“Was there a wallet in the car?”

“No. Nothing. No film, either.”

“Film?”

“She was editing film out there on Rancher Road. So the film is gone and her handbag’s gone, and her keys are gone, so I have to assume the killer took all those things, am I right?”

“Well, yes, that sounds reasonable.”

“So why doesn’t it sound reasonable to Haggerty?”

“Haggerty?”

“The man who’s handling the state’s case.”

“I’m not following you, Matthew.”

“I mean, he’s got to assume the same thing I’m assuming, doesn’t he? That the killer took those things?”

“Yes?”

“But he thinks my client is the goddamn killer! So what happened to all that stuff my client had to have taken if he is , in fact, the killer? Where is it? If Haggerty had it, he’d have listed it on his response. So he hasn’t got it. So where is it? And where’s the shovel or the spade or whatever the hell my client allegedly used to bury his clothes in the backyard? I have to assume he hasn’t got that, either.”

“So? Can’t he make a case without—”

“Oh, he’s sure as hell going to try. But why isn’t it bothering him?”

“Should it be bothering him?”

“It’s bothering me . Because it makes me wonder what he’s got , Susan. Never mind what he hasn’t got. What has he got ? What has he got that makes him feel so confident he can send Markham to the electric chair? He hasn’t got the missing handbag, the missing keys, the missing film, the missing shovel. The killer’s got those, Susan. But Haggerty doesn’t seem to give a damn. He’s got two witnesses and he’s got some bloody clothing and a bloody knife, and he seems content to be going with that alone. Why?”

“Why don’t you ask him what else he’s got?”

“He’s already told me what he’s got. My demand for discovery specifically listed tangible papers or objects.”

“Well — is he allowed to hide anything?”

“No, he can’t do that.”

“He’s required to tell you—”

“Yes. Required by law. He doesn’t have to tell me how he plans to try his case, of course, but—”

“But he does have to tell you what evidence he has.”

“Yes.”

“Well, has he told you?”

“I have to assume so.”

They were silent for several moments. The sun was all but gone.

She said, very softly, “I wish I could help you, Matthew.”

“I’m sorry to bother you with this crap,” he said.

They fell silent again.

“What else is bothering you?” she asked.

He sighed deeply.

“Tell me.”

“I may be in over my head, Susan. I may be sending an innocent man to the chair because I don’t know what the hell I’m doing.”

“You do know what you’re doing,” she said.

“Maybe.”

“Is he innocent?”

“I have to believe that.”

“But do you?”

“Yes.”

“Then you won’t let them kill him, Matthew,” she said, and took his hand.

In bed with her, the case was still with him.

The reflected light from the pool outside flickered on the ceiling. In his mind, there was the same elusive wavering of light, slivers of evidence fitfully moving at the whim of the wind. Her long hair fell over his face, her mouth covered his. His eyes were closed, the splintered light danced behind them. She lowered herself onto him.

And for just a little while, he forgot the handbag, forgot the keys and the film, forgot the shovel, forgot all the missing things, and there was only the here and the now, and the remembered heat of this woman he once loved and perhaps now loved anew.

And then he thought again, The killer has those things.

The sign on the wooden post read:

Orchidaceous

Exotic Orchids

There was an address lower on the post: 3755. A dirt road to the left of the post ran off Timucuan Point Road through thick clusters of cabbage palm and palmetto. The place used to be a cattle ranch, and the entire property — a thousand acres of it — was still fenced with barbed wire.

The dirt road ran past a lake shrouded by oaks.

There were alligators in the lake.

The dirt road continued along the side of the lake for half a mile, where it ended at the main house. The greenhouses were set back two hundred yards from the main house, across from what used to be the stables when there were still horses here. Situated catty-wampus to the greenhouses was a windowless, unpainted cinder-block structure that housed the generator. The building was perhaps fifteen feet wide by twenty feet long. It had a dirt floor. It had a louvered ventilating slit high up on one of the walls. A naked lightbulb hung in the center of the space, operated from a switch just inside the thick wooden door. There was a padlock on the door.

He unlocked the door and snapped on the light.

She was wearing only high-heeled red leather boots. Soft red leather. The kind of boots that looked rumpled at the ankles. Tall boots that folded over onto her thighs. She had long red hair a shade darker than the boots. A tuft of even darker red hair curled in a wild tangle at the joining of her legs. She sat in the dirt in one corner of the room, behind the generator, her hands tied behind her, her legs bound at the ankles. A three-inch-wide strip of adhesive tape covered her mouth. Her eyes flashed green in the dim glow of the hanging lightbulb.

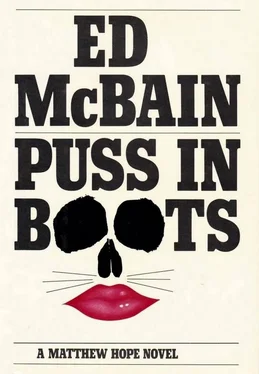

“Evening, Puss,” he said.

He closed the door behind him, and set down the shopping bag he’d been carrying.

“Miss me?” he asked.

He came toward her, walking around the generator, and she cowered away from him, trying to move deeper into the corner. He looked down at her. He shook his head, clucked his tongue.

“Look at how filthy you’ve got,” he said, “sitting here naked in the dirt. Shame on you. Woman who always took such good care of herself.”

He kept looking down at her.

“Maybe I ought to take that tape off your mouth,” he said. “You’re not gonna scream if I take it off, are you? Not that anybody’d hear you. You promise you won’t scream if I take off the tape?”

She nodded.

“You’re sure now? You won’t scream like you done last time?”

Another nod, green eyes wide.

“Well, then, let’s just take off the tape,” he said, and crouched beside her. He smiled, twisted her head, found the end of the tape, and with one violent tug ripped it free. She bit her lip, stifling a scream.

“Hurts, don’t it, when I pull the tape off that way?” he said.

She was still biting her lip.

“You hear what I said? Hurts, don’t it?”

“Yes,” she said.

He nodded, got to his feet again, and went back to the door where he’d left the bag.

“You hungry?” he asked.

“Yes,” she said.

He carried the bag back to where she sat in the corner.

“Bet you’re hoping there’s a sandwich in here, ain’t you?” he said.

“Yes,” she said.

“Bet you’d eat scraps I spit on, wouldn’t you?” he said.

She did not answer.

“I asked you a question,” he said.

“I’m not that hungry,” she said.

“Don’t get sassy,” he said.

“I’m sorry, I—”

“Did you hear me ask you a question?”

“Yes, and I’m... I’m sorry I was... if I sounded sassy.”

“Or maybe you don’t want me to feed you, is that it?”

“No, I want you to.”

“Want me to what?”

“Feed me.”

“Even scraps I spit on?”

“No, I... I don’t want to eat anything like that.”

“You getting sassy again?”

Читать дальше