The humans did play through the eleventh hole, pretty happy with their scores to date. Then they teed off on the twelfth hole, the lake hole, which was the fairway on which Ginger McConnell was killed. Not wishing to jinx themselves, no one spoke of it except the cats.

As luck would have it, Marshall hit into the woods. He blamed the bad shot on his sore hands, which Harry noticed were bandaged. Both Nelson and Susan stayed on the fairway, but Susan had a difficult shot up to the green, thanks to the angle at which she found her ball. Such challenges revved Susan’s motor.

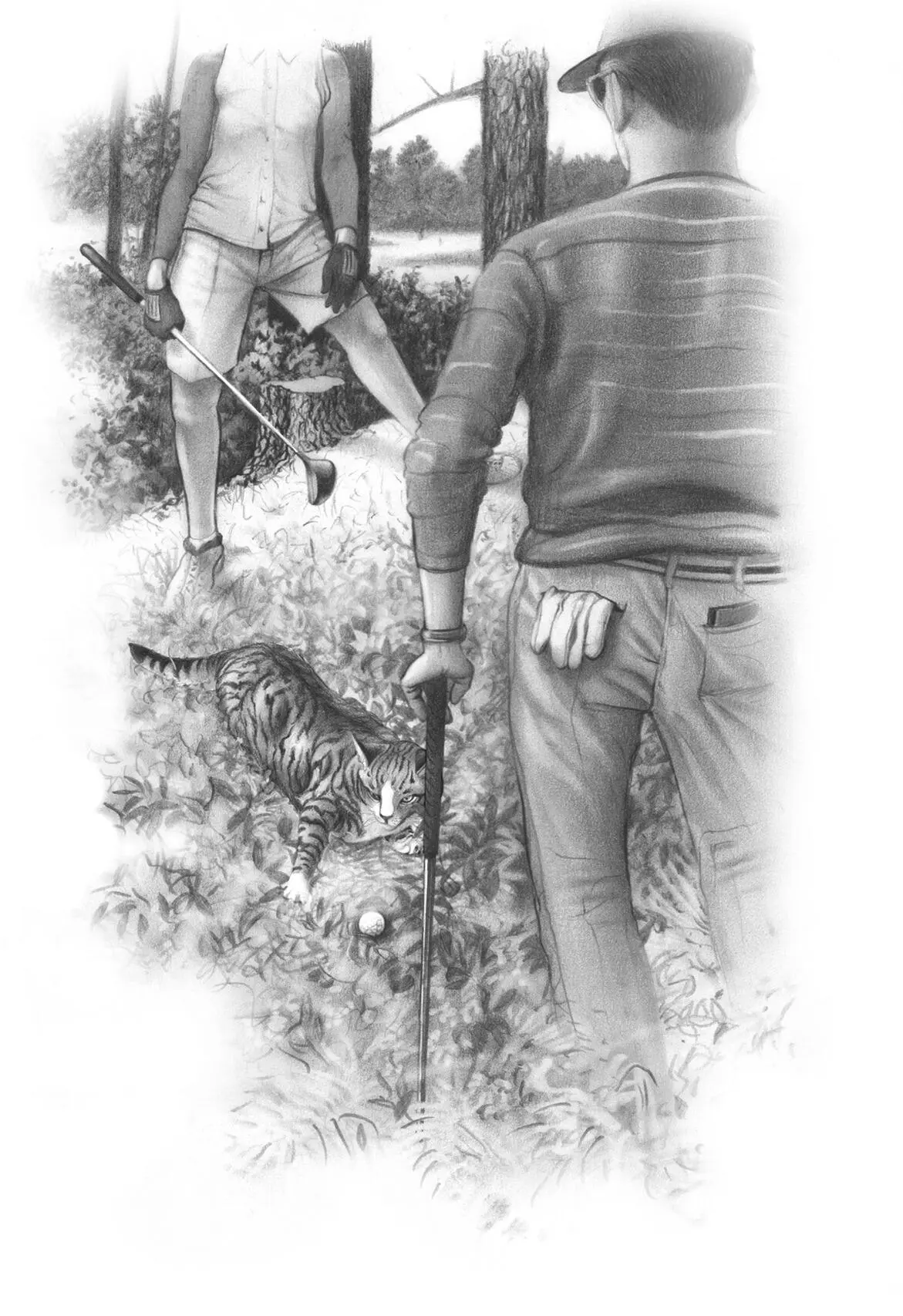

Marshall, on the other hand, cussed a blue streak in the woods. Harry, taking pity on him, went in to look too. The cats, the best scavengers of all, trotted after her, their tails straight up.

“I knew it,” he fumed. “I knew the minute I hit it that it was mishit.”

Harry prudently said nothing but continued to search. She saw the sawed-off trunk where she’d found the spike marks right after Ginger’s murder. She walked up to it. The cats continued the ball search.

“Harry, I don’t think I hit it that far,” Marshall called out.

“Right, I was just looking at something.” She walked back to continue the search.

“Found it,” he said, relieved.

“I found it first,” Mrs. Murphy corrected Marshall, as she was sitting right next to the ball.

“Murphy, don’t waste your time. Humans are notoriously ungrateful.”

Hands on his hips, Marshall mournfully squinted, looking through the trees. “I haven’t got a prayer.”

“It’s a Houdini shot,” Harry concurred.

“I’ll take the penalty stroke. Otherwise, I’ll waste ten minutes of everyone’s time.”

—

The rest of the afternoon passed pleasantly enough. Marshall shot in the low nineties. As just lately he played little, he was happy enough—rusty, but he could work on that.

Nelson came in fifteen over par, right on his handicap so he, too, felt he would improve. It was the beginning of May. Lots of time.

Susan shot an 83. Immediately after the game, she was already replaying every hole in her head, figuring where she made a mistake, where she could shave a stroke.

They all sat outside at the Nineteenth Hole. A bit cool, they wore their jackets but enjoyed the beautiful patio views of the golf course. The two cats nestled under Harry’s chair, alert to anything dropped.

“Feels good to be back out again,” Marshall said as his hamburger was delivered. “So much has been going on, I haven’t played for two weeks.”

“Has been intense,” Harry agreed.

“Thank you for helping me search for my ball back there on the twelfth. What a rotten shot.” Marshall pulled a face.

“I wasn’t but so much help, I got distracted by a stump in there.”

“Harry, not that again.” Susan rolled her eyes.

“Are we missing a good story?” Paul Huber smiled. “You know, a remembrance from your wild youth on the twelfth hole?”

“No, after Ginger was killed, I couldn’t help myself and I dragged Susan out to crawl over the twelfth hole and the holes close to it. I found spike marks on this clean-cut stump, the toes of which pointed in the direction where Ginger stood.”

“And I told her how lots of people get up on that stump to look for a lost ball,” Susan replied.

“If I’d known that, I would have gotten up there,” said Marshall. “Might have found my ball sooner.”

“Harry, you really can’t help yourself, can you?” David teased her. “You’ve watched too many mystery and crime shows.”

“I know. I know.” Then, to defend herself, Harry said, “But I think this all has something to do with The Barracks, the prisoner-of-war barracks.”

They fell silent, staring at her.

Finally, in a polite voice, Rudy responded, “Going from 1779 to today is quite a leap.”

“I know.” She grinned mischievously. “But if it’s true, what a story.”

In the spirit of the teasing, David said, voice commanding, “As an accountant, I can tell you without a doubt, it has to be about money.”

This got them all chattering.

Susan said, “Whatever happens, Harry will blame it on the cats or Tucker. You know, the cat found a bracelet or whatever. She can’t admit she is nosy beyond belief.”

“Hey, my dog and the cats did find Frank,” said Harry.

Again the conversation stopped.

“I had heard that,” Rudy replied. “Maybe it’s best we don’t think about it with our food.”

“Hear, hear,” David seconded the thought.

—

Later, walking back to their carts, out of earshot of Harry, Marshall whispered to Paul, “Where does she come up with this stuff?”

Paul shook his head. “I don’t know. But it would make a hell of a story.”

The cats, on their way to the truck, took a different view.

“She should keep her mouth shut,” Mrs. Murphy grumbled.

“True. She just opens that mouth and out spills whatever.” Pewter leapt onto the truck seat as Harry opened the door. “But here’s the thing, what if a murderer, THE murderer, sitting at another table, overheard her?”

“She’s asking for trouble,” the tiger sagely meowed as Harry cut on the motor.

“If she gets in trouble, that’s one thing. But she’ll drag us through it, and that’s another,” prophesied Pewter.

August 1, 1781

“It’s so bloody hot even the mosquitoes aren’t biting,” Edward Thimble cursed.

The men had their shirts off. Sweat rolled down their chests and backs as they carefully fit thick planks onto the last bridge over the ravine.

The bridges toward the barracks, traversing the gullies and the ravine, had been constructed with a mild arch to bear more weight. The task took longer than Corporal Ix anticipated. Delays, while not uncommon in any form of building, rarely bring out the best in people. The men cursed the heat, cursed the long grinding war, and finally cursed one another.

While laying the planks took care—no large gaps should occur—it was still easier than sinking the support beams and positioning the cross beams between them. Three men had broken bones. No one had died, but the incidence of heatstroke, abrasions, and exhausted muscles took its toll.

Charles worked alongside the men. Piglet slept under a large walnut tree, where he had been told to stay. Charles wistfully looked at his dog, wishing he were sleeping there, too.

The men, American and British, knew the French had arrived at Newport, Rhode Island, good news for the rebels. Charleston, South Carolina, had been captured by the British and the Continentals were crushed at Waxhaw Creek, South Carolina.

Despite Mad Anthony Wayne’s being beaten back at Green Springs Farm, east of Charlottesville, the rebels grew more confident. The sheer landmass of the colonies, as well as the territories inland, meant the British would need to commit thousands and thousands of men for victory. And after they won, they would need thousands and thousands of men to keep the peace.

Charles, receiving scant letters from home, more from his elder brother than his father, knew that Lord North’s sufferings continued, intensifying unpopularity. His brother, much shrewder about politics than their father, wrote that sooner or later North’s government would fall. The British people were weary of a war that was to have been swift. They didn’t much like the increased tax burdens. If the colonists wanted to go, let them. The British still held New York, Savannah, and Charleston, but they no longer controlled Philadelphia, the largest city in the New World. The victories they won had little effect upon the rebels, who kept on fighting, wearing down the invaders. Reputations were ruined; a few were made, but very few. Those men who hoped to rise from this war, receiving larger commands and financial reward from a grateful king, had long since realized little gratitude was forthcoming.

Читать дальше