“I don’t think he did it, Morrie.”

“I’m sure he did,” Bloom said, and sighed again.

Matthew was just leaving his office that Monday afternoon when the telephone rang. He muttered “Shit,” put down his briefcase on the table inside the door, crossed to his desk, lifted the telephone receiver, and said, “Hello?”

“Matthew, hi. Its Susan.”

His private line. His former wife.

“I hear you’ve taken on a big one,” she said.

“Who told you?”

“Eliot McLaughlin.”

The attorney who had handled the settlement agreement for her. The man responsible for siphoning off a goodly amount of Matthew’s income each and every month of the year. Matthew bore him no ill will. He merely wished he would get hit by a bus.

“When can I see you?” she said.

Last spring, while Matthew was “sticking his nose into a narcotics case” — as Bloom had so delicately put it — he and Susan, for reasons still not clear to either of them, had begun seeing each other again. “Seeing” was a euphemism. They had, in fact, begun sharing each other’s company in a manner a good deal more intimate and passionate than when they’d been man and wife. Go figure it. He hadn’t seen her since Thanksgiving Day, when together they’d placed a long-distance call to their daughter Joanna at her boarding school in Massachusetts. The Simms Academy. It sounded like a military school for recalcitrant girls. Actually, it was quite good, and Joanna — after more than two months of bitter complaining — seemed genuinely beginning to enjoy it. This may have had something to do with the fact that she’d met a seventeen-year-old quarterback named Thomas Darrow, and they had become what Joanna called “a thing.” Joanna was fourteen years old. Matthew could only hope “a thing” wasn’t another euphemism.

He and Susan had become “a thing,” too.

In provincial, gossipy Calusa, there were not many people who didn’t know that Matthew and Susan were seeing each other again. Some people cynically maintained that Matthew’s fresh desire had less to do with Susan’s obvious charms than with an urgent need to get rid of his onerous alimony burden. Other people genuinely wished that the sound of wedding bells would be heard again in the not too distant future. Still others gave the new (or old, or both) lovers two, three months at the most. But Matthew had been seeing Susan for six months now, and when he heard her say, somewhat breathlessly, “When can I see you?” there was an odd little stirring in his groin that he could not attribute to indigestion.

“Tonight?” he said.

“We have a lot to talk about,” she said.

“What time?” he asked.

“What time do you get out of there?”

“I was just leaving the office. I’m running out to Sunrise Shores to interview a witness.”

“What time do you think you’ll be finished?”

Matthew looked at his watch.

“Four o’clock?” he said.

“Come directly here,” Susan said. “Do not pass Go, do not collect two hundred dollars.”

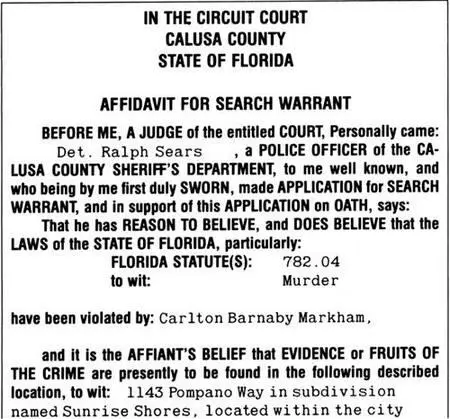

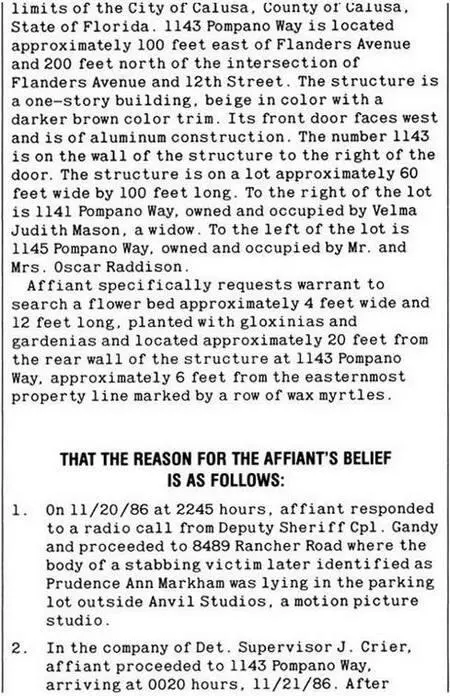

Oscar Raddison was a man in his late fifties, his blue tank top bulging with the muscles of a weight lifter, his red running shorts revealing thighs like oaks, his body resplendently tanned, his brown eyes sharp and intelligent. He admitted Matthew to the house, showed no reluctance at all to having their conversation taped or to later giving the same information in a deposition. He even offered Matthew a drink. This was at two-thirty in the afternoon. Matthew declined, and Raddison went to the refrigerator to get himself a Heineken.

He popped the can, and then said, “I’d like to be finished here before Lou gets home. Louise. My wife. We’re going out to an early dinner.”

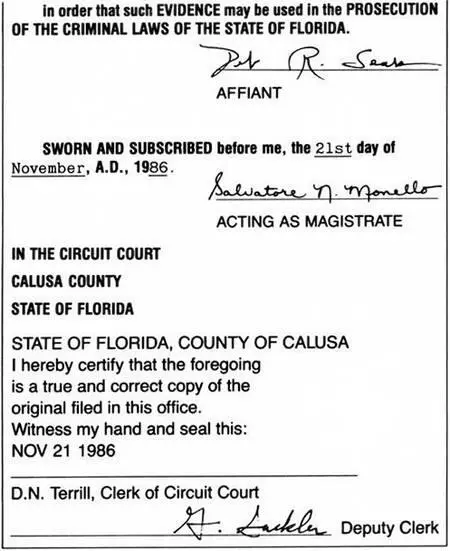

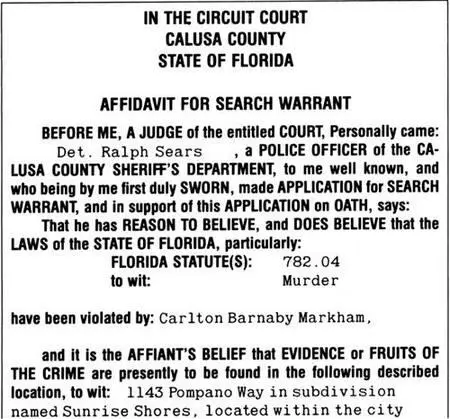

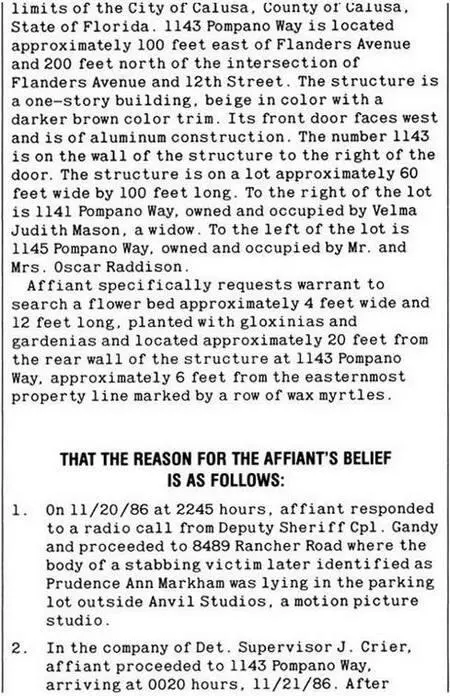

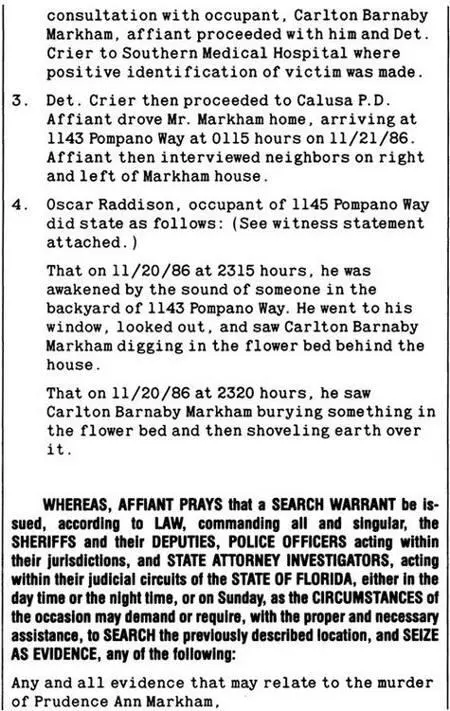

“I won’t take much of your time,” Matthew said, and started the recorder. “Mr. Raddison, according to the witness statement you gave Detective Sears of the Sheriff’s Department—”

“Nice feller,” Raddison said.

“I haven’t met him yet,” Matthew said.

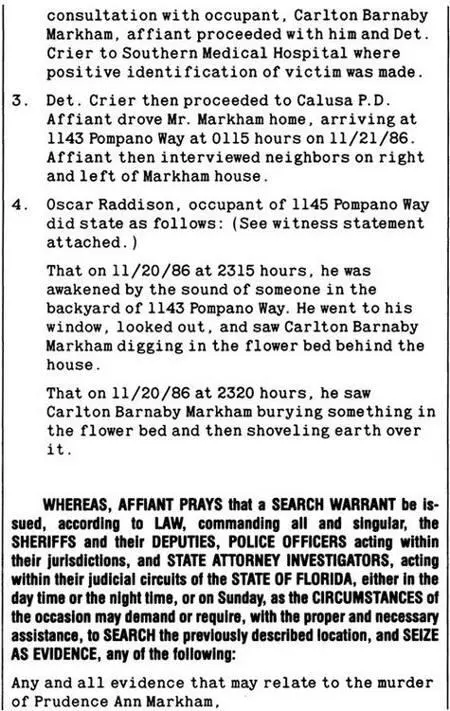

“Smart, too,” Raddison said. “When I told him about that flower bed, he knew right off he’d find incriminating evidence there.”

“You told him this when he came back to the house on the night of the murder, isn’t that correct? Well, it would have been morning by then, about a quarter past one in the morning.”

“Yes.”

“About the same time Detective Bloom was talking to Mrs. Mason.”

“I wouldn’t know about that.”

“Well, her witness statement was taken at twenty after one that morning.”

“I still wouldn’t know anything about it. Did she see him, too? Out there in the garden?”

“What did you see?” Matthew asked.

“Carlton. With a spade in his hands. Digging up the garden.”

“What time was this?”

“I woke up around a quarter past eleven—”

“Was it the sound of the digging that woke you up?”

“No. I had to pee. I wake up two, three times a night to pee. A side effect.”

“Of what?”

“I’ve got a high cholesterol problem, the doctor put me on medication. One of the side effects is excessive urination. I usually go to bed around nine, wake up around eleven, eleven-thirty, then again at two, then again at five, then sleep in till eight, when I get up and go over to Nautilus. Flatulence is another side effect.”

“I see,” Matthew said.

“I guess I shouldn’t be saying all this with that machine going, but it’s the truth.”

“So you woke up to go to the bathroom at eleven-fifteen—”

“Right. And that’s when I heard someone digging in the yard next door.”

“Someone. Not Mr. Markham.”

“Well, I didn’t know it was Carlton till I took a look.”

“When was that?”

“After I finished peeing.”

“Looked from where?”

“The bathroom window.”

“Was the light on in the bathroom?”

“No, I never turn it on, it’d wake Lou. I just find my way there in the dark — I’ve got this little night light in the hall, I never have a problem.”

“So the bathroom was dark.”

“Yes.”

“And you looked from the bathroom window over to the Markham backyard, is that right?”

“That’s what I did.”

“Where is the bathroom, Mr. Raddison?”

“Just down the hall from the bedroom.”

“At which end of the house?”

“Right there,” Raddison said, and pointed.

“That would be the southern end of your house, wouldn’t it? The end farthest from the Markham house.”

“The southern end, right. But it’s not all that far. And I’ve got good eyesight, check with my doctor if you like. Never wore glasses in my life, still don’t. I saw Carlton plain as day. Digging there in the flower bed.”

“With what?”

“Well, with a spade. Or a shovel. Either one, I couldn’t tell you which.”

“He had a shovel, or a spade, in his hands.”

“Yessir.”

“And was doing what with it?”

“Digging a hole in the flower bed.”

“How large a hole?”

“Big enough to hold them clothes and the knife, I reckon.”

Читать дальше