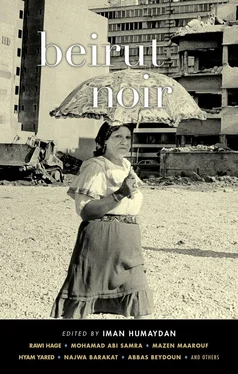

Muhammad Abi Samra - Beirut Noir

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Muhammad Abi Samra - Beirut Noir» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2015, ISBN: 2015, Издательство: Akashic Books, Жанр: Детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Beirut Noir

- Автор:

- Издательство:Akashic Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2015

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-1-61775-344-2

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Beirut Noir: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Beirut Noir»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Most of the writers in this volume are still living in Beirut, so this is an important contribution to Middle East literature — not the “outsider’s perspective” that often characterizes contemporary literature set in the region.

Beirut Noir — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Beirut Noir», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The next Wednesday Hanane doesn’t come, though she hadn’t canceled her appointment. Opening his office door, the shrink finds Hanane’s mother sitting in her daughter’s usual place. He motions for her to enter. The mother shakes her head and hands him a piece of paper. He immediately recognizes Hanane’s list of her life’s 20th of Januaries. This scrap of paper no longer looks like anything. He smoothes it out. A single date has been added to the list. A date before 1992. A January 20th in the year 1985. Next to the year he can read:

Strange body penetrated my body. This isn’t about time, God, or eternity. It is about my father’s dick. When his penis entered my body, time left. That hurt, and then nothing. “A trickle of blood doesn’t matter,” my father said. When I saw victims of the war on TV, that also didn’t matter. Pain is immobile. So are we. Chronos isn’t time. Time isn’t time. Where I am, time is. I kill myself because metastasis is imminent. Cancer is lucidity. Everything hates us. The past. The future. They hate each other. Chronology is nothing but an illusion. We are victims of the compression of nothingness into a notion called time... it’s pain that makes eternity, not time.

Her mother found the scrap of paper next to her daughter’s lifeless body on the day after January 20, 2011. Next to her in bloodred was written: Time doesn’t exist. I cut off its head.

Originally written in French.

Part II

Panorama of the Soul

Beirut Apples

by Leila Eid

Bourj Hammoud

October 10. The tenth day of the tenth month. Hah, oh my God.

10/10... it’s my birthday... What if they came back? Just like that, and walked through this door right now at their real, young ages. Amer, my father; Farah, my mother (I used to joke and tease her when she’d get angry at me and cry, reminding her that her name meant joy ); Amir, Rustum, and Zeina, my siblings — they are bringing me little gifts and a big birthday cake. Would they know me now that I’m older than them? I’d perhaps be a more appropriate father to them now than a brother, even though I was the eldest child. As for Amer and Farah, I’m nearly their age and we’ve become close friends. Who knows, perhaps we’d sit together and reminisce about our childhood and adolescence.

But how would they know my address? And if they knew it, would I even see them? Can the dead come back to life? What if they hadn’t died, and I’d merely imagined this — what if they were alive and remembering me? Do I really want to see them? Do I really want to see anyone? Me — who’s walking terrified, pressed up against every wall on the ship, as if I were a shadow, trying to hide from the apparition of a human, cat, or even a mouse, seeking shelter in the closest container or near a broken lamppost. I wait, trembling and shivering like someone touched by madness.

I didn’t sleep after I heard Amer saying that night, “Farah, Farah, we can’t stay here much longer... Listen to me... we’ve become nothing but live offerings, ready victims, even if they haven’t announced it openly... As soon as one person is killed or kidnapped in the capital, we’ll be the first revenge, the surrogate for unknown blood spilled in a dark and unjust dispute. They killed Samer that night. No one could protect him... They said that five masked men abducted him from his house after they raped his wife in front of him. They showed mercy to his children when they shoved them into the bathroom, threatening to pour cold water on them if they so much as made a single sound. His eldest son was not so lucky, his arm was broken — his siblings heard it crack — when he attempted to scream, calling for help, trying to defend his parents. They were stricken by what seemed like a mute stupor... They executed Samer right there behind the olive press. Jihad, Rameh, and I saw a wet explosion, red splattered on the wall...

“When Nael and his fiancée suddenly disappeared, everyone said they left to elope, they ran off to get married far away because Nael is the neighborhood strongman and the handsome fellow didn’t have the means to pay for the wedding. That’s how he presented Nawal’s parents with a fait accompli. Some people snickered, saying that it all happened with Nawal’s father’s agreement, because he was known for his extreme stinginess — this way he’d be able to escape from the financial burdens of a wedding and the related hospitality... Then the village — though I can no longer say the whole village — was stunned, because it became clear to me and everyone else that the people being killed were all the same kind of people, when the corpses of the couple who’d eloped were found on the way out of Tell al-Qasa‘yin, where no son of Adam — and not even the jackals — dared to pass because of the savageness of the place, its thick, wild plant growth and the poisonous snakes. Then, when Fares was found dead in his orchard under the walnut tree, a labneh sandwich in one hand and a flask of village ‘araq in the other, they said he killed himself, the growing season is sparse this year. Fares couldn’t bear the brunt of his debt and all this loss so he killed himself... His pruning clamp was leaning cold and sad against the tree trunk, wishing it could utter a testimony of truth for its old friend... It was also said that Hani drowned in the lake, he wasn’t good at swimming, he’s been afraid of water since his childhood. He used to get a beating and then he’d go take a bath, according to what his mother said... His comrades weren’t able to rescue him, the boat was getting farther away and then gave out when they tried to return to help him... Who can utter a tale different from all the others, which rationalizes the tragic departure of these souls?

“What secret word, my Farah, is being spread through the alleys, houses, gardens, pools of water, and winds, preventing everyone from having funerals, reporting, and making complaints? Need I spell things out for you, telling you more stories of their mysterious disappearance? Their disappearance drenched with the mercilessness of a forcible death, their torture and execution, only because they belong to a particular sect, to a sect and its presumed thought, a kind of classification as it becomes a strange new identity, no longer having the right to exist here among a different majority group. How do they appoint themselves the gods of the new era, controlling the destiny of innocent people and ending their lives in this way, tearing them up by their roots and throwing them away like the weeds that grow around the edges of ancient balconies? By what right... by what right...? Should I tell you more? Should I recite to you the mythical conversation I had with the ghosts of these corpses? How they visit me in dreams when I’m sleeping and then I can’t sleep anymore... We have to leave, I can’t tolerate the thought of any kind of harm coming to you and the children, I can’t stand the thought of our family ending like this... We must leave as soon as possible. Tomorrow is better than later... Tomorrow we’ll leave for Beirut...”

“Oh Amer, the war is at its fiercest over there. That’s what we see and hear on the news every evening. It shows guns, bombs, destruction, and murder everywhere,” I heard Farah saying in a low voice.

But Amer cut her off before she could continue: “If we die over there they’ll know us, give us a funeral, and bury us — not throw our corpses to the monsters without even saying a prayer.”

“ What harms the sheep after it’s flayed? Isn’t that what you said once...? If we die we’re dead. Isn’t that true, Dad?” But of course Amer didn’t hear me.

W-e w-i-l-l l-e-a-v-e for B-e-i-r-u-u-u-u-u-u-u-t... We will leave for Beirut... W-e w-i-l-l l-e-a-v-e... B-e-i-r-u-t... The sentence rang in my ears and my head like the loud, irritating howl of a car horn... Exactly like the horn of Bahjat’s car, he’s the most famous show-off in our village. We will leave for Beirut. How, when I am a son of the plains and natural springs? I am a child of the hills and the little valley, I truly delight in being a shepherd, taking care of goats, cows, and sheep. To whom will I leave the sky here, as I’m the guardian of the dust-covered mountain, whose color is that of our newly born foal? In my heart, I carry the secrets of the clouds and the melting snow on the peaks. I entrusted to the river a song that would make every grain of wheat — and every pomegranate and fig tree — grow, a song for the orphaned walnut tree on the roof of our house and for the grapevines.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Beirut Noir»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Beirut Noir» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Beirut Noir» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.