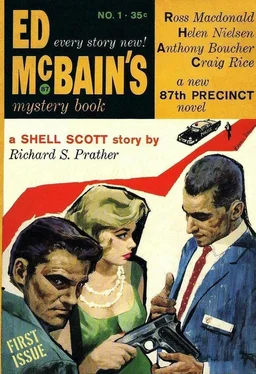

Anthony Boucher - Ed McBain’s Mystery Book, No. 1, 1960

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Anthony Boucher - Ed McBain’s Mystery Book, No. 1, 1960» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1960, Издательство: Pocket Books, Жанр: Детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Ed McBain’s Mystery Book, No. 1, 1960

- Автор:

- Издательство:Pocket Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1960

- Город:New York

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Ed McBain’s Mystery Book, No. 1, 1960: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Ed McBain’s Mystery Book, No. 1, 1960»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Ed McBain’s Mystery Book, No. 1, 1960 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Ed McBain’s Mystery Book, No. 1, 1960», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“You don’t look so hot,” Joe the Angel said thoughtfully. “You want me to leave the bottle?”

Malone sighed. “Don’t be ridiculous,” he said. “Then I wouldn’t have anybody to talk to.” He closed his eyes and tried to think. This Littleton had been hard-working, honest, and seventy-five thousand dollars in debt. Hook hadn’t killed him, and Cowperthwaite hadn’t killed him, and his wife hadn’t killed him, and he hadn’t committed suicide. The whole thing was terrifying.

“I’m glad I found you,” von Flanagan was saying. “You’re drunk, but I’m still glad I found you. I want to tell you you’ve been wasting your time. We thought there was a connection between the salesmen. But there isn’t.”

“You’re wrong,” Malone said magnificently. “But go on anyway.”

“Tallmer,” von Flanagan said, ignoring the interruption. “The first one. A guy walked into the station-house and said he was the hitter-and-runner. Conscience was bothering him. And there was no connection between him and the rest. Accidents. Like we figured.”

“Wrong,” said Malone sadly. “Completely wrong.”

“Huh?”

“I’ll explain,” said Malone. “I will tell all. I sort of thought something like this would happen.” He sighed. “Tallmer was a typical hit-and-run. That much you know.”

“That much I just told you.”

Malone nodded. “Prince and Kirschenblum—”

“Kirschmeyer.”

“To hell with it,” said Malone. “Anyway, the two of them were murdered. By the same person who killed Littleton.”

“If you’re so smart,” said von Flanagan, “then you can tell me that person’s name. The one who killed them all.”

“Simple,” said Malone. “The name is Littleton.”

He explained while von Flanagan sat there gaping. “Littleton was in debt,” he said. “Seventy-five grand in debt. With no way out. Then Tallmer got hit by a car.”

“Precisely,” said von Flanagan.

“And Littleton got an idea,” he said. “He wanted to kill himself but he didn’t want his wife to lose the insurance. So he killed himself and made it look like murder.”

Malone lit a fresh cigar. “He set up a chain,” he went on. “Chucked Prince down an elevator shaft and heaved Kirschengruber in front of the elevated.”

“Kirschmeyer.”

“You know who I mean. Anyway, Littleton did this, and set up a chain. A subtle chain. Then he shot himself.”

“Left-handed? From a distance?”

“Of course,” Malone said. “If you wanted to make it look like murder, would you use your right hand and put the gun in your mouth? See?”

Von Flanagan thought it over. “So it’s suicide,” he said. “And we write it off as murder and suicide, with Littleton the murderer. Right?”

“Wrong,” Malone said. “You write Prince and Kicklebutton off as accidents and Littleton as murder by person or persons unknown. If he went to all that trouble there’s no sense in conning the wife and kids out of the insurance. Besides, you’d never get a suicide verdict. Not unless I persuaded the coroner’s inquest. And I won’t.”

Von Flanagan shrugged. “How are you going to collect your fee?”

“I’ll tell Gunderson his salesmen are safe,” Malone said. “I’ll offer to repay the fee in full if another one gets murdered. And if that’s not enough for him, he can keep the twenty-five hundred he owes me. Remember, I didn’t want this case in the first place.”

Reasonable Facsimile

Rex Lardner

Forgers and counterfeiters, as a class, are the most versatile of crooks and very likely the most persistent. While their creative skills differ — some relying on the gullibility of the public and others grimly trying to baffle the experts — they are an audacious, generally conscientious lot, proud of their artistic calling.

Some are quite whimsical. A check forger in California obtained cash for a check he signed “I. Nogota.” Other signatures similarly honored have been U. R. Stung and N. O. Funds. Still another practitioner of what is called white-collar larceny received money for a check drawn on his account in the East Bank of the Mississippi.

Despite care, some make slips. A short, toothless New York paper-money counterfeiter named Edward Mueller spelled the name of the first President wrong on his one-dollar bills. He spelled it WAHSINGTON. It should have been a tipoff to the recipient that he was getting Brand X money, but the Secret Service observes sadly that few people peer closely at a one-dollar bill.

A few count on the blind enthusiasm of hobbyists. Letters from Cleopatra to Mark Antony and from Socrates to Euclid have been sold to collectors of such historical treasures, considered the more valuable, perhaps, because they were written in French. An enterprising salesman of Buffalo Bill pictures — like those formerly sold at Wild West shows — shot them up to five times their worth by ingeniously signing Buffalo Bill’s name on them, using a ballpoint pen.

The dissimulation practiced by these rascals, driven by some irrepressible urge to challenge credulity, extends to nearly every field of human endeavor — art, archaeology, the sciences, literature, philately, autograph collecting, show business, gambling, and commerce. Whatever man hath wrought, going far back into the recesses of time, another man has sought to imitate — for self-satisfaction, out of resentment or frustration, or to earn money.

Throughout history people have been duped by phony statues, “undiscovered” plays and poems by famous authors, spurious Mona Lisas, fake rare coins, false wills, doctored documents, reed-filled mummies, bogus antiques bored by counterfeit worms, fraudulent first editions, tapestries, and old bones. And scores of other products: objets d’art, fossils, collectors’ items, and legal instruments.

The balance today is weighted less toward stone axes and lace than toward forged sweepstakes tickets, race-track tickets, liquor stamps, and orchestra seats for hit musicals, but the art has not died out. As befits the present age, characterized by our preoccupation with advertising, automobiles, and commerce unsullied by the use of cash, today’s booming forgeries are in the fields of trademark reproduction, auto licenses, and personal checks.

It is an oddity of human nature that while pickpockets arouse our disdain and muggers our fury, we are quite tolerant of most persons engaged in criminal fraud, forgery, and counterfeiting.

Perhaps it is because they are intellectual crimes, proving, in the area of shrewdness anyway, the superiority of man over the apes. Perhaps it is because the wily perpetrators of these offenses appear to be loners, valiantly pitting their wits against experts, bureaucrats, and other entrenched specialists whose dignity it is pleasant, now and again, to see punctured.

Another reason might be that duplicity of one sort or another is practiced in many legitimate business operations, in politics, diplomacy, the drama, and poker. Forgery, in its various guises, becomes merely a formalized and more dangerous projection of the art of deceit.

In the case of counterfeiting money, moreover, it is likely that most of us suffer from pangs of conscience and can identify, to a degree, with that familiar of the funny-money manufacturer, the passer. Having got stuck with a phony fifty-cent piece or five-dollar bill, we are roguishly tempted to sting someone else with it. This is preferable, certainly, to turning it in to the police, as the law demands, and a) accepting the tacit label of sucker and b) losing the value of the money.

For the successful forger of paintings, such as the late Hans van Megeeren, who in the 1940’s drew and scientifically aged “Vermeers,” we feel not admiration but awe. Here was a much-scorned artist, a tiny man with the knowledge and skill to make complete idiots out of the haughty art experts! In fact, although Van Megeeren confessed the forgeries and outlined in detail how and where he committed them, some critics keep insisting that Vermeer must have painted some of the Van Megeerens. There can be no higher tribute to a forger.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Ed McBain’s Mystery Book, No. 1, 1960»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Ed McBain’s Mystery Book, No. 1, 1960» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Ed McBain’s Mystery Book, No. 1, 1960» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.