“All right, it’s stupid. But that’s the way it is. So just drive toward the river.”

The car moved faster. It came onto Wharf Street and he told her to turn north. They went north for several blocks and presently he told her to park up ahead. He pointed to a wide gap between the piers. It was a grassy slope, slanting down to the water’s edge.

It was mostly weeds and moss, not much more than a mud flat, and during the day it was nothing to see. But under the moon it was serene and pastoral, the tall weeds somehow stately and graceful, like ferns.

“Very pretty,” she murmured. “It’s nice here.”

“Well, it’s quiet, anyway. And there’s a breeze.”

For some moments they didn’t say anything. He wondered why he’d directed her to this place. It occurred to him that he used to come here when he was a kid, coming here alone to feel the quiet and get the river breeze. Or maybe just to get away from the shacks and the tenements.

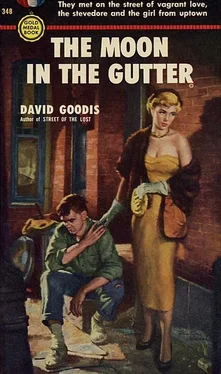

He heard her saying, “It’s so different here. Like a little island, away from everything.” Then he looked at her. The moonlight poured onto her golden hair and put lights in her eyes. Her face was entrancing. He could taste the nectar of her nearness.

He told himself he wanted her, he had to have her. The need was so intense that he wondered what kept him from taking her into his arms. Then all at once he knew what it was. It was something deeper than hunger of the flesh. He wanted to reach her heart, her spirit. And his brain seethed with bitterness as he thought, That ain’t what she wants. All she’s out for is a cheap thrill.

The bitterness showed in his eyes. He spoke thickly. “Start the car. Let’s get away from here.”

“Why?” She frowned slightly. “What’s wrong?”

He couldn’t look at her. “You’re just fooling around. Having yourself a good time.”

“That isn’t true.”

“The hell it isn’t. I been around enough to know what the score is.”

“You’re adding it up backward.”

“Am I?” He glowered at her. “Who do you think you’re kidding?”

She didn’t say anything, just shook her head slowly.

He pointed to the key dangling from the ignition lock. “Come on, start the car.”

She didn’t budge. Her hands were folded loosely in her lap. She looked down at them and said quietly, “You’re not giving me much of a chance.”

“Chance for what?” His voice was jagged. “To play me for a goddamn fool?”

She looked at him. “Why do you say these things?”

“I’m only saying what I think.”

“You sure about that? You really know what you’re thinking?”

“I know when I’m being taken. I know that I don’t like to be jerked around.”

“You don’t trust me?”

“Sure I trust you. As far as I could throw a ten-ton truck.”

She smiled again, but there was pain in her eyes. “Well, anyway, I tried.”

He frowned. “Tried what?”

“Something I’ve never done before. It isn’t a woman’s nature to do the chasing. Not openly, anyway. But I knew it was the only way I could get to know you.” She shrugged. “I’m sorry you’re not interested.”

His frown deepened. “This on the level?”

She didn’t reply. She just looked at him.

“Damn it,” he murmured, “you got me all mixed up. Now I don’t know what to think.”

She went on in a tone of self-reproach, “I tried to be subtle. Or clever. Or whatever it was. Like today on the docks, when I used the camera. But deep inside myself I knew the real reason I wanted your picture.”

He looked away from her.

She said very quietly, “I wanted to keep you with me. I had to settle for a snapshot. But later, when I left the camera on the table, I was strictly a female playing a game. What I should have done was say it openly, bluntly.”

“Say what?”

“I want you.”

He could feel his brain spinning. He fought the dizziness and managed to say, “I’m not in the market for a one-night stand.”

“I didn’t mean it that way. You know I didn’t mean it that way.”

For some moments he couldn’t speak. He was trying to adjust his thoughts. Finally he said, “This is happening too fast. We hardly know each other.”

“What’s there to know? Is it so important to find out all the details? The moment I met you, I felt something. It was a feeling I’ve never had before. That’s all I want to know. That feeling.”

“Yes,” he said. “I know. I know just what you mean.”

“You feel it too?”

“Yes.”

They sat there in the bucket seats of the MG, and the space between the seats was a gap between them. Yet it seemed they were embracing each other. Without moving, without touching her, he caressed her eyes and her lips, and heard her saying, “This is all I want. Just this. Just being near you.”

“Loretta—”

“Yes?”

“Don’t go away.”

“I won’t.”

“I mean, never go away. Never.”

She sighed. Her eyes were closed. She murmured, “If you really mean it.”

“Yes,” he said. “I want this to last.”

“It will,” she said. “I know it will.”

But it wasn’t her words that he heard. It was like soft music drifting through the dream. And the dream was taking him away from everything he’d known, every tangible segment of the world he lived in. It took him away from the cracked plaster walls of the Kerrigan house, the noises of the tenants in the crowded rooms upstairs, the yelling and bawling and cursing. It took him away from the raucous voice of Lola, and the empty beer bottles cluttering the parlor, and his father snoozing on the sofa. And in the dream there was a voice that said good-by to Tom, good-by to the house, good-by to Vernon Street. It was a murmur of farewell to the tenements and the shacks, the thick dust on the pavements, the vacant lots littered with rubbish, the yowling of cats in dark alleys. But there was one dark alley that refused to accept the farewell. Like an exhibit on wheels it came rolling into the dream to show the rutted paving, the moonlight a relentless lamp glow focused on some dried bloodstains.

His eyes narrowed to focus on the kin of the number-one suspect.

His voice was toneless. “Tell me something.”

But he didn’t know how to take it from there. It was like a tug of war in his brain. One side ached to hold onto the dream. The other side was reality, somber and grim. His sister was asleep in a grave and she’d put herself there because a man had invaded her flesh and crushed her spirit. He told himself he had to find the man. Regardless of everything else, he had to find the man and exact full payment. His hands trembled, wanting to take hold of an unseen throat.

She was waiting for him to speak. She sat there smiling at him.

He stared past her. “You like your brother?”

“Very much. He’s a drunkard and a loafer and very eccentric, but sometimes he can be very nice. Why do you ask?”

“I been puzzled about him.” He looked at her. “I been wondering why he comes to Dugan’s Den.”

For some moments she didn’t reply. Then, with a slight shrug, “It’s just a place where he can hide.”

“What’s he hiding from?”

“From himself.”

“I don’t get that.”

Suddenly her eyes were clouded. She looked away from him. “Let’s not talk about it.”

“Why not?”

“It isn’t pleasant.” But then, with a quick shake of her head, “No, I’m wrong. You have every right to know.”

She told him about her family. It was a small family, just her parents and her brother and herself. An ordinary middle-class family in fairly comfortable circumstances. But her mother liked to drink and her father had his own bedroom. She said they were dead now, so it didn’t matter if she talked about them. They had an intense dislike for each other. It was so intense that they never even bothered to quarrel, they hardly ever spoke to each other. One night, when her brother was seventeen and had just got his driver’s license, he took their parents out for a ride. He came home alone with a bandage around his head. The father had died instantly and the mother died in the hospital. Within a few weeks Newton began to have fits of hysterical laughter, wondering aloud if he’d done it on purpose, actually doing them a favor and giving them an easy way out. A bachelor uncle came to take charge of the house but couldn’t put up with Newton’s ravings and strange behavior and finally moved out.

Читать дальше