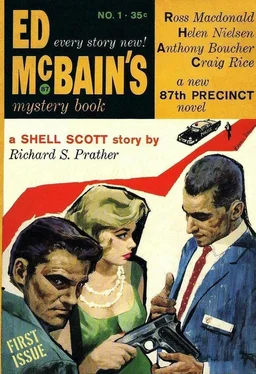

Anthony Boucher - Ed McBain’s Mystery Book, No. 1, 1960

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Anthony Boucher - Ed McBain’s Mystery Book, No. 1, 1960» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1960, Издательство: Pocket Books, Жанр: Детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Ed McBain’s Mystery Book, No. 1, 1960

- Автор:

- Издательство:Pocket Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1960

- Город:New York

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Ed McBain’s Mystery Book, No. 1, 1960: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Ed McBain’s Mystery Book, No. 1, 1960»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Ed McBain’s Mystery Book, No. 1, 1960 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Ed McBain’s Mystery Book, No. 1, 1960», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

If there is another major conflict, it is expected that, along with the forging of passports, identity and ration cards, and military documents, the currency of enemy nations will be counterfeited on a vast scale. It is an accepted ruse of war.

Agents of the United States Secret Service, one of whose major jobs it is to nail the counterfeiter, regard him a great deal less tolerantly than the public. Apart from his effect on the monetary system, he is indirectly a recruiter of criminals. The Secret Service ranks him in the company of the kidnaper and dope peddler.

A worth-while counterfeiting operation in America today involves various specialists. A money man lays out about three thousand (genuine) dollars for equipment — photoengraving machinery, a single-color press, etching and routing machines. After a batch of money has been made, the money man sells it to a wholesaler for about eight cents on the dollar. The wholesaler sells it to retailers for twenty cents on the dollar. Passers buy it for thirty-five cents on the dollar.

Passers are the most vulnerable link in the entire operation. Many of them are known to police and Secret Service agents. They are the petty crooks whom shopkeepers will finger as the shover of a particular phony bill.

So the passer depends on his wife or sweetheart to do some of the work — the psychology being that a chivalrous bartender will not inspect a bill received from a lady as closely as that from a man. Should she be nabbed, if she has a clean record, she can indignantly claim that she is the dupe of some crook, and who can deny it?

But when a passer is far away from his loved ones, he must rely on strangers for help. A common procedure is for him to wander up to an idle young man with an alert look, offer him a cigarette, and chat awhile. Then, explaining he got stuck with a bogus banknote, he asks the young man — called a lobby guy in counterfeiting circles — to try to buy something with it. Should the lobby guy succeed, he is promised a great deal of change for his errand. If he gets nabbed, he is a first offender, can claim to be a dupe, and is relatively safe. But he is not so safe as the passer, who, at the first sign of suspicion on the part of the recipient of the money, darts to another corner of town. However, it is often a fine opportunity for a young man with an honest face and a charming manner to get a foothold in crime.

The paper-money creator himself, on whose skill the success of passers and their tools largely depend, has the ego, generally, of a top-flight artist. Extremely few counterfeiters are women; they are mainly small, uncommunicative men who think themselves far superior to coin counterfeiters — those shoestring operators whose margin of profit is so tiny they must do their own passing with a pocket full of change.

Whether counterfeiters are of high or low caste in the great scheme of things, they have furnished more bold, wily, and capricious oddballs than any other branch of crime.

A Russian gang in 1912 circulated half-ruble notes which were excellent reproductions of the Czar’s highly inflated currency, except that on the bottom of each note was the wry message, “Our money is no worse than yours.” Emanuel Ninger, a New Jerseyite who traced paper money on fine bond paper after it was soaked in coffee, was arrested when one of his fifties got wet from lying on a bar. He claimed to police that he was not legally a counterfeiter because he left the phrase “Bureau of Printing and Engraving” off his hand-drawn notes. Marcus Crahan solved the problem of getting nabbed with the curly — always embarrassing for a counterfeiter — by pointing to an ad he repeatedly put in the paper. It said he had found a bundle of money which the owner could claim on proper identification. The Secret Service was skeptical and he eventually got fifteen years.

A Louisiana justice of the peace in 1908 set up a counterfeiting plant in a room near his court. When culprits paid fines and got change, the change they got was counterfeit. A personable Midwesterner of the nineteenth century, Thomas Peter McCartney, lectured under the name of Professor Joseph Woods. His subject was the art of detecting counterfeits. But he was prudent enough not to reveal how to distinguish the counterfeits McCartney was putting out; he talked only about his competitors. A Milanese counterfeiter of American tens made a self-conscious commentary on the quality of his merchandise when he left out the first L in the third word of the phrase, “Redeemable in Lawful Money.”

Coiner Edward Berglund, who was enchanted by slot machines, fed them his own fifty-cent pieces. When he was caught, he insisted that what he was doing was legal because he had printed the word “slug” on every one of them. Forrest Starling, of Perry, Iowa, minted phony fifty-centers, using a homemade die and putting more silver into his coins than the United States Mint puts into its fifty-centers. Bold as brass, he passed some of them in stores in Leavenworth before a bank clerk noticed that the reeding (the grooved outer edge) was deeper than the Government’s. Secret Service agents made inquiries and arrested him. When asked why he made his reeding so deep, he haughtily replied they were his coins and that was the way he wanted them.

Bogus-money men, in the United States at least, are growing less colorful and less successful. Since 1863, when one third of the money in circulation was counterfeit (a situation brought about because of the huge number of state and “wildcat” banks), the amount of phony money in circulation has been chopped down to an infinitesimal proportion. This has been mainly because of the work of the Secret Service, established in 1865. Of the $30,000,000,000 in circulation today, only one one thousandth of one per cent is counterfeit. In the fiscal year 1959 agents of the Service — dogged shadowers and ingratiating mixers with crooks — captured nineteen plants for the manufacture of fake paper money. The total value of money seized was $1,923,536; only $260,329 of it got into circulation. Of $6,766.32 in phony coins, $6,359.07 got into circulation, but the Secret Service does not regard the coiner as a menace.

The record for the rounding up of a counterfeiting ring and the seizure of its equipment is eight hours. A few years ago, a grocer in Pittsburgh received a phony five-dollar bill and happened to notice that the woman who gave it to him got into a car with New Jersey plates. Remembering the license number, the grocer passed it along to Secret Service men, who checked it with authorities in Trenton. It developed that the car owner lived in Centreville. A few hours later an agent was on his way there, accompanied by a New Jersey state trooper. When they arrived at the house, the two pounded on the door but failed to wake anyone, so the agent went around back. He glimpsed a man in pajamas who was flourishing a shotgun. Busting in, the agent snatched it from him, kicked down a wall and found a set of plates, and turned the man over to the trooper.

Then he waited for the lady to return. She came in the car, along with a man. The agent blew a hole in the front tire, yanked the door open, and braked the car. It was filled with minor purchases bought with the phony money the afternoon before. Two trunks filled with counterfeit were located in the attic and two more plates were found hidden in the rafters. The three, comprising the entire gang, were taken into custody and the case was wrapped up. The Secret Service man, who had been sick, went back to bed.

There are fashions in forgery and counterfeiting just as there are in dresses and hats. Supply follows demand. Ancient Romans bought ancient Greek sculptures and coins that were forged. The Middle Ages, eschewing art, specialized in the counterfeiting of relics of saints and martyrs. During the Renaissance classical sculpture was admired; it naturally followed that it was forged. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries picture faking was the rage, while in the eighteenth, emphasis shifted to romantically inspired literary works, such as James Mac-Pherson’s “translations” of the poems of Ossian, a legendary third-century bard. Thomas Chatterton wrote a “play by Shakespeare” — Vortigem — which was produced in 1796 but was unfortunately howled off the stage. The golden age for antique forgery, as well as forged works of art of all types, was the nineteenth century. Expert criticism was rare and scientific detection methods were still in their infancy.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Ed McBain’s Mystery Book, No. 1, 1960»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Ed McBain’s Mystery Book, No. 1, 1960» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Ed McBain’s Mystery Book, No. 1, 1960» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.