Novak shook his head. “I don’t want that stuff, Johnny. I’m no pawnbroker.”

“Will you take my note then? Will you, Mr. Novak?”

“That depends. First of all, let’s start leveling with each other, okay?” Novak stood and began to make himself a drink at the dresser, and Ingram twisted on the chair to watch him with wide, frightened eyes. “What do you mean, Mr. Novak?” he said, in a soft, husky voice. “I’m telling you the truth, I swear it.”

“Save it, save it,” Novak said irritably. He sat down again and stared at Ingram in a heavy silence. “You’re in trouble,” he said at last. “So let’s cut out the crap.”

“I swear to God—”

“You’re in trouble with Tenzell,” Novak said, his voice falling coldly across Ingram’s feeble protest. “You gave an undated IOU to Billy Turk for six thousand dollars. And he sold it to Tenzell at a twenty-five per-cent discount. Now Tenzell wants the money, doesn’t he? Now — tonight.”

Ingram wet his lips. “Who told you, Mr. Novak? Is it all over town?”

“Never mind who told me. It’s true, isn’t it?”

“Yeah, it’s true,” Ingram said, shaking his head wearily. “I shouldn’t have tried to con you. I’m in bad trouble, Mr. Novak. If I don’t get that dough, I don’t know what’s going to happen to me.”

Novak smiled faintly. “I can tell you, Johnny. You’ll get the hell beat out of you by some of Tenzell’s boys. Not just once or twice, either. That’s the best that can happen, I guess you know. If Tenzell gets really mad, you’re through. Kaput.”

Now that the charade was over, Ingram felt a bone-deep lassitude settling over him. “Can you help me out, Mr. Novak? I’ll pay you back. You know that.”

Novak stood and walked slowly over to the windows, holding the cigar in his teeth, and rolling the glass between his big hands. “Maybe,” he said. “But it’s a lot of cash.”

“I know — I’ll give you any kind of a deal you want.”

Novak frowned out the window at the bright sunlight that was glinting on the sides of the city’s buildings and falling in long patterns into the streets. In the blue sky a four-engined plane gleamed like a tiny silver cross. “This is going to be operation backscratch,” he said, turning and looking at Ingram. “Understand? I’ll lend you the dough. But I need some help from you. That sound all right?”

“Why, sure,” Ingram said, smiling anxiously. “I’m grateful to you, Mr. Novak. I’ll do anything if you just pull me out of this hole. You know that.”

“Okay,” Novak said, returning to sit on the edge of the bed. “I’m planning a job, Johnny. A bank job. And I need a colored guy to make it work. A colored guy is the shoehorn that gets us into the bank. That’s you, Johnny. A nice shiny shoehorn.”

Ingram was trying to smile, but it was a shaky effort; he felt empty and weightless, his insides consumed by fear. “You’re kidding, Mr. Novak. You’re kidding me.”

Novak’s eyes were cold. “I don’t kid around, Johnny. Neither does Tenzell. Think it over.”

“But I’ve never done anything like that, Mr. Novak. I... I don’t have the guts for it.”

“Guts you don’t need. I’ve got other guys for that end of the job. It’s your skin I’m buying, nothing else.”

“Mr. Novak, you’re making a mistake.” Ingram shook his head desperately. “I’m a card player, just a plain ordinary citizen. You don’t want me on a job like this.”

“Is that your answer?”

“Wait, please wait! I’m scared — I’m scared, Mr. Novak.”

“Of Tenzell? Of me?”

“Let me just think a minute. Please, Mr. Novak.”

“Sure, take your time. It’s a big, solid job, if you’re interested in details. And you’ll get a quarter of the take. Think it over. It’s better than winding up in an alley looking like somebody stuck your head in a mix-master.”

Ingram smiled nervously and lighted a cigarette, sucking the smoke deeply into his lungs. “Yeah, sure,” he said. If his mother were alive it would be different, he thought despairingly; not easier, but different. For a long while taking care of her was all that mattered. He had made all his decisions with her in mind; keeping her comfortable, playing cards with her, seeing that there was plenty of food in the house and all the bills paid — those were his first considerations. He wanted her to be comfortable and quiet in her last years, free to entertain her old friends, to go to church and live the kind of respectable life she enjoyed so much. The Tenzell business would be different if she were alive. He wouldn’t let that hurt her, even if it meant stealing the money. If she were living now, he’d grab Novak’s offer without a second thought. One thought would be enough — her comfort and peace. But now there was just himself, and it was easier to be afraid. But why should he be? What am I scared of? The questions scurried like rats through his mind. He could get away from Tenzell, blow out of town. But they’d catch him some day. It wouldn’t be a bullet, that’s what made him sick with terror. They’d come into his room on a dark night or catch him in an alley, and there was no telling what they’d do to him — enjoying it, laughing at him. He had a terror of being beaten; it was an old fear; it had been with him all his life.

The door opened and Burke came in carrying the morning papers under his arm. He looked questioningly at Novak, and Novak said, “Well, how about it, Johnny? Time’s a-wasting. You want me to take Tenzell off your back?”

Ingram tried to smile but the effort only stretched the skin tightly over his sharp cheekbones. “I’m your shoehorn, Mr. Novak.”

“What’s that?” Burke said, laughing; his face was flushed and his eyes bright with a stupid good humor. “What’s the shoehorn bit, Johnny?”

Novak glanced irritably at him. “It means Johnny’s in. That’s the deal, four of us. Now we get down to work.”

“Well, let’s have a drink and celebrate,” Burke said. “What’s yours, Johnny?”

“Make ’em light,” Novak said. “We’ve got work to do.”

“Sure, sure,” Burke said in a big, genial voice. As he turned toward the dresser the phone rang, and Novak lifted the receiver and said, “Yeah? Oh, sure. Come on up, Tex. We’re ready to roll.”

“Tex?” Ingram raised his eyebrows and smiled faintly. “Sounds like I’m moving in high society.”

“He’s okay,” Novak said. “Don’t worry.”

Earl’s mood was one of relaxed and uncomplicated contentment as he stepped into the elevator; the pressure within him seemed to have been dissipated by his decision to accept Novak’s offer. Now he was sustained by a solid and unfamiliar sense of importance; he knew he was on the inside of something big and that put a lift in his stride. You made your breaks, he thought, as the elevator began to rise.

He wasn’t worried about failure, because he didn’t have the imagination to picture disaster in vivid and personal terms; it was this lack that made him a good soldier. The whole thing might go wrong, of course; there was always that chance. That much he understood; but he couldn’t conjure up the colors and textures and details of failure — sirens, for instance, or the smash of bullets into his body or the potential horror of waiting to die in a gas chamber or electric chair.

He didn’t think of these things. Unconsciously he had shifted the responsibility for what he was about to do onto Novak’s shoulders. Novak was running things. It was a little like the Army, he thought comfortably; you did what you were told, even if the orders were stupid and dangerous. That didn’t matter; if things went wrong it wasn’t your fault.

Читать дальше

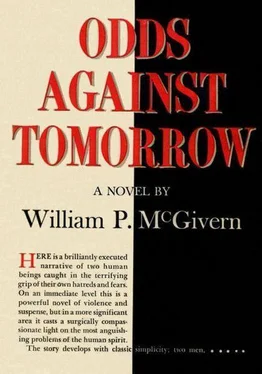

![Уильям Макгиверн - Завтра опять неизвестность [английский и русский параллельные тексты]](/books/35168/uilyam-makgivern-zavtra-opyat-neizvestnost-angli-thumb.webp)