“You filthy rotten scum,” the doctor said in a soft but savagely bitter voice. “You’re nothing but dirt — you don’t have an ounce of decency in your miserable body. You’re tough, sure — blood pressure normal four hours after being shot. It’s the reaction you find in animals. Your guts come from that gun in your hand. Without it you’re just something crawling through the mud.”

“Shut up!” Earl yelled at him. “You say anything else and I’m going to put a hole right through your head. You think I’m kidding?”

He forced himself to his feet, swaying like a badly hurt fighter; a terrible weakness was suddenly spreading through his body. “You think I’m kidding, eh? You want to die in front of that little girl?”

“No — I believe you.” The doctor’s lips were stiff and dry. He took a step away from Earl, holding his daughter tightly in his arms. “Just relax. You’re sick.”

Ingram stepped quickly in front of the doctor. “You want to shoot somebody, white boy, you shoot me,” he said in a soft, trembling voice. “Go ahead. You’re the big hero with all the medals. Here’s a chance to get another. Shoot me, and then shoot the doc who saved your life, and then the little girl. You’ll get a big medal. But you’ll be all alone then, white boy. Remember that.”

“Get out of the way,” Earl said. “Get out of the way.”

“I’m taking these people home. I promised them that. Start backing toward the door, Doc. If he shoots anybody, it’s going to be me.”

“Sambo!” Earl cried frantically. “Who are you with?”

“I’m taking them home. That comes first.”

“Well, goddam,” Earl said, swaying weakly. “I should have expected this.” The gun swung loosely to his side, the muzzle pointing at the floor. “You’re ratting out.” The words sounded thick and feeble in his ears. He sat down on the sofa, his body moving with sluggish caution, and his muscles and nerves cringing at the sick feeling fanning through his body. “All right, take ’em home,” he said, breathing heavily. “Take ’em home, hear? Take everybody home. Everybody with a home should go home.”

Ingram crossed the floor swiftly and took the gun from his limp hand. “I’ll come back,” he said, touching Earl’s shoulder. “Don’t worry.” He wet his lips, trying to think of something else to say; all his anger had gone. “I’m coming back,” he said. “You get some rest.”

Earl lay back on the couch, breathing through his open mouth. He stared at Ingram with sick, glazed eyes, and nodded weakly. “I’ll wait for you, Sambo. Nothing else I can do.”

At three o’clock in the morning the village of Crossroads lay sleeping in faint moonlight, its streets shining emptily and bursts of wind tugging with a lonely sound at the canvas awnings above the dark shops.

The all-night drugstore and the gas station at the bend of the federal highway were exceptions to the black silence; they were courageously open for business as usual, bright and defiant flags against the night.

At police headquarters in the Municipal Building, Kelly was sitting opposite the sheriff’s desk, a cigarette burning in the ash tray near his elbow, and a sheaf of notes and reports in his hand. Morgan had gone off duty, and the sheriff and several of Kelly’s men were working with the troopers at the roadblocks surrounding Crossroads.

Kelly swiveled in his chair and stared at the county map on the wall, focusing his eyes on the black circle the sheriff had drawn around the area southwest of Crossroads. It was a pretty big noose, he thought. Too big. The men were trapped all right; roadblocks sealed off the section efficiently. But they had a vast territory to move around in, and someone might be hurt, before the noose was jerked tight around their necks. They had to get them fast. That was the essential thing at this end of the job.

Washington was working on the other side of it. They had identified the slain holdup man. Burke, an ex-cop from Detroit, bounced for using his badge as the emblem of a private collection agency. It was all over for him now, Kelly thought. He’d tried for the big time and missed by a country mile. Washington was running down a man named Novak, who had been an associate of Burke’s in the past few months. Maybe Novak wasn’t part of the bank job. But they wanted to make sure. Dozens of agents were after him, along with the police departments of every state. Novak, whoever he was, didn’t have a prayer.

That left the man inside the noose. John Ingram, a Negro. The police in Philly had run a cautious check on him. He hadn’t been in trouble before. He was known as a quiet, good-humored fellow, a dealer in a gambling joint, one of four brothers with good records and responsible jobs. Ingram puzzled Kelly; he just didn’t fit the picture. Bank robbers fell into categories. They were usually impulsive and reckless men, indifferent to risk or danger. Hard to stop, since banks seemed to challenge their outlaw temperaments, but very easy to apprehend; they inevitably spent their stolen money foolishly, drinking and brawling, and showing off until they brought the law down on themselves.

The white man, yes. They didn’t have his name yet. Just the sheriff’s description: big and rangy, with steady, sullen eyes. He fitted. Moody, restless, a man with a grudge.

The door opened and Kelly turned from the map, expecting Sheriff Burns; but it was his daughter, Nancy, bundled up in a hooded raincoat and carrying a large thermos in her arms. She said “Hello,” rather awkwardly, and put the thermos on the counter. “I thought Dad would be here.”

“He’s out at one of the roadblocks.” Kelly glanced at his watch. “Should be back pretty soon.”

“Would you like coffee?” She put her raincoat over a chair and ran a hand nervously over her long blond hair, “I couldn’t sleep — I wondered if you and Dad might like something hot to drink.”

“That sounds fine,” Kelly said. He leaned against the desk and watched her pour steaming coffee into the metal cups she unscrewed from the top of the thermos. There was an efficient haste in all her movements as if she were eager to get the job over and done with; he found it difficult to imagine her doing anything at a casual, leisurely pace. Rush, rush, he thought. He was puzzled by this girl; there were contradictions about her that he couldn’t understand. She seemed warm and cold, wistful and hard, pensive and indifferent — but all the same time, the emotions blended together in aggravating and illogical patterns. He had been thinking about her quite a lot since dinner — not simply because she was a young and attractive female, but because the incongruities in her manner aroused his professional interest in puzzles.

They sat for a moment in silence, Kelly perched on the desk, the girl studying the splinter of light moving on the glossy black tip of her pump. The office was warm and quiet, a comfortable coffee-fragrant refuge against the night pressing against the frosted windows. But the silence between them wasn’t comfortable, Kelly realized; she seemed awkward and strained for some reason.

He couldn’t imagine why. She was good-looking enough, he thought, studying her smooth profile. Just a little bit stiff and shy, but everything else was definitely all right; nice blond hair, fresh clean skin, intelligent eyes and mouth. No discernible flaws. She was wearing a soft beige sweater with a neatly pegged tweed skirt, and the full curving lines of her bosom and hips were very evident as she twisted slightly in the chair and crossed her smooth, slim legs.

So why wasn’t she married? he thought.

“You say you had trouble sleeping tonight?” he asked her politely.

Читать дальше

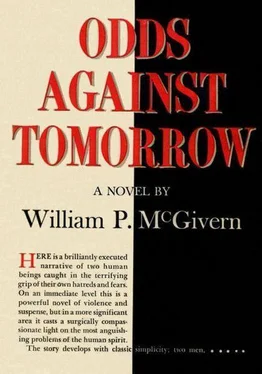

![Уильям Макгиверн - Завтра опять неизвестность [английский и русский параллельные тексты]](/books/35168/uilyam-makgivern-zavtra-opyat-neizvestnost-angli-thumb.webp)