out and did exactly what Phil had told him to. He picked up a piece of paper from a desk over there, nodded at the cops, and walked back. “Fine,” Phil said. “Sit down again.”

He gestured with the piece of paper. “I’ll want to put this back again if I may. I don’t want any more disruption of files than absolutely necessary.”

“Sure thing,” Phil said. “Only wait a minute, okay?”

“Of course.”

And by the end of that exchange the cops had left. Seeing a face they knew, in calm circumstances, had convinced them. They went away, the man with the sideburns put the piece of paper back on the desk where it belonged, and we settled down to inactivity and boredom again.

And the beginning of bad news from the vault. A total of ten cartons full of money had been packed from the Fiduciary Federal vault, which was all the cash Jerry and Billy found in there, but progress toward the Western National vault was slower than expected, and very difficult. The removal of the partitions had been a long slow process, requiring frequent intervals of no activity while metal was cooling, and the vault wall when they reached it turned out to be solid concrete, full of metal rods, heavy mesh and cable. Concrete was harder to laser than metal. They couldn’t slice away great pieces of it the way they’d done with the partitions; instead, they had to more or less melt every bit of it, turning it from concrete into lava, boring an ever-widening circle and trying for tiny advantages.

The advantages were few, the disadvantages many. The concrete, in its molten form, ran down over other concrete yet to be melted, where it cooled and hardened again into something glasslike, much tougher than it had been before as concrete. Sometimes this glasslike skin wound up on top of concrete that itself had to be melted, so first the hardened lava had to be re-melted again.

Also, the lava was dangerous to be around; it occasionally splashed, sometimes popped, and constantly ran. Jerry and Billy were both pretty well covered with burns before very long, and neither of them was happy about it. They were also getting redder and redder from all the heat in the vault, and sweat was literally running down them like cataracts. They were drinking water by the gallon, but it wasn’t enough; they were both losing moisture, and Jerry in particular could actually be seen losing weight. His red skin hung more and more loosely on his frame, and his face was drooping as though it were made of wax. Even Billy was wearing down, and I wouldn’t have believed that possible.

But failure didn’t enter anybody’s conversation until shortly after midnight, when Jerry came out of one of his five-minute sessions in the vault, handed the laser to Billy, and came plodding moistly over to say to Phil, “I don’t think we’re going to make it.”

“What?” Phil brushed it away at once. “Sure we’ll make it,” he said. “You’re tired, sit down a while.”

It was over an hour later, after one o’clock, when Billy for the first time said that it wasn’t going to happen. “We didn’t hit that other wall yet,” he said to Phil.

“We’ll hit it any minute,” Phil assured him.

Billy shook his head. “We won’t hit it at all,” he said. “We’ll never get through this first wall.” Then he turned and went back inside and took his five minutes.

Between one and two, Phil and Joe gave Billy and Jerry frequent pep talks, which had no effect that I could see, and Eddie drifted back every once in a while to comment to the world at large that he didn’t believe in aborting missions.

As for me, I kept quiet for some time, but eventually it seemed to me I had to start taking some sort of stand, so at the end of one of the pep talks I said to Phil, “You know, it’s almost two o’clock now, and we still aren’t out of this vault, much less into the other one. And we agreed we couldn’t stay after five.”

“They’ll make it,” Phil told me.

I didn’t say anything that time, but twenty minutes later when we had essentially the same conversation I said, “They won’t make it, Phil. We’re just wasting time here, and making those two guys work harder than they have to.”

“We won’t quit,” Phil said.

But we did. Jerry came out at three o’clock, gasping and weaving back and forth, and though Billy held his hand out for the laser Jerry walked right on by him, carried it over to where Phil was sitting at the desk, and dropped the laser onto the desk in front of him. “You do it,” he said.

Phil just looked at him. It was hard to tell with the mask, but I think he was just bewildered, couldn’t think of a thing to say.

“I’m not doing any more,” Jerry said. “And neither is my buddy here. You do it.”

“If there’s a problem—”

“There’s a problem,” Jerry told him. “Go on in and take a look.”

So Phil went in and took a look, and when he came out he seemed very shaken. “All right,” he said. “So it didn’t work out. We got half the dough.”

We’d had possession of half the dough by six o’clock, nine hours ago, which neither I nor anybody else pointed out. Maybe because we were all too tired.

So. Jerry and Billy wearily dressed themselves, while Joe tied and gagged the four prisoners under the watchful gun of Phil. I began carrying liquor store cartons of money up to the front, where I got to be the one to inform Eddie that we were aborting the mission. “I knew we should have held onto those hand grenades,” he said. “Always prepare for the unforeseen, that’s the way to run a successful operation.”

By three-fifteen we were out of the bank. The cartons were in the typewriter truck, which Joe and Phil and I traveled in to the Dombey house. We unloaded the cartons into the basement, the Vasacapa corridor, and as we were finishing Jerry and Billy and Eddie showed up in a car they’d just stolen for the purpose. Joe took the typewriter truck away to return it, Phil took the stolen car away to dump it, and the rest of us crawled through to the gym in the prison, leaving the cartons in the Dombey basement.

And that’s how I helped to rob a bank.

44

The two months following the robbery were completely uneventful, which I found startling. I was now a bona fide graduate bank robber, a hardened criminal, no stranger to guns and violence; and yet I was completely the same. And so was the world around me, the pattern of prison and tunnel and apartment and Marian, all exactly as it was before.

Except that my financial problems had been relieved. I’d been eating into the three thousand my mother had sent me, pretending to commit stings now and again to explain where my cash was coming from, but that money couldn’t last forever. Particularly once I had an apartment of my own, and a girlfriend. Now, with an additional nine thousand in the kitty, I might even make it through the two years till parole.

Yes, nine thousand. We’d been hoping for a top of a hundred fifty thousand from the two banks, but of course we’d only managed to rob the one. Luckily, our half-accomplishment had been at the high end of our estimates. Just under seventy-three thousand dollars had been carried out of Fiduciary Federal in those liquor store cartons; divided equally among eight men it came to nine thousand one hundred twelve dollars apiece.

Not bad for one night’s work. That’s one way to look at that number, as my fellow conspirators did. Pretty goddam small pickings to risk a life sentence for, that’s the way I looked at it. I just didn’t have the proper criminal attitude.

Nevertheless we’d done it, and apparently we’d gotten away with it. Marian had no idea I’d been involved in the big bank robbery — the most exciting crime in Stonevelt’s history — and I saw no reason to burden her with the knowledge. As to Joe and Billy and the rest, now that the robbery had actually been performed they were all as calm and gentle and easygoing as well-fed horses. And lazy. Despite their sudden wealth, most of them hardly took a turn outside the prison at all for a while, meaning much more opportunity for me to be out; having to return every damn day for breakfast and dinner was becoming an annoyance, in fact.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Help, I Am Being Held Prisoner»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Help, I Am Being Held Prisoner» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Help, I Am Being Held Prisoner» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.