Muhammad Abi Samra - Beirut Noir

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Muhammad Abi Samra - Beirut Noir» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2015, ISBN: 2015, Издательство: Akashic Books, Жанр: Детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

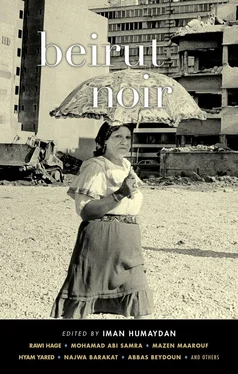

- Название:Beirut Noir

- Автор:

- Издательство:Akashic Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2015

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-1-61775-344-2

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Beirut Noir: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Beirut Noir»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Most of the writers in this volume are still living in Beirut, so this is an important contribution to Middle East literature — not the “outsider’s perspective” that often characterizes contemporary literature set in the region.

Beirut Noir — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Beirut Noir», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

One Tuesday evening, I put all the small wooden boxes in my bag. I climbed up to the roof of the building. The sky was clear and smooth. I smiled, saying to myself, There’s no mucus tonight. We used to consider the clouds a collection of strips of mucus. So I thought: We can choose an endless number of stars so that we can leave some for the next day . I waited for Nazmi. But after many hours, the stars started getting bigger, inflating, swelling up. They became faces. They moved from one side of the sky to the other. I was no longer able to follow how they flowed through the sky. They used to bump into each other like marbles. Giant marbles. And they emitted terrible sounds. They split open the edge of the roof and the flimsy aluminum antennas, which we used to bend on purpose as revenge against the neighbors who treated Nazmi badly when he delivered gas canisters to them. Indeed, even the Ferris wheel at the amusement park started shaking to the right and left like a giant coin. It was lit up. But I didn’t leave. I opened the bag and looked at the boxes. Then I looked again at the stars. I measured them. Lengthwise and then crosswise. From where I was standing on the rooftop. I only used two fingers. That was the latest method I’d discovered to measure the size of the stars.

If Nazmi had been here he would have learned it easily. If he’d been able to hear me, I would have said to him, “It isn’t difficult at all. We do it just like this. It’s like when we close our eyes, like usual. But for this we close only one eye, and the other one we don’t use... We keep it open.” I made a distance between the first finger on my hand — the first thick, short finger — and the second one that we use to point out new places to people. Then I unzipped the bag. I opened my two fingers to the size of a star and the space between them seemed bigger than all the small boxes. I closed the bag right away. I sat on the flimsy edge of the roof. But it wasn’t going to collapse, otherwise I wouldn’t sit there. I started getting sleepy. I dozed off a bit. Then I woke up. The floor where Nazmi lived, in the fifth building on the way down the incline, was not lit up. I kept looking at the half of the apartment where he lived with his family. I could perhaps notice some movement in the kitchen, behind the giant glass doors and the clothesline. I threw a look from where I was to the entrance of the building, but I got dizzy and was afraid to lose my balance and fall. I took out the halawa sandwich that Nazmi and I were supposed to share and devoured it. It was stale. I believed it would help me not to faint. I didn’t leave him even a bite.

The stars were still crashing into each other. And the sound was loud. So much so that people left their houses. They were carrying their belongings and bringing their children out. The police were waiting under the building to be sure everyone left. After a little while my father came, angrily. He slapped me and took me by the hand and emptied the boxes onto the roof. No, it’s not good for my reputation that I accuse my father of that. I’m the one who emptied the boxes. I left the building with him, we left the building together. Me and my father and my mother. My mother was crying too and threatening that she’d make me pay for this later in our new house. I saw a lot of people leaving, emptying their apartments, evicting themselves from the building. They shook hands quickly, then jumped in their cars, revved their motors, and took off without looking back.

There was a car waiting for us as well. I sat next to the window. From my spot, I couldn’t see the half of the apartment Nazmi and his family lived in. I saw the people from the other family who lived in the other half of the apartment. All of them were on the balcony. I wanted to speak to them, I waved at them, but no one saw me. My hand was small and it was dark. Everyone was screaming — the policemen, children, women, the men in the pickup trucks. Everyone. I thought about doing something clever. So clever that no one around us — me, my mother, and my father — could guess. I lifted my head and looked at the stars. They had stopped quarreling. They went back to their natural size. I measured them again with the same new method. And I grew sad. Sad for the small wooden boxes left there. My feeling of sadness soon faded, however. Quickly. With the speed of a star which crashed into its sister. Just as quickly my sadness faded at the thought that Nazmi would come up to the roof after leaving all the people and the police, and he would complete what we had started together. I only hoped that he would close his eyes tight.

4.

After our departure from the building, a rumor started that the police hadn’t come because of the noise of the stars crashing into each other. But rather because of the colonel who lived in the building across the street. People used to hate him and the police who gathered by his house. He was always grouchy. But I doubted this rumor. I’d never seen the colonel harm anyone and I used to sometimes defend him to Nazmi on the roof. I would say, “He probably saw something bad today and he’s grouchy because he’s sad.”

I defended him even though I didn’t need to, and Nazmi would interrupt me, saying, “Why don’t we start throwing boxes?”

Perhaps I said that because I thought I loved his daughter Dalia and thought she’d love me when she grew up. In the morning I would stand behind the window, holding a big mug of hot milk. But I wouldn’t start drinking from it until I saw her come and stand in the window of her own house, across from me. She wasn’t standing behind the window for my sake. But to watch the street, the cars, and the military jeeps waiting for her father down below. She used to watch every idea, person, and cat on the incline except me. Like me, she carried a mug that I always convinced myself also had milk in it. Perhaps this mug had special maramiya herbal tea to treat diarrhea or mint tea to stop her vomiting or some other drink to improve her breath. But I always believed that there was milk in her mug. On the days when Dalia didn’t stand behind the window, I poured my milk out into the potted plants. Their lactose increased daily until they’d become so much lighter you could no longer say that they were green.

I imagined that Dalia lived in a palace. A palace squeezed onto the first floor of the building across the street. Our house was also on the first floor but she never once looked in my direction. In the beginning I thought it was because of the wide street separating our two buildings. I said surely our house is very, very far from the building across the street. I concluded from this that Dalia was younger than me, much younger. That the people, like me, who can cross the street from our building to the one facing it easily take giant footsteps. If you didn’t take giant footsteps you couldn’t see faraway places, like Dalia’s house. Dalia couldn’t see me because of her tiny footsteps and her youth. In order for me to help her realize that she lived near us, in our space with us, the children older than her, I wanted to rename Caracas Hill the Colonel’s Hill.

I asked Nazmi to promote the new name. But he was afraid and warned me, “Perhaps the colonel will get angry, shoot the wooden boxes, and knock them down from above.” Later I learned that Dalia had been sent abroad to a a faraway country with a forest to receive some kind of treatment.

5.

The letter reached me. From Nazmi. It was written on the back of an invoice from the shop. On the back there were a lot of numbers and on the front, words. Two groups. Numbers also have a long life, which we don’t understand at all. Numbers have been breeding and giving birth to other numbers for hundreds of years, though all we do is count them; we believe that when we cross them out, they’re gone. But actually they nest in invoices and walls, heads and files. Most of them are found inside our stores of phenomenal forgetfulness. These stores of forgetfulness fill up every day with new numbers. And the numbers there get to know their relatives that have also been divided for generations. But before they get to these stores they walk close by us most of the time, though we only feel them when they are written down on paper. They decrease when we die and increase if the opposite happens. We also know nothing about their feelings. Or their voices. But then they appear as long as electricity cables, and connect cities and people together. Sometimes they connect two boys. Like Nazmi and me, for example. Even if one of them is lying on his back in a hospital and the other is lying on his back at home. And for this to happen, these two boys lying on their backs must think about the same secret. Even this secret is merely a handful of stars in the sky, where they never saw a wooden box arrive.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Beirut Noir»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Beirut Noir» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Beirut Noir» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.