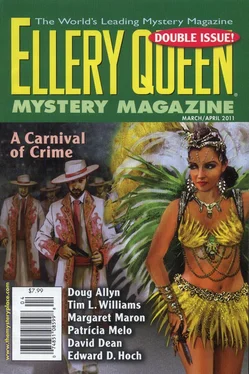

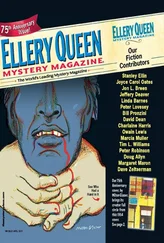

Doug Allyn - Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 137, No. 3 & 4. Whole No. 835 & 836, March/April 2011

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Doug Allyn - Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 137, No. 3 & 4. Whole No. 835 & 836, March/April 2011» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2011, ISBN: 2011, Издательство: Dell Magazines, Жанр: Детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 137, No. 3 & 4. Whole No. 835 & 836, March/April 2011

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dell Magazines

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- Город:New York

- ISBN:ISSN 0013-6328

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 137, No. 3 & 4. Whole No. 835 & 836, March/April 2011: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 137, No. 3 & 4. Whole No. 835 & 836, March/April 2011»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 137, No. 3 & 4. Whole No. 835 & 836, March/April 2011 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 137, No. 3 & 4. Whole No. 835 & 836, March/April 2011», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“The Binary Brothers, I call them. I met them during that crop-circle thing. They’re sweet old guys. Kevin never understood them. He sees the need to be part of something larger as a weakness. Especially if your mind tells you the larger something can’t be true. People used to call that faith. Kevin feels sorry for people like the Happes. I feel sorrier for him. He doesn’t believe there’s any mystery in the world. But every person you meet is an incredible mystery. Kevin can’t see that.

“He thinks he can solve anything with his instruments and gadgets. He’s got infrared cameras out there waiting to record whoever puts the last rock up.”

I asked her how she planned to get around them. She smiled at me in a way that told me I’d missed a clue.

I looked at the map with the colored pins and saw what I should have seen much earlier in the day. Stepping over to the map, I traced the red line with my finger. Then I drew a line from the upper green pin to the center red one and from there down to the lower green one. The pattern was already complete. The pins formed Karnes’s redundant initial, the letter K.

I asked Jones when the professor would spot that.

“Never,” she said. “It would mean admitting that he was wrong. Besides, it’s right under his nose. You never see what’s right under your nose.”

It was the phrase Albert Happe had used. The farmer had been referring to Karnes’s assistant, I now knew. Albert might have thought, as I did, that Karnes was a fool not to have recognized the mystery that was Gennetta Jones.

That wasn’t the safest thought for a married man to have, so I wished her luck with her degree and headed north.

Copyright © 2011 by Terence Faherty

The Backyard Cow

by Trina Corey

Trina Corey debuted in EQMM’s Department of First Stories in March/April of 2009. (See “Vacation.”) The teacher of twenty years lives with her family in northern California and is currently at work on both a new short story and a novel. The following tale arose from her own family history: a great-grandmother who was widowed young, worked in a laundry, and bought a cow to keep in the yard...

We agreed not to talk about it, to each other or to anyone, but she’s been dead for — how is it possible — forty years, and I’m an old lady now, and who pays attention to what old ladies say? So there can’t be any harm in old words about what is lost and forgotten...

Alma and I ate breakfast every morning before there were any lights outside, except the stars and the moon and below them a few lanterns bobbing gold light in the darkness, carried by folks out to do chores or visit the outhouse or heading early to their work. Mama left soon as the sky grayed, every time saying, “Wash the bowls before you go round with the milk,” and, “Watch out for your sister,” as if I needed telling. We scrubbed our faces and hands at the sink, getting rid of every bit of grime. We’d learned more people bought milk from clean children.

Like always, the covered pail was on the bottom step where we’d set it before breakfast, and it took both of us to lift it, the milk sloshing close to the hood, the pail digging into our fingers. The gravel crunched under our bare feet, but we hardly felt it. By the time fall came, we could step on broken glass.

We sidestepped past several houses to the Harrisons’. The honey-colored light from their kitchen poured out onto the little porch, and when we called, “Hello, hello...” Mrs. Harrison came out without making us knock.

“Just set it down right there, girls,” she said. “I’ll get the pitcher.”

Alma unhooked the end of the dipper from her apron and handed it to me without a smile. I’d just started letting her carry it, and she took her responsibility seriously, like she did everything.

“Bless your hearts, girls, bringing us fresh milk every day,” said Mrs. Harrison, holding out the chipped blue pitcher, moving it just enough to keep it under the sometimes wavering stream of milk as I dipped and poured the four cups it took to bring the milk up to the lip. She put the pennies in the palm of my hand one by one, Alma counting them out loud, and I put them in my pocket. I wasn’t ready to share the job of carrying the money with my sister.

The pail was lighter now, but we still carried it together as we turned and went the other way to the Micklebys’ house, and then down the street to the Garneys’. The baby’s crying was loud, like every morning. All the Garney babies cried and cried, and then they stopped and never wept again. Nobody could make a Garney child cry once they grew big enough to decide not to. Even when their father or the worst bully at school caught up with them, they still wouldn’t cry, but just stand there and take it, hands clenched and green eyes burning holes into whoever was whipping them, and when it finally stopped, they’d hand over their lunch or get back to whatever chore they hadn’t been doing good enough. But five minutes or an hour or a day later, whenever they could, they’d run away, like a wild thing to lick its wounds. Maybe they cried where no one could see them, but I doubt it.

When Mama led Patty home that first summer, and told us we’d have milk and butter for ourselves and money from selling the rest of it to the neighbors, Alma and I said we were big enough to help. We planned which houses we’d go to and which we’d skip and we never meant to stop at the Garneys’, but that first week, walking home with the near-empty pail swinging between us, we saw Jessie crouched under her porch, skinny arms wrapped around her bent knees, and I couldn’t help going over to her and touching her shoulder. Her head came up, eyes shining like I thought emeralds would, the bruise under the left one coal-dark.

“What happened?” I asked, and Jessie shook her head. Alma reached out, but stopped, her fingers not quite touching Jessie’s face, milk-white under the freckles and the bruise.

“Doesn’t matter.” And the hopelessness in her voice was echoed in the thin, mewling cries coming from the house, and in the tired voice that called out, “Who’s out there, Jessie? Who’re you talking to?”

“It’s Alma and Marie, Ma,” she answered. I wondered if Jessie had been watching us since we first came down our steps that day, and how many other mornings she left her house to crouch on cold dirt and watch who went past.

We heard steps on the porch, and we moved away from Jessie to where her mother could see us. “Good morning, ma’am,” I said. “My sister and I are selling milk from our cow. We could come by tomorrow if you’d like, a penny a cup.”

She stared at us, her eyes flat and dull as the stones kicked around in the middle of a road, fussing baby in her arms, another, just old enough to walk, clinging silently to her skirts. She pursed her lips, then nodded slightly. “That’d be all right. Tomorrow. Two cups, I think.” She bent over the rail. “You come in now, girl, take the baby.” Jessie stood up and went inside. We’d turned around by the time we heard the door slam shut.

Jessie didn’t come to school that day or the rest of the week. It was different for boys. Her brothers came no matter how many bruises they wore on their faces. The teacher never asked about it, of them or any other child, not like nowadays when such things could not go unremarked or unreported. Why would the teachers care when they had rulers and switches always close to hand and used them every day on one or another of their students? Not me or Alma, though. Never on us. We never talked out of turn, and our work was always done well. We knew what school meant for us. It was the way out. Out of icy mornings in the shed, when we took turns milking. Out of a home where there wasn’t enough to eat and we’d always pretend we were full anyway because the pain on our mother’s face when we’d asked for more, before we understood how much had changed, was so much worse than the hurt in our bellies. Alma and I made plans. We’d be teachers ourselves, or clerks in a store, any work would be fine as long as it was in a place that was warm and clean and dry, and we could use our minds more than our bodies. Bodies wore out or broke. Like our father’s under the wheels of a wagon, from one instant to the next. Like our mother’s in Johnson’s laundry, worn down day after day from lifting the water-logged clothes from one vat to the next, her hands and arms scoured by hot water and cheap soap made from tallow and ash.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 137, No. 3 & 4. Whole No. 835 & 836, March/April 2011»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 137, No. 3 & 4. Whole No. 835 & 836, March/April 2011» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 137, No. 3 & 4. Whole No. 835 & 836, March/April 2011» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.