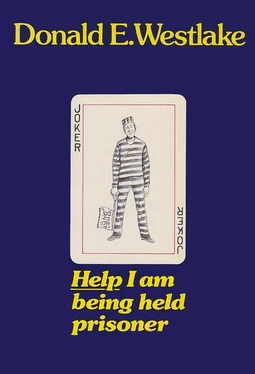

Дональд Уэстлейк - Help, I Am Being Held Prisoner

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Дональд Уэстлейк - Help, I Am Being Held Prisoner» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1974, ISBN: 1974, Издательство: M. Evans, Жанр: Иронический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Help, I Am Being Held Prisoner

- Автор:

- Издательство:M. Evans

- Жанр:

- Год:1974

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-87131-149-8

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Help, I Am Being Held Prisoner: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Help, I Am Being Held Prisoner»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

In the jail he meets seven tough cons with their own private tunnel into the prison town, making them the world’s first prisoner commuters.

Help, I Am Being Held Prisoner — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Help, I Am Being Held Prisoner», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

He truly did have a problem. He didn’t have a Social Security number, so far as he knew, and had never heard of Medicare until I mentioned it; would either of those pay his dental bills? He had no family or friends on the outside, no skills other than packaging license plates, nowhere to go and nothing to do. Even with his teeth his prospects would have been bleak.

He insisted they were pushing him out only because the prison was overcrowded, but I believed that what had happened to him was simply some horrible misapplication of man’s humanity to man. I was convinced some official somewhere was delighted with himself for rescuing Peter Corse from oblivion and sending him out into the world again with no hope, no future, no family and no upper plate.

I did sympathize with him. I offered to write a letter for his signature to his Congressman — I couldn’t write mine, he being one of the two in the accident that had brought me here — protesting the situation, but he refused. He came from that last generation of Americans who would rather die than ask anybody for anything, and he was determined to keep his toothless integrity to the end. He spent much of his time muttering and grumbling dark threats about how he would get back in here one way or another, but they didn’t mean much. What could a man in his age and condition do, really?

We only had a week together, but in that time we became fairly good friends. It made him feel better to have somebody he could complain to, who would neither laugh nor ignore him. He also liked playing the role of the old pro, showing the new boy the ropes. He’d developed simple cleaning and storing rituals in his cell over the years to make life easier for himself, and I adopted them, every one. On the yard he introduced me to some of the other older cons, including the gardener I’d watched through Warden Gadmore’s window. Butler, his name was, Andy Butler, and up close he had masses of thin white hair, a round nose, and a simple beautiful smile; I wasn’t surprised when Corse told me Butler traditionally played Santa Claus in the prison Christmas pageant.

Corse also told me which cons to stay away from. There were three groups of tough guys on the yard that I should avoid, and there were also the Joy Boys. This last bunch never caused trouble on the yard, but they had made the shower room their personal territory on Mondays and Thursdays. “Never never take a shower on Monday or Thursday,” Corse told me, and rolled his eyes when he said it.

At work, too, Corse was my Virgil. It was his job I was taking, and during the week which was his last and my first he showed me how it was done. It was a simple job, but satisfying in its way. I was to sit at a wooden table, with a stack of thin paper envelopes on my left and a stack of just-painted license plates on my right. In front of me I had a rubber stamp like a supermarket price marker and a stamp pad. I would take the top two plates from the stack, check them to be sure they were both the same number and that the paint job had been properly done, and then insert them together into an envelope. I would then adjust the rubber stamp to the same letter-number sequence as the license plates, wump it onto the stamp pad, wump it onto the envelope, and toss the package of plates and envelope onto the far side of the table in front of me, where a rawboned tattooed man named Joe Wheeler would check the number off on his packing list and put the plates into a cardboard carton, ready to be sealed up and shipped out to the Motor Vehicle Bureau in Albany.

There was a strangeness about the week I shared with Peter Corse. He had been here thirty-seven years, prison had freeze-dried the juice and the life out of him — like a cancer victim frozen after death to await a cure — and now he was leaving. And I had arrived, to take over his cell and his job and his relationships with his old cronies. I’d been looking forward to the new life I’d lead in prison, but this was maybe going too far.

Corse always kept his lower plate in a glass of water under his bunk while he slept, and the night before he left I hid it in the foot of the bed. When he found it he would think he’d left it in his mouth last night, lost it in his sleep, and that it had traveled to the other end of the bed because of his movements while asleep.

Except that he didn’t find it. I can’t think why not, it wasn’t hidden that well. He was frantic when he got out of bed, of course, but he was poking through his blankets when I left for my license plate job and I assumed he’d have his teeth back in his head in just a few minutes.

That night, however, when I transferred to his bunk, the lower plate was still there. That made me feel bad for a while — particularly because this was the kind of thing I was trying to stop doing — but after all half a set of teeth hadn’t been that useful to him. He was better off starting from scratch than trying to suit a civilian upper plate to these institutional monstrosities.

4

After three weeks my job was changed. A guard named Fylax, who disliked me in a brooding sullen way, called me out of line after breakfast and told me not to report to the license plate shop any more, but to get over to the gym at ten o’clock. “You’ve got a new job,” he said.

“Thanks.”

“Don’t thank me. A whole lot of us tried to talk the warden out of giving you anything at all.”

I didn’t understand that attitude; I hadn’t done anything to anybody since I’d been here, except for Corse’s teeth and the warden’s doorknob and a little business with pepper in the mess hall on two occasions. Nothing that could be traced to me. Fylax had simply chosen to dislike me, that’s all. Who all those others were who had talked against me to the warden I didn’t know, but I suspected they existed principally in Fylax’s mind.

Though maybe not. At the gym I had to report to a trusty named Phil Giffin, and he laid eyes on me. “I don’t know where you think you get off,” he said, giving me an angry look from under thick black brows. “This is a goddam plush job. It isn’t for new fish, and it isn’t for short timers, and it isn’t for cons outside our own group.”

I was all three, a new fish and a short timer and a con outside Giffin’s own group. Looking apologetic, I said, “I’m sorry, I didn’t ask to change. It just happened.”

“It just happened.” He stood frowning at me, a wiry narrow leathery man with a cigarette smoldering in the corner of his mouth, and I suddenly realized I’d seen him several times out on the yard. He belonged to one of the groups Corse had warned me against.

I said, “I’ll ask for my old job back. I don’t want to be in the way.”

I found out later he’d been trying to decide whether or not breaking my legs would be the best way to solve the problem. If I were to spend two or three months in the hospital, his group could arrange for someone they approved to take my place here. But for reasons that had nothing to do with me and everything to do with not making himself and the gym overly noticeable, he finally shrugged and said, “Okay, Kunt, we’ll try you out.”

“Künt,” I said. “With an umlaut.”

But he had turned away, heading off across the gym floor, and I moved quickly to catch up with him.

There are monetary seasons of thaw and frost in institutions dependent on government funds. During a rich thaw ten or so years ago, this gymnasium had been constructed on a site formerly outside the prison walls. A number of lower middle class homes had been condemned, purchased by the state, razed, and the gym put up in their place, tied in at one end with the original prison wall. It was a huge structure containing three full basketball courts, a warren of offices and locker rooms and shower rooms, and an extensive supply area filled with sports equipment, but with no windows anywhere except in the wall facing the rest of the prison compound. It was like being in some converted nineteenth-century armory; I half expected show horses to appear, practicing their drill routine.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Help, I Am Being Held Prisoner»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Help, I Am Being Held Prisoner» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Help, I Am Being Held Prisoner» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.