Дональд Уэстлейк - Help, I Am Being Held Prisoner

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Дональд Уэстлейк - Help, I Am Being Held Prisoner» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1974, ISBN: 1974, Издательство: M. Evans, Жанр: Иронический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

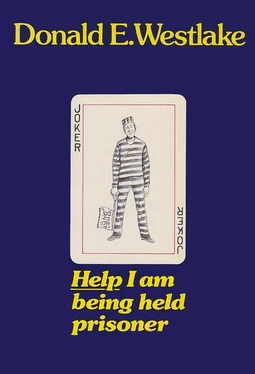

- Название:Help, I Am Being Held Prisoner

- Автор:

- Издательство:M. Evans

- Жанр:

- Год:1974

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-87131-149-8

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Help, I Am Being Held Prisoner: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Help, I Am Being Held Prisoner»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

In the jail he meets seven tough cons with their own private tunnel into the prison town, making them the world’s first prisoner commuters.

Help, I Am Being Held Prisoner — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Help, I Am Being Held Prisoner», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“You won’t see your garden here come up.”

His smile shifted a bit more, but he said, “That’s all right, Harry. I know how I planted it in the fall. I can see it in my mind’s eye. I’ll know when it’s growing, and what it looks like.”

“I’ll get somebody to take a picture of it,” I said, “and send it to you.”

“Thanks, Harry,” he said.

My harping on the garden like that was, I must admit, only partly caused by my sympathy for Andy. His removal also, of course, meant that I wouldn’t be transferred from the gym in the spring to be his gardening assistant; the eviction of Andy Butler had saved for me the life I’d been constructing for myself, and though I truly did feel very badly for him, I must admit I also wallowed somewhat in my own sense of relief.

Then there was the ongoing bank job. The next date for its launching was Friday, the twenty-fifth of February. This was the sixth try at robbing those two banks, and in my conversations with the others it seemed to me the general consensus of opinion had divided itself into two camps: those who were dogged and fatalistic, and those who were ready to forget it and go think about something else. Phil was the captain of the dogged ones, and Max was the most outspoken of the defeatists, with the rest of us more or less raggedly lined up behind one or the other.

Eddie Troyn was strongly on Phil’s side, of course, he being a man who had already expressed his belief that one never aborts the mission. Billy Glinn was also with Phil, but in his case I think it was because his attention span was so short that he wasn’t truly aware of the grinding frustration of all this to the same degree that the rest of us were.

On the other side, Jerry was almost as big a quitter as Max, and I also permitted myself a statement from time to time doubting the wisdom of persisting in the teeth of all these indications of a jinx on the job. Neither Bob Dombey nor Joe Maslocki would ever allow themselves to be pinned down to an opinion on the subject, but public opinion believed that Joe leaned toward Phil’s point of view and that Bob leaned toward Max.

Which left us split down the middle, four and four. But even if it had been lopsided, if it had been seven against one, with Phil the only one wanting to go on, I believe that his determination, his bulldog refusal to let go, would have carried the day just the same. Phil was going to rob those banks, he’d decided to rob them, and he was damned if anything was going to stop him.

I must admit I did do some idle thinking from time to time about providing Phil Giffin with the kind of accident he’d once considered for me. But I’m not a violent man by nature, particularly against somebody as all-around frightening as Phil Giffin, so I did nothing.

And February 25th arrived. That was all right; I was prepared. Earlier in the day I had made my visit to Western National, the other bank, and left my two little packages in wastebaskets there.

More bombs, yes, but not stink, not this time.

Smoke.

When, at five past five, the billows, the clouds, the profusions of thick black smoke began dribbling from every nook and cranny of that pseudo-Greek temple, when the ten-foot-high gold-painted metal front door was thrown open by a coughing wheezing guard, followed by an unrolling sail of cloud that came beating out of that bank like the ghost of one of those tanks out at Camp Quattatunk, and when, in addition, the distant sound of sirens was heard yet again, coming this way, Phil did not lose his temper. No, he did not.

What he did, he got to his feet, slowly, deliberately. He stood next to the table, looking straight out through the luncheonette window at the shimmying wall of smoke now obliterating the entire other side of the street, and in a quiet, calm — yet grim — voice he said, “I am going to get those banks. I’m telling you, and I’m telling those banks, and I’m telling God and all the saints, and I’m telling anybody who wants to hear it. I’m not giving up. I’m going to be here twice a month, every month, for the rest of my life if it takes that long, and you fucking people are going to be here with me, and those fucking banks are going to be waiting over there, and one of these times, I’m going to rob those two banks. I’m going to do it.”

Saying which, he left, and went straight back to jail, and stayed in his bed for the next three days. But we all knew that on Monday, the fourteenth of March, we would be back in that luncheonette.

And, apart from my growing terror of Phil, I had run out of tricks again.

37

And besides that, another of those damn ‘help’ messages showed up.

With the advent of Marian and the apartment, I had been choosing mostly to spend nights off the reservation, covering for other members of the group who were away during the day. So I was in the mess hall for lunch that day, and it was at lunch that it happened. Since the call went out immediately, and rather urgently, for me to get my ass over to the warden’s office, it’s just as well I was present in prison at the time.

Warden Gadmore, when Stoon escorted me into his office, was looking very annoyed, though it was impossible immediately to tell whether he was annoyed at me or at the large plastic shampoo bottle dribbling vegetable beef soup down its sides onto the surface of his desk. I knew it was vegetable beef soup because I’d just had some for lunch, ladled out to me from one of the big vats they used on the serving line in the mess hall.

It turned out the warden was annoyed at us both. Glaring at me, he said, “Do you know what day this is, Künt?” Annoyed or not, by God, he pronounced my name right.

It was Monday, the seventh of March, and after a brief hesitation I told him so. He nodded, and through his annoyance he affected sadness; but I knew he was really just annoyed. The sadness was rhetorical. “It is just two months and two days,” he said, “since I gave you your privileges back.”

I had been worried when Stoon arrived to bring me to the warden’s office, but I had tried to thrust fear away; after all, I hadn’t done anything the warden could know about.

But someone else could have. I had deliberately avoided thought of the ‘help’ messages on the walk over, but now I knew the worst had happened. Feeling a cold inevitability, I said, “There’s been another message.”

“Very funny, Künt,” he said, and gestured at the shampoo bottle. “It really does have its comical side, I must admit.”

“I don’t know what you mean, sir,” I said.

“I mean the bottle found floating in the vat of vegetable beef soup,” he said. He thrust a tattered piece of brown paper at me. “With this message in it!”

The same old message, scrawled this time with pencil on a wrinkled torn-off piece of a brown paper bag. I said, “The message was in the bottle?”

“By God, Künt,” he said, “you are either a consummate liar or you have an imitator somewhere in this prison. I wish to God I could read your mind.”

“So do I, sir,” I said, thinking only of my innocence in connection with the message in the bottle. But almost immediately I thought of what else the warden would find in my head if he happened to look there, and I felt an incipient twitch in my cheek.

No no! If I started blinking and twitching and scratching he’d never believe me! To distract myself, not caring whether I was protesting too much or not, because the important thing was to regain self-control, I said, “Sir, if you could see inside my head you would find that I haven’t performed one single practical joke since last December, since before you took away my privileges.”

I said that in all sincerity, too, and I meant it, regardless of the things I’d done to the typewriter repairman’s truck, and regardless of the smoke bombs in the Western National Bank’s wastebaskets, and regardless of the bomb threat phone call to Fiduciary Federal Trust. Those had not been practical jokes. They had been practical, in the sense of useful, but they hadn’t been jokes. No, they had been deadly serious.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Help, I Am Being Held Prisoner»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Help, I Am Being Held Prisoner» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Help, I Am Being Held Prisoner» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.