“Tell me about it,” Carmody said.

“Ackerman and I had a talk after you left. He wants you to keep working on your brother. You said you could make him listen to reason. Does that still go?”

“Sure I can,” Carmody said. The tension dissolved in him and he let out his breath slowly. With time he could work something out. “I’ll need a few days,” he said.

“Two days is the limit. That’s Ackerman’s final word.”

“Okay, two days then,” Carmody said. He was trembling with relief; Eddie wouldn’t die tonight. “I can handle it in two days, I think.”

“Good. And if you want to pound somebody, well, pound some sense into your brother.”

“I’m sorry about tonight, Dan,” Carmody said slowly.

“Don’t worry about that. Let me know when you’ve made progress.”

“Okay, Dan.”

Carmody put the phone down and saw that his hands were trembling. Relief did that to you, just like fear. Eddie was safe for two days. Would it narrow down to hours? And then minutes?

Carmody turned on the record player and walked deliberately to the liquor cabinet. He took out a fresh bottle and put it on the table beside his chair. What had he told Nancy? That he didn’t drink because he didn’t want to be anyone else. Did that still hold? He sat down slowly, heavily, and let his big hands fall limply on either side of the chair. Not any more. I’d love to be someone else right now, he thought.

Carmody reached for the bottle the way a desperate man would turn on the gas...

He was awakened by a sound that seemed to be pounding at the inside of his head. Pushing himself to a sitting position, he stared blankly around the dark room. He checked his watch; the illuminated hands stood at one-forty-five. He had been out for hours. His coat lay beside him on the floor and his collar was open. There was a dull pain stretching across his forehead, and his stomach was cold and hollow.

The knocking sounded again, more insistently this time. Carmody snapped on a lamp, pushed the hair back from his forehead and went to the door.

Nancy stood in the corridor, swaying slightly; the night elevator man held her arms to keep her from falling. “She insisted I bring her up, Mr. Carmody,” the man said. “I rang you but didn’t get no answer.”

“It’s alright,” Carmody said. “Come in, Nancy. What’s the matter?”

She swayed toward him and he caught her shoulders. “Take it easy,” he said.

“Beaumonte kicked me out,” she said, grinning brightly at him; the smile was all wrong, it was as meaningless as an idiot’s. “Got a drink for a cast-off basket case?”

“We can find one.” Carmody led her to the sofa, put a pillow behind her head and stretched out her legs. Turning on the lights, he made a drink and pulled a footstool over beside the couch.

“Take this,” he said. She looked ghastly in the overhead light; her face was like a crushed flower, lipstick smeared, make-up streaked with tears. “What happened?”

“He kicked me out, Mike. He gave me to some friends of his first. People he owed a favor to. Or maybe I’m flattering myself. Maybe they’re people he doesn’t like. They took me to a private house near Shoreline.” She shook her head quickly. “They were real gents, Mike. They gave me cab fare home.”

Carmody squeezed her hand tightly. “Take the drink,” he said.

“I don’t know why I came here. I shouldn’t have. I guess it was seeing you in the fight. You’re the only thing they’re afraid of.”

“Did you hear any talk about me after I left? From Ackerman, I mean? About me or my brother?”

She stared at him, her mouth opening, and then she shook her head from side to side. “Oh God, oh God,” she whispered. “You don’t know?”

“What?” Carmody said, as the shock that anticipates fear went through him coldly.

Clinging to his hands, she began to weep hysterically. “It’s all over town. I heard it from Fanzo’s men, and on the radio in the cab. Your brother was shot and killed a couple of hours ago.”

She was crying so hard that it took Carmody several minutes to get any details. When he learned where it had happened he stood up, his breathing loud and harsh in the silence. “You stay here,” he said in a soft, thick voice. He picked up his coat and left the room.

The shooting had occurred a block from Karen’s hotel. Carmody got there in twenty minutes by pushing his car at seventy through the quiet streets. The scene was one he knew by heart; squad cars with red beacon lights swinging in the darkness, groups of excited people on the sidewalks whispering to each other and women and children peering out from lighted windows on either side of the street. He parked and walked toward the place his brother had died, a cold frozen expression on his face. A cop in the police line recognized him and stepped quickly out of his way, giving him a small jerky salute.

Lieutenant Wilson was standing in a group of lab men and detectives from Klipperman’s shift. One of them saw Carmody coming and tapped his arm. Wilson turned, his tough, belligerent features shadowed by the flashing red lights. He said quietly, “We’ve been trying to get you for a couple of hours, Mike. I’m sorry about this, sorry as hell.”

Carmody stopped and nodded slowly. “Where’s Eddie?” he said.

“They’ve taken him away.”

“He’s dead then,” Carmody said. Nothing showed on his face. “I was hoping I’d got a bum tip. What happened?”

“He was shot twice in the back. Right here.”

Carmody stared at the sidewalk beyond the group of detectives and saw bloodstains shining blackly in the uncertain light. In the back, he thought.

“We’ll break this one fast, don’t worry,” Wilson said. “We’ve got a witness who saw the shooting. She was a friend of Eddie’s. Karen Stephanson. You know her?”

“She saw it, heh? Where is she now?”

“At Headquarters, looking at pictures.”

Carmody turned and walked away, his heels making a sharp, ringing sound. Wilson called after him but Carmody kept going, shouldering people aside as he headed for his car.

It took him twenty minutes to get back to center-city. He parked at Oak and Sixteenth, a few doors from the morgue, and walked into the rubber-tiled foyer. The elderly cop on duty got to his feet, a solemn, awkward expression on his face. “He’s down the hall. In B,” he said. “You know the way, I guess, Sarge.”

Carmody pushed through swinging doors and turned into the second room off the wide, brick-walled corridor. Three men were present, a pathologist from Memorial Hospital, a uniformed cop and an attendant in blue denim overalls. The square clean room was powerfully illuminated by overhead lights and water trickled in a trough around the edge of the concrete floor. The air smelled suspiciously clean, as if soap and brushes had been used with tireless efficiency to smother something else in the room.

Eddie lay on a metal table with a sheet covering the lower half of his body. The brilliant white light struck his bare chest and glinted sharply on the smears and streaks of blood. His shirt, which had been cut away from him, lay beside the table on the floor.

Carmody stared at his brother’s body for a few moments, his features cold and expressionless. A lock of hair was curled down on Eddie’s ivory-pale forehead and his face was white and empty and still. The choirboy who stole the show at St. Pat’s, Carmody thought. Who wanted to play it straight, get married and have kids. That was all over, as dead as any other dream. One of the men said something to him hesitantly and awkwardly. “Damn shame, sorry...” Carmody couldn’t speak; a pain was pressing against his throat like a knife blade. He nodded slowly, avoiding their eyes.

Читать дальше

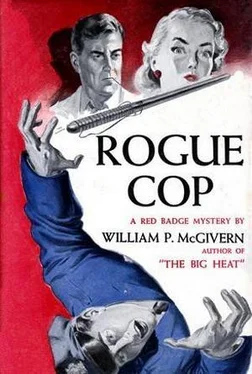

![Уильям Макгиверн - Завтра опять неизвестность [английский и русский параллельные тексты]](/books/35168/uilyam-makgivern-zavtra-opyat-neizvestnost-angli-thumb.webp)