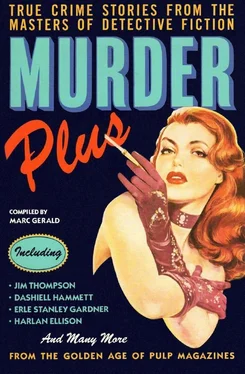

Харлан Эллисон - Murder Plus - True Crime Stories From The Masters Of Detective Fiction

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Харлан Эллисон - Murder Plus - True Crime Stories From The Masters Of Detective Fiction» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1992, ISBN: 1992, Издательство: Pharos Books, Жанр: Детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Murder Plus: True Crime Stories From The Masters Of Detective Fiction

- Автор:

- Издательство:Pharos Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1992

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-88687-662-3

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Murder Plus: True Crime Stories From The Masters Of Detective Fiction: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Murder Plus: True Crime Stories From The Masters Of Detective Fiction»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Murder Plus: True Crime Stories From The Masters Of Detective Fiction — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Murder Plus: True Crime Stories From The Masters Of Detective Fiction», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“If we find the shoe,” Herrick observed dryly.

A black cloth handbag lay near one of the dead girl’s gloved hands. Herrick looked through it. He found a wallet containing eighteen dollars. Obviously the motive for her murder hadn’t been robbery.

Patrolman Byron came up the driveway with the information that the woman next door, in Number 39, had heard two people fighting outside during the night. Herrick felt his shoulders lighten a little. Here, at last, was a witness. He hurried to the house next door.

Mrs. Tracy M. Anderson, a fading middle-aged blonde, wearing a cloth coat over her house dress, was watching the crowd that was gathering by the minute in front of Number 37.

“Well, I’m not sure it was exactly a fight,” she said. “But the voices sounded like a quarrel.”

“Did you recognize the voices?” Herrick asked.

“Well, one was Vivian Lahey’s, I suppose, but all I can be sure of is that it was a woman’s voice. You see, I was in bed, more than half asleep, when those voices woke me up. The bedroom is on that side of the house, right next to the Engleberry driveway. I heard a kind of muttering at first, then the voices rose but I can’t tell you who the man was, even if I’d ever heard his voice before.”

“Did you hear what was said?”

“No. Just voices. Then I fell asleep. I told that other policeman who was here that I didn’t hear anything else — no cry or anything like that. I just fell asleep in the middle, I guess. And I can’t tell you what time it was. All I know is it was night.”

“What time did you go to bed?”

“A little before twelve,” Mrs. Anderson replied. “Me and my husband both. The children were in bed since ten. But Tracy — that’s my husband — he didn’t hear a thing. He sleeps like a log.”

“Where’s your husband now?”

“He left for work a little while ago. But he didn’t hear anything. We talked about it when we heard poor Vivian Lahey was murdered. That was when I remembered hearing those voices. I said to Tracy—”

Mrs. Anderson went on talking, but she had no more to contribute. Herrick was satisfied that she had given him vital information. Vivian Lahey had quarreled with the man who had murdered her, which meant that she had known him well. And likely the murder hadn’t been planned, but had resulted from the quarrel. A milk bottle was the sort of weapon one would snatch up in a fit of overpowering rage.

John Shanken scowled when the Chief entered his haberdashery store.

The clerk stepped up to Herrick, “What can I do for you, sir?” But before the Chief could reply, Shanken waved the clerk aside and beckoned Herrick into the back room of the store.

Shanken was an athletic-looking man in his late thirties. He dressed like a fashion-plate, as befitted a man who sold men’s wear, and sported a sleek mustache. Herrick recalled that Shanken, in spite of a wife and three children, was considered quite a lady killer.

The Chief asked casually, “Have you heard what happened to Vivian Lahey?”

“The news is all over town.” Shanken had trouble finding a place to rest his gaze. He shuddered. “Terrible tragedy! She was such a fine girl.”

“A friend of yours, I hear.”

The haberdasher shrugged. “Oh, well, I knew Miss Lahey as a good customer. She bought all her Christmas and birthday presents for male relatives and friends in my store.”

Through narrowed eyes, the Chief studied the man. There was no doubt that he was badly frightened. He hazarded a guess. “Where did you go with Miss Lahey last night?”

It worked. Shanken’s head jerked up; the fear in his eyes was plain. “I didn’t kill her! I swear—”

“Where did you go with her last night?” Herrick repeated.

Shanken dropped limply into a chair. “I was going to tell you. I’d just heard of the murder and I was about to go to the police station when you came in.”

“Were you?” Herrick grunted skeptically. “All right, tell me now.”

“She... I... well, we’ve been seeing each other. Secretly. Look, Herrick, there’s nothing to be gained by letting my wife know.”

Herrick felt an unpleasant taste in his mouth. “I can’t promise you anything. It depends on whether you’re innocent and how completely honest you are with me.”

“I’ve nothing to hide from the police,” the man insisted. “But if my wife should find out — well, the scandal—” He shook himself and went on, “Vivian hasn’t let me see her for three weeks. I went almost crazy. She is — she was a very lovely girl. Last night I phoned her.”

“At what time?”

“Around nine. A little after.”

“As late as nine-thirty?”

“It may have been. I told Vivian that if she didn’t at least come out and talk to me for a few minutes, I’d barge into her house. She gave in grudgingly and I picked her up in my car on the corner of Oak Lane and Lanning Place. We drove and parked and drove some more while I kept arguing with her.”

“How long?”

“What? Oh, hours.”

“In the cold?”

“I’ve a heater in my car,” Shanken replied. “Vivian said that people were talking about us and that we mustn’t see each other again. I couldn’t give her up. She was in my blood. I argued and argued. I—” He broke off and hunched his shoulders. “It was no use, so after a while I drove her home.”

“What time was that?”

“I don’t know. Around midnight.”

“Can you fix the time closer than that?”

Shanken was thoughtful, and then shook his head. “I’m afraid not. I was very upset. I didn’t bother to look at the time. I’m sure it was at least twelve. Maybe a few minutes later.”

Herrick was ready to spring a trap. He asked with apparent indifference, “What happened when you walked to the back door of the house with her?”

“I—” Shanken took a deep breath, “I didn’t get out of the car with her. By that time we were both pretty sore at each other. When I pulled up in front of Vivian’s house, she got out of the car and slammed the door. I drove home.”

“Just like that?” Herrick said grimly.

“I tell you I did. I wouldn’t hurt a hair of her head.”

“You said you were sore at her.”

“But not enough to kill her. Why would I want to kill her? That would be crazy.”

“Crazy,” the Chief muttered. “By the way, did you wear rubbers or galoshes last night?”

“I never wear galoshes. They look frightful. Rubbers sometimes, but—” He frowned up at Herrick. “I don’t understand the question.”

“All the same, I want an answer. What did you wear on your feet last night?”

“Just my shoes. The garage is under my house. I didn’t have to walk in the street.”

At any rate, that was Shanken’s story and he stuck to it. Herrick debated with himself whether to take him to Headquarters for further questioning, and decided not to. He hadn’t enough on the man to hold him and would only succeed in putting him on his guard. In a place the size of Marvin Center, where Shanken was a businessman of considerable importance, it was necessary for the police to feel their way carefully.

As the day wore on, the responsibility of the case piled on Herrick’s shoulders. He knew that the whole town — indeed, the whole county — was watching him. This was the first big test in his nine years as Chief of Police.

In the late afternoon Arthur Simms, the District Attorney, and Dr. Everett J. Ames, County Coroner, came to his office for a conference.

Dr. Ames had his preliminary report. He agreed that Vivian Lahey had probably died between midnight and 1 A.M., but he could not give a definite statement until he had completed the post-mortem, which would be some time the following day. He had no doubt, however, that the blow with the milk bottle had killed her almost instantly.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Murder Plus: True Crime Stories From The Masters Of Detective Fiction»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Murder Plus: True Crime Stories From The Masters Of Detective Fiction» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Murder Plus: True Crime Stories From The Masters Of Detective Fiction» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.