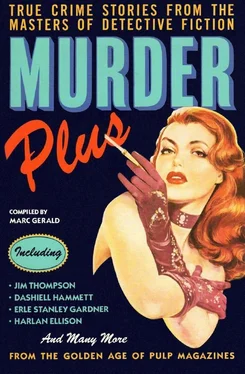

Харлан Эллисон - Murder Plus - True Crime Stories From The Masters Of Detective Fiction

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Харлан Эллисон - Murder Plus - True Crime Stories From The Masters Of Detective Fiction» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1992, ISBN: 1992, Издательство: Pharos Books, Жанр: Детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Murder Plus: True Crime Stories From The Masters Of Detective Fiction

- Автор:

- Издательство:Pharos Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1992

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-88687-662-3

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Murder Plus: True Crime Stories From The Masters Of Detective Fiction: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Murder Plus: True Crime Stories From The Masters Of Detective Fiction»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Murder Plus: True Crime Stories From The Masters Of Detective Fiction — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Murder Plus: True Crime Stories From The Masters Of Detective Fiction», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Sergeant Sperling went over the broken pieces of the bottle for fingerprints,” Herrick reported. “He found about what we expected — the prints of Mr. and Mrs. Engleberry and one of the milkman, Will Hitch. On a night as cold as last night, practically everybody wore gloves.”

“How about the New York City end?” District Attorney Simms inquired. “Miss Lahey worked there and most of the people she knew, it seems, live there.”

Herrick nodded. “I spoke to the New York Homicide Bureau on the phone. They promised full cooperation. All the men she’s known in New York are being investigated.” He sighed. “But I hardly expect anything to come of that. I am convinced that the murderer did not come all this way to murder her. The crime shows all the marks of having been impulsive, unpremeditated.”

“And Shanken admitted he had been out with Miss Lahey last night,” Simms rubbed his lean jaw. “He’s our man.”

For brief moments they sat about the desk in silence. Then Herrick said glumly, “You’re the District Attorney. Can you prove Shanken guilty in court? Have you even enough to indict?”

“Well, no,” Simms admitted. “Not yet, at any rate.”

Shortly after the District Attorney and the Coroner departed, Sergeant Sperling entered the office with a cardboard box under his arm. Within the box, the white plaster cast of the footprint was carefully protected by excelsior.

“The casts are finished,” Sperling announced. “I made three. I’m sending Mike Rossi to New York with one. Now what shoes do we look at?”

Herrick had not mentioned the cast to the District Attorney. He was afraid it wouldn’t be taken seriously; he wasn’t sure himself whether or not to take it seriously. But Sperling believed in what he was doing, and there was nothing to be lost by following through.

“Try Shanken first,” the Chief told him.

It was almost time to knock off for supper when a dumpy little man walked into Police Headquarters and introduced himself to Herrick as Dwight Braun, the radio agent.

“Say, what’s the idea of sending the cops after me?” he demanded. “I’m minding my own business when a couple of detectives barge in on me and ask all kinds of questions about Vivian Lahey’s murder. That was the first I heard of it. They acted as if I’d killed her.”

Herrick grunted with satisfaction. The New York police were wasting no time.

“Did you kill her?” he asked softly.

“Don’t be a sap!” Braun spread his plump body on a chair and set fire to a cigarette. “The minute those cops left, I drove out here to let you know what happened last night.” And he told substantially the same story as the Engleberrys.

“Did you drive out to Marvin Center in your car last night?” Herrick wanted to know.

“Sure. The train connections out of this place are terrible, especially at night.”

“Let me get this straight,” Herrick said. “Miss Lahey was in New York more than she was here. Yet you took this trip late at night, when you could as easily have seen her in the city?”

“Who says so? The point is, Vivian decided to get another agent after all I’d done for her, and then she wouldn’t even discuss it with me. Maybe she wasn’t a top-notch singer and maybe she would never have been, but the ten percent commission I made on her was worth spending an evening on.”

“And after having come all this distance you left without seeing her.”

“I was sore, I’d phoned Vivian beforehand and she’d said she’d be home, and then she left before I arrived and hadn’t returned by eleven. She wasn’t enough of a big-shot for me to take that from her.”

Herrick toyed with his pencil. “Did you wear rubber shoes last night?”

“Huh? What for? The sidewalks were clean. At least in New York they were.”

The Chief went out and returned with the third plaster cast of the footprint. While Braun watched in bewilderment and flung questions at Herrick, the latter got down on his knees and carefully placed the agent’s shoe in the cast. Braun’s foot was almost womanish in its smallness; there was a good inch to spare at the toes. The Chief didn’t have to compare the heel markings to know that Braun’s foot had never made that print.

As Herrick clambered back to his feet, he saw Sperling standing in the doorway with the cardboard box under his arm and an amused smile on his lips. “That man’s foot is too small, Chief. I could’ve told you without measuring.”

Herrick gave the Sergeant an annoyed look and retreated behind his desk. “You can go,” he told Braun wearily.

“Does that mean I won’t be bothered any more?” the agent demanded.

“It means you can go now,” the Chief said snappishly. He was annoyed with himself at discovering that his nerves were on edge.

When Braun had gone, Sperling advanced into the office and placed the boxed plaster cast on the desk. “I drew a blank myself, Chief. John Shanken’s shoes weren’t the right size either. I went to his store and he made no fuss while I matched his shoe. His foot is too big by at least a size, so I didn’t bother going to his house to look at his other shoes.”

Herrick studied his fingernails. “You know more about these scientific methods than I do, Ray. How much confidence have you that footprint means anything?”

Sperling hesitated before answering. “If the murderer made that footprint, then Shanken is out.”

“If!” Herrick echoed. “That’s the trouble. You may be able to show that that footprint was made after the murder and not before. But you can’t prove to a jury’s satisfaction that it’s the murderer’s.”

“Well, Chief—” Sperling obviously did not want to put himself out on a limb. “If Shanken had made that footprint, it would at least prove that he had gone to the back door with Miss Lahey.”

“But it doesn’t prove that he didn’t,” Herrick muttered. He stood up in sudden decision. “Come with me, Ray. And bring that cast.”

They drove to 37 Oak Lane. Rose Engleberry was home alone. Evidently she had not dressed all day, for she still wore her nightgown and a robe and slippers. In ten hours she seemed to have aged ten years.

“When do you expect your husband home?” Herrick asked her.

“Usually he gets home a little after six, unless he works overtime,” she replied listlessly. “Do you want to wait for him?”

“You’ll do just as well. I’d like to get the events of last night clearer in my mind. You say you went to bed at about eleven?”

Her plump shoulders shrugged. “Around then. I’m not certain of the time, except that it was right after Dwight Braun left.”

“And your husband went to bed with you?”

She sat back in the corner of the couch and looked curiously at the Chief. “Why do you ask that question?”

“I’m anxious to pin down the time of the murder. I imagine it was after Mr. Engleberry went to bed or he would have heard something.”

“As a matter of fact, George stayed up a little while longer. He wanted to finish reading his paper.”

“Did you hear him go to bed?”

“No. I fell asleep practically at once. And as we have twin beds—” She stopped. A shadow crossed her face. “Why don’t you ask George?”

“I will,” Herrick said dryly. “Now, Mrs. Engleberry, I have a favor to ask. We found a footprint outside in the snow. If it belongs to Mr. Engleberry, whose footprints would naturally be all around the house, then we can eliminate it from consideration. May we see your husband’s shoes?”

She took some time to consider the request, then said doubtfully, “George, of course, is wearing a pair of his shoes. Hadn’t you better wait till he comes home?”

“We’re in a hurry. All we want to do is measure any of his shoes for size.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Murder Plus: True Crime Stories From The Masters Of Detective Fiction»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Murder Plus: True Crime Stories From The Masters Of Detective Fiction» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Murder Plus: True Crime Stories From The Masters Of Detective Fiction» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.