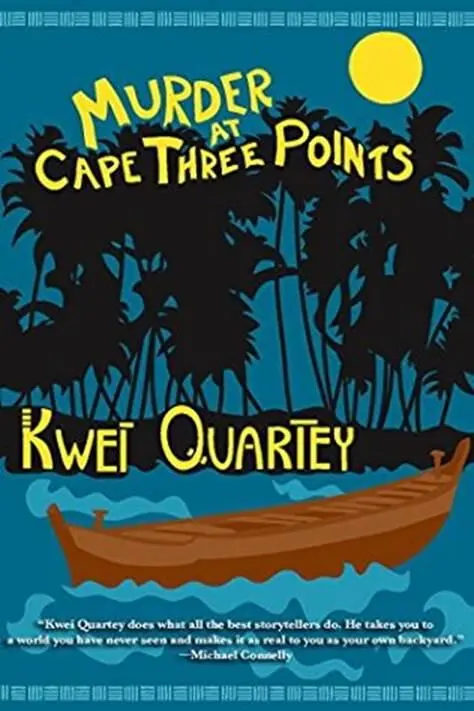

Kwei Quartey

Murder at Cape Three Points

The third book in the Darko Dawson series, 2014

To the people of Cape Three Points,

the land nearest nowhere

Money calls blood

– FROM AN AKAN PROVERB

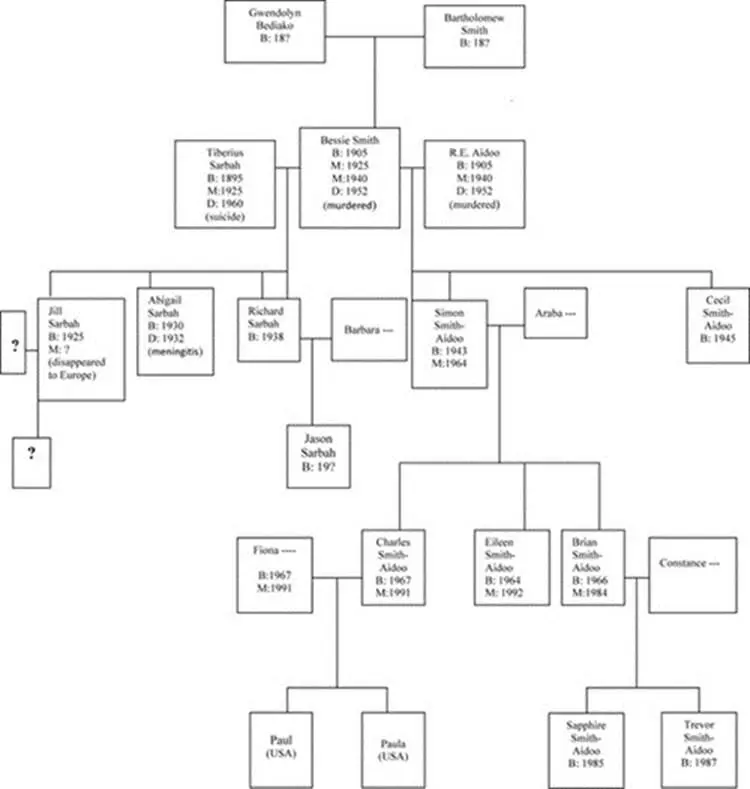

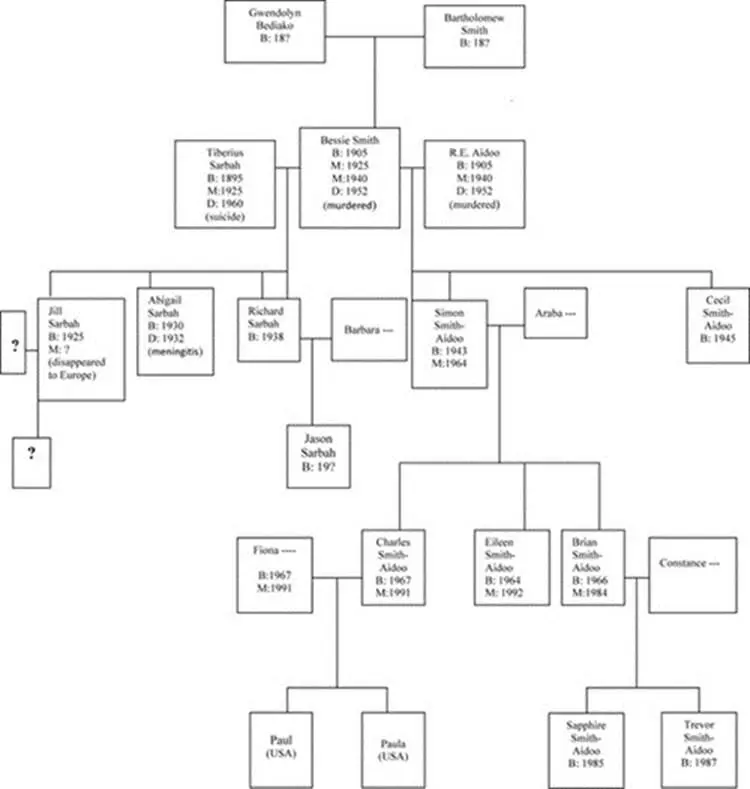

THE SMITH-AIDOO AND SARBAH FAMILY TREE

***

CAPE THREE POINTS, THE southernmost tip of Ghana, is beautiful and wild. Verdant forest covers the three finger-like peninsulas that jut into the Atlantic Ocean. Dizzying cliffs overlook the cyan waters. As waves strike the slate grey rocks and burst into gossamer spray, the roar of the sea crescendos like the sibilant clash of cymbals.

At dusk, the brightness of the sky melts and softens. The dying sun lays a wide band of gold across the sea. A full moon rises and imparts a silver gloss to the dark ocean, silhouetting fishing canoes gliding along silently like ghosts.

The forests and mangrove swamps of the coast are flora and fauna sanctuaries. In the Gulf of Guinea too, wildlife flourishes, but not without threat. Frolicking bottlenose dolphins and humpback whales would do well to avoid an alien creature in their midst. Afloat on powerful, squat limbs, its gangly crane booms resemble tentacles. From the derrick, its drill descends like a proboscis and penetrates the seabed to extract as much oil as possible. The creature is the Thor Sterke.

IN JULY, THE Equator dawn begins with a rosé blush expanding across the horizon. For the Thor Sterke crane operator who has worked graveyard, the lovely panorama is a welcome indication that his overnight shift is almost over. He struggles to remain alert as he lifts the last of the heavy loads from the supply vessel stationed at the starboard side of the rig. He brings up a large bundle of drilling equipment and expertly swings it around to the pipe deck, where two workers stand ready to guide the bundle to its assigned destination.

Over the next twenty-five minutes, the sun rises. High up in his cab, the crane operator has a 360-degree view of the seascape. A flat-decked supply vessel is approaching, a trawler is just visible to the south, and two fishing canoes are coming in from the southwest.

“Fuckin’ fishermen,” he mutters. Fishing canoes are not allowed within 500 meters of the rig. That’s the rule, and yet they violate it all the time. They end up colliding with supply vessels, and their fishing nets sometimes snag on crucial rig installations.

He ignores the canoes as he begins another lift and sling, but at the end of the cycle, he watches them draw closer. Two fishermen are in the larger one, which is fitted with an outboard motor. After a while, the fisherman at the stern starts up the motor and turns the canoe north toward the shore. The smaller canoe is neither motor-powered, nor paddled. It appears to be drifting at the whim of the northeasterly sea currents. The crane operator thinks he can make out a figure in the canoe, but something is odd and still about the craft.

He puts a pair of binoculars to his eyes and searches for the canoe. He jumps with fright as a man’s head comes into the field of vision. It is stuck on the end of an upright pole on the bow. Its mouth is open and the right eyeball has been scooped out. At first, the crane operator thinks it must be an extraordinarily lifelike mask and someone’s sick idea of a joke, but as he shifts the field of view slightly, he sees the decapitated man sitting inside the canoe with ragged, bloody pieces of tissue projecting from the dark gorge in his neck.

The crane operator turns his head and retches violently.

HOSIAH WAS ASLEEP. HIS little chest, wrapped in layers of gauze bandages, rhythmically rose and fell. His 24-hour observation in the Intensive Care Unit had passed uneventfully, and now he was on the step-down ward. Darko Dawson sat at his son’s bedside keeping watch, frequently looking up to check the cardiac monitor on the wall.

He was thankful Hosiah was out of the ICU. It meant he was stable and progressing. Dawson had found the high-tech, intensive care environment overwhelming. To him, the array of machines wasn’t so much a reassurance that every possible body system was under surveillance; it was a reminder that every possible body system could go wrong.

He was aware of a slight soreness in his own chest, as though he too had gone through Hosiah’s cardiac surgery-sympathy pains for the boy who meant everything to him. Dawson felt relief and deep gratitude. He and his wife, Christine, had endured the agony of watching their son slowly deteriorate over the seven years of his young life. Hosiah had been born with a large ventricular septal defect, and his physical condition had progressively worsened as his need for surgery had become more urgent every day. Ghana’s National Health Insurance Scheme only paid for the basics, like anti-malarial drugs. Open-heart surgery was not basic. The fee was far beyond their ability to pay.

Dr. Anum Biney, a forensic pathologist who had worked with Dawson on several murder cases, had called up his friend, the director of the National Cardiothoracic Center. Biney’s personal appeal on Dawson’s behalf had resulted in the approval of the operation for a nominal fee.

Dawson was off from work for ten days. It had not been easy to obtain clearance for temporary leave from the Homicide Unit at the Criminal Investigations Unit, CID, whereas Christine, who was a primary school teacher, had easily secured extended time off from work so she could be with Hosiah until he was well enough to return to school.

Christine had gone down the hall to the washroom. Dawson glanced over to the next bed where a four-year-old boy, also recovering from cardiac surgery, was sitting up in bed working on a coloring book. At the third bed, a nurse was attending to a teenage girl.

This hospital room was semi-private. In the adjacent ward, private rooms existed for those who could afford them. Everyone at this exceptionally well-equipped center had either money or good fortune. Located in Ghana’s capital, Accra, where Dawson and his family lived, the center was the only one of its kind in the entire country. He could not help but think of the multitude of children in Ghana dying from congenital heart disease for lack of medical facilities.

Dawson occupied himself by reading the lead article in today’s Daily Graphic newspaper. The headline was “Malgam Makes New Offshore Find.” Malgam, a UK oil company, had been the first to discover substantial petroleum deposits off the coast at Cape Three Points in Ghana’s Western Region. It had been producing oil at the rate of about 70,000 barrels a day. On an international scale, this wasn’t much, but the plan was to increase it to 120,000 bpd over the next twelve months. Meanwhile, Malgam kept making new discoveries and appeared to be doing very well financially.

The oil find was changing the political and economic landscape of the Western Region, especially in the regional capital, Sekondi-Takoradi, the twin city about 180 kilometers west of Accra. Its unofficial name was now the “Oil City,” and apparently, Ghanaians, foreigners, banks, insurance companies, and hotels were flocking to it. Since one visit to see his aunt when he was a teenager, Dawson had not been back to Takoradi, or “Tadi,” as people affectionately called it. He could only imagine how much the city had transformed in that time.

Читать дальше