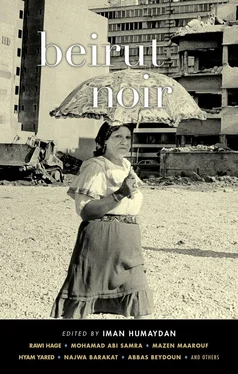

Muhammad Abi Samra - Beirut Noir

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Muhammad Abi Samra - Beirut Noir» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2015, ISBN: 2015, Издательство: Akashic Books, Жанр: Детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Beirut Noir

- Автор:

- Издательство:Akashic Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2015

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-1-61775-344-2

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Beirut Noir: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Beirut Noir»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Most of the writers in this volume are still living in Beirut, so this is an important contribution to Middle East literature — not the “outsider’s perspective” that often characterizes contemporary literature set in the region.

Beirut Noir — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Beirut Noir», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Months had passed with her staying with me at my parents’ house. On the evening of the invitation, I intentionally put on a long sky-blue dress whose thin cloth revealed my body’s curves. When I opened the door to them, I swallowed laughter upon seeing a pile of jet-black hair on the director’s head. I welcomed them and brought them into the living room, congratulating the director on his new hair, but I surprised him and myself by saying to him, with a smile, that his baldness used to entice me. He stared silently at my face for a moment before moving his gaze onto my body and stabilizing it at the tops of my thighs, and I asked him if he liked my dress. My friend answered that the dress — her dress — was more beautiful on my body than her body, saying to the director, “Look, look, isn’t she just like Mary Magdalene — why don’t we use her as a drawing model at the institute?” Then she turned on the large crystal chandelier hanging from the high ceiling, and the lights of its many lamps were diffused throughout the expansive living room. I wanted to say that women’s bodies seem bald when they are free of clothes, but I turned quickly toward the door of my room, explaining that I would change the dress I was wearing for another one. The director mentioned that we were alone in the house, that no one among us was a stranger, and that his wife wore a red dress like mine after she went into the hotel room and took off her white wedding gown. I nodded and headed toward a seat in the living room. But I quickly stopped, since a new scene suddenly loomed in my imagination: the director on a bed in a hotel room, tearing a see-through red dress off the body of a woman. It then occurred to me that I was the woman whose dress was ripped off on the bed, here in my room, after my friend had left at the end of the evening.

Originally written in Arabic.

The Death of Adil Uliyyan

by Abbas Beydoun

Ras Beirut

The café was almost empty. Two men were sitting at a corner table playing cards with unusual silence for a game around which crowds of spectators usually gather and work their tongues. They seem to be playing more from boredom than anything else, faced with empty tables and pervasive silence. I sat down and after a while one of them, a young, khaki-clad man, approached me. As he walked over, I could make out that he was older than I had suspected from a distance. He shook my hand and asked me what I wanted. When I ordered tea, he told me that the water had been cut off since the morning and it would be better to order a Pepsi. I agreed, in order to avoid further conversation, but the man kept standing right there in front of me, not moving. He stared at me as though waiting for me to recognize him. Then he told me that he knew me. He said he was Samir Uliyyan, the son of Adnan — Adil Uliyyan’s brother — who had apparently told them a lot about me; I am Jahal Mazhar. He told me that Adil had come back from Beirut ill, that they had found something in his stomach. I asked him where Adil Uliyyan was living, and he said that he had built a place in Rweiss, on some land he had bought there.

I didn’t meet Adil Uliyyan until we’d both moved to Beirut. I’d moved here before him, to attend the American University. I rented a house and settled down in the city. But I’d heard what had happened to him in Beirut and most of it was what I would have expected: cruel machinations and scams. He traded in elections. He’d go up to a village and choose a candidate who he was convinced could be the victor. He’d use his influence over certain officials, telling them he had to have a certain amount of money. It’s not important what the ballot boxes said plainly the morning of the elections, he would capture the amount needed to win, then disappear. I heard that he’d belonged to influential parties during the war, struggling within them to achieve a certain rank, rallying around and causing trouble until the party leadership got tired of him and kicked him out. But he always found his way to another party, wreaking havoc within it until they too were exasperated with him.

During the war, he was well suited to join in the killing, quickly becoming one of the war’s rising stars. He spent three months in a military training course and returned from it an officer in the Pioneers of the Revolution unit. As a military man, he could do what he liked. He could refuse orders. He could call on anyone he wanted, mobilize people around him. He could also organize big operations: stealing cars and coming away with a diverse fleet; his comrades had a habit of driving these cars wildly and wrecking them, creating excellent parts at low prices afterward. They would also sell furniture from houses they’d pillaged, and extort the rich and influential in exchange for protection.

The war destroyed political parties and organizations; military wings prevailed, as did the logic of war itself. As soon as killing starts, as soon as human life becomes cheap, then everything is allowed. As soon as people acquire the right to annihilate human life, they become lowly gods who consider everything available, and any material possessions as offerings for themselves. They become idiots, using their whole lives to snatch up whatever comes into their hands. They exist only to expand their authority, committing all sorts of transgressions. After the second or third operation they are liberated from any type of self-reflection and start to believe in themselves — of course, most of the time not giving value to anyone else’s opinion. It can’t hold up. From the moment people start to cross lines, thought becomes weak and can’t defend itself. Each individual must build his authority with his own hands, necessitating an increasing number of transgressions.

Adil Uliyyan — according to what I’d heard of him — did this. I heard that he was extremely reckless and killed more people with his own hands than all the rest. He once walked up to a customs officer in the Beirut port and emptied a cartridge of bullets into his head in front of a group of people. From that time on, no one dared oppose him anymore, even his comrades started to fear him like they would a god. He had killed a man in cold blood and he did it for show. His aides completely submitted to him out of fear; in the beginning, their way of thinking united them. Of course, a way of thinking is only useful as an excuse, an empty excuse. What really unites and equalizes people is fear. The one who inspires fear is the master — but this equality is frightening, since no one knows who will be the first to initiate something, who will be the first to transgress. Adil Uliyyan was the first, and it cost him just one murder. From that time on, he profited from everything. A relatively guaranteed sum came to him from every operation; it was protection money from the aggressors, the ones who extorted money through their racket.

One day, fear caused someone to raise a gun and empty it into Adil Uliyyan’s body. The man went into hiding after that. It was said that he had fled to Brazil, but afterward Adil Uliyyan was bedridden and when he recuperated he was no longer himself. He staggered when he walked, his body shaking violently, his limbs trembling. Despite this, the person who shot him didn’t come forward and feared him even in this state. He had no doubt that Adil Uliyyan could still kill him. His disability made him even more terrifying: those trembling limbs could strangle a person, suck out his bone marrow, squeeze his heart. People waited for him to do something but he didn’t budge. In this way, he remained the very image of fear itself. He was fear trapped in a shaking body — his fingers quivering; his two eyes open and ready.

Samir Uliyyan told me that after they found something in Adil’s stomach, he moved from Beirut to Sanawbariyeh to rest there. I didn’t know if I should visit him; it is true that we had been... I don’t know how to put it... friends. I’d meet up with him from time to time, until we both left Sanawbariyeh. We were friendly when we were first becoming men; but we were comrades, nothing more. Every day we’d cross the village together. He was a liar and I wasn’t. He was outgoing and I was shy. But those were the days of our innocence. Even in all his lies and exuberance, Adil was innocent back then. Who would think that an idle lie could transform into a crime? Who would imagine that shyness and indecision could transform into intrigue? But innocence can show through lies, it can show through shyness. It can be idle chitchat, it can boast, it can rave deliriously and go into a coma. No one knows what it will lead to.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Beirut Noir»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Beirut Noir» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Beirut Noir» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.