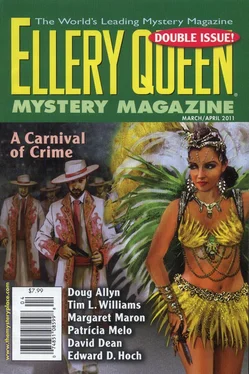

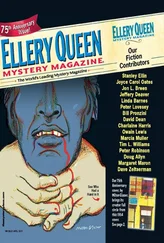

Doug Allyn - Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 137, No. 3 & 4. Whole No. 835 & 836, March/April 2011

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Doug Allyn - Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 137, No. 3 & 4. Whole No. 835 & 836, March/April 2011» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2011, ISBN: 2011, Издательство: Dell Magazines, Жанр: Детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 137, No. 3 & 4. Whole No. 835 & 836, March/April 2011

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dell Magazines

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- Город:New York

- ISBN:ISSN 0013-6328

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 137, No. 3 & 4. Whole No. 835 & 836, March/April 2011: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 137, No. 3 & 4. Whole No. 835 & 836, March/April 2011»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 137, No. 3 & 4. Whole No. 835 & 836, March/April 2011 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 137, No. 3 & 4. Whole No. 835 & 836, March/April 2011», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Not all the other children saw school in the same way. The Garney boys certainly didn’t. For Stephen and Micah, the twins, school was a place to sit with their primer open in front of them and stare at it, their lips twitching a little as if they were reading, but when Miss Collier called on them to recite, they’d startle like they were waking up from a deep sleep, arms jerking out, bony elbows bumping whoever was sitting to the side of them. We learned to shift out of the way when the teacher looked in their direction. But the twins came every day, at least every day that we didn’t see them in back of their house, set at first light to hours of splitting green wood kindling or lifting wet sheets that must have weighed more than they did from the washtub and twisting them through the mangle. The Garneys came to school and didn’t seem to learn much of anything, but it must have felt an easier place than their home. On the winter days when the marks on their faces were fresh and raw, and the cold air when we played Crack the Whip or Fox and Geese would have cut sharp, Stephen and Micah stayed inside, near the wood stove, and stared at the orange flames wavering behind the bars of the little iron door.

When we got home from our rounds, we’d take Patty down along the river and let her graze where she liked, on the stretches of soft, long grasses in the spring, or the summer rushes, then the dry, crackling stems of whatever she could find in the fall. When the snows came, we let her go no further than our yard, for fear of her breaking a leg on a patch of ice, and fed her hay we had bought out of the money she made for us.

We counted it over and over again. Out loud, keeping the total in our heads as we walked from customer to customer, the coins clinking in my pocket. We made a small, tidy stack on the table before we left for school, and again when we got home, carefully adding the day’s count to the paper that we folded and kept in the little box. No one we knew kept money in a bank, no one had enough of it. No one we knew locked their doors. It wasn’t neighbors that posed any threat. Ma would check our addition, and subtraction, when we took money out for hay, and for tithing. The total slowly, achingly slowly, grew. We made no plans for the few dollars in the box in the drawer. We weren’t saving for something special. We saved for the day when a knock came at the door, and everything changed.

So we managed somehow, the three of us together. Ma walked the two miles to the trolley every day except Sunday, took it across Ogden to the laundry, and retraced her path every evening. When she came home to us and bent close as we showed her our homework, she smelled of soap and starch and near-scorched clothes. She always took a book with her, told us she read it on that clattering, swaying ride that set my stomach to churning when we’d go to visit our grandfather, but the bookmark never advanced from morning till night, not until she sent us to our prayers, then sat there at the worn table, reading in the small circle of yellow lamplight.

I don’t know if help was ever offered, and my mother refused just because we were lucky that the house and yard were ours and we could scrape by, or because whatever help might come from my grandfather would be grudging and bitter. He had enough for himself, and what he had he kept. We had taken his son from him, and in his mind, we deserved no more after we lost what he valued most.

The day before it happened, February third, after days of hard snows, we left for school. There had been no new money for Alma and me to count that day, nor had been for weeks. We had dried off Patty as she was due to freshen in March and needed her strength. Mama told us not to worry, that after the calf came there would be plenty of milk, and money from the promised selling. The Mickelbys would buy the calf, if it was a heifer, or the butcher would buy it if it was a bull calf. Alma understood, and contented herself with counting over the same small stacks of coins, a tiny copper and silver fence that only a small child could believe was a guard against disaster. It was harder for me. I missed the early morning milking, when the air was cool even in summer, and the only warm thing was the cow’s body, heat rising from it as I leaned my face and shoulder against her side, and the milk pulsing through her teats warmed my hands.

John Garney shoved past us as we walked, making us stumble. He was muttering, to himself or to the wind, who knew, the words slurred and angry, and the smell of alcohol sharp on his breath. At the corner, where we would always stop and plan our way across with care, for the road sloped and besides the snow that had hardened there into slick ice there were manure piles in various stages of freezing, John — I can call him that, for I am more than twice the age he ever came to be — rushed across and into the path of Harrison’s wagon. Mr. Harrison pulled up his team, but John Garney swore at man and beast and raised his hand to the horses. Earl Harrison was off the wagon before I could blink, and he and John were flailing at each other, then fell and rolled, shouting, on the frozen ground. I pulled Alma back from the road and the men and the stamping, nervous animals. We huddled against the fence of the nearest yard as other men came to the fray and pulled Mr. Harrison off the bleeding and swearing John Garney. He turned over, managed to get onto his hands and knees, swaying, raised his head, and looked at those who had not hurried off, eyes averted. Alma and I were still there, stunned at the public violence between grown men. This was not the norm in our experience. The town was dry, and the hand of the church was heavy. John’s gaze slid over my sister and me and fixed on something behind us.

“You. Come here.” His voice was hard as ice, and the twins, who I guessed had seen near everything of their father’s defeat, went past us as silent as two small figures made of snow. They knew, as did we, what would happen once they helped their father back to their house. But even though they’d bear the brunt of their father’s anger for having witnessed his fall, I believed they would be in school, bruised but stubborn in their quiet staring attention if not to our teacher, at least to the fire dancing in the iron stove. They knew better, I realized later, and Stephen held Micah’s hand in his as they walked to their father. Stephen came alone and would not explain his twin’s, or Jessie’s, absence. Alma and I watched that day and said nothing. What was there to say? Who was there to tell? All we did was sit on the hard bench beside Stephen, silent except for our recitations of that day, the capitals and products of the Mid-Atlantic states, and the conjugations of the verb “to choose.”

I woke during the night, as I had every night since my father died, and turned over and set my hand close to Alma’s mouth to see that she still breathed. Then I walked to my mother’s room, the bare floor cold on my feet, and watched for the slight rise and fall of her shoulders. Satisfied that all was well — as well as it could be, within our house — I wrapped my mother’s green shawl over my nightgown and went to the back porch, slipped on my boots, and went out to check on Patty. The moon was no more than a thin line of light, the snow dull as unpolished silver, and our cow slept in the deep shadows of the shed. As I stood there, watching her breath make little clouds, I heard footfalls on the snow, someone passing through our yard. I looked out and saw a moving shadow, picked out by the light the small figure carried. I must have made some sound, though I meant not to, because he stopped and raised his lantern to see, though it did no more than brighten his face and blind him to me. I was quiet then, and after a few moments he moved on. I watched the light moving away, bobbing as Stephen leaned down to slip through the rails of our fence. So I was not the only one who woke, and walked, though I would not venture as far as he did.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 137, No. 3 & 4. Whole No. 835 & 836, March/April 2011»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 137, No. 3 & 4. Whole No. 835 & 836, March/April 2011» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 137, No. 3 & 4. Whole No. 835 & 836, March/April 2011» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.