A siren moaned in the distance, drawing nearer. I said, “Excuse me, sir, but I’m afraid we dropped something out that window a few moments ago. It landed down by the streetlight.”

“Bud, there’s an ordinance against dropping stuff out hotel windows. If it was hotel property, you got to make it good.”

My cornflower blonde had begun to comprehend. Her eyes looked faintly sick, but at the same time awfully glad.

The beef trust waddled over and stuck his head and shoulders out the window. He stiffened, and his wet lips made flapping sounds in the night. I paused behind him and looked, with a tinge of regret I must admit, at the general area where his pants were the tightest.

I put my hands firmly in my pockets. You’ve got to watch a thing like that. It can turn into a compulsion neurosis.

My lovely lassoed me with her big shining eyes, and I didn’t hear a yammering word the beef trust said, even though he was jumping clean off the floor every time he took a breath.

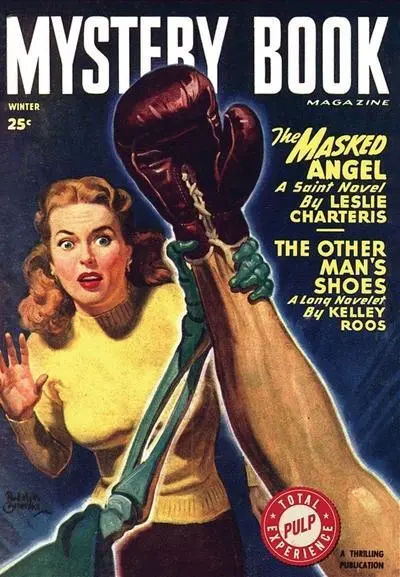

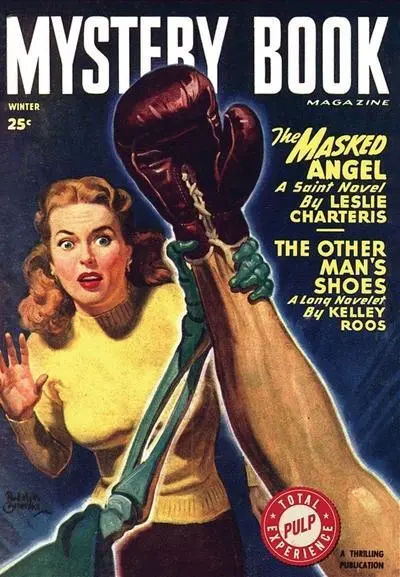

She was a plump blonde, and she lay dead in the trail on her back. There were streaks of drying mud on the right sleeve of her pale yellow sweater. There was more mud on her freckled right arm. Death had flattened her body to the ground. Her tweed skirt was pushed up halfway between knee and hip. Her heels rested in the mud and her brown sandals toed in.

The black trees, stripped naked by autumn, stood high around her, and the chill wind off the lake hurried the dry brown leaves across the trail. A leaf had stuck to her hair over the right temple, where the hair was sticky with new blood.

I would have guessed that when she was alive she was pretty and vivacious. Her lids were half closed, showing a semicircle of glazed bright blue.

Her husband, Ralph Bennison, or more accurately, her widower, had phoned Burt Stanleyson from the nearby village of Hoffwalker. Burt and I had climbed into the white County Police sedan and driven to Hoffwalker, where Bennison had been waiting in his car.

He had stopped on the state road opposite that part of Lake Odega where summer camps are clustered along the lakeshore.

We had followed him down the trail to the lakeshore, seeing ahead of us the spot of color against the brown earth — her yellow sweater.

I leaned against a tree and Ralph Bennison sat on a rotting log, his face hidden in his hands. Burt Stanleyson stood beside the body of Mrs. Bennison, staring down at it, while he chewed a kitchen match.

I couldn’t help noticing the differences between my friend Burt and Ralph Bennison. They were both big men. Burt wore a wrinkled gray suit and still managed to look as if he belonged in the woods. Perhaps it was the way he moved and the weather wrinkles that lined his brown face.

Bennison wore a red-and-black wool shirt with matching breeches and high shoes. But his face was white and he moved quickly and nervously. He had the city label on him, all the way from his big shiny fingernails to the bright new leather of his knife sheath.

Suddenly Bennison lifted his blotched face out of his hands and said in a tight voice, “Why are you standing around staring at her? Why aren’t you across the lake trying to find out who fired the shot?”

Burt gave him a steady look and then knelt beside the dead woman. He fingered the hair around the wound, dislodging the crisp leaf. I could see the hole in her head, neat and round. Burt reached down and gently pulled the tweed skirt down to cover her knees. He stood up again and poked with his toe at the mud caked on the sides of her brown shoe. He sighed. The wind swirled a dancing funnel of leaves down the trail.

If it happened in the summer, there would have been a crowd of summer folks standing around. But in November the camps are empty except for a few hunters, and they were still out in the woods after their deer.

Bennison stood up and glared at Burt, then scuffed the hard ground with the toe of his spotless high shoes.

“Look here,” he said. “Alice and I were walking down the trail with the lake at our right. She was ahead of me. The trail is muddy and uneven, and I was watching my feet, like I told you. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw her fall on her face. I jumped toward her, thinking that she had tripped. As I jumped, I heard a distant noise like a shot. I rolled her over and held her head in my arms. I saw she was dead, and realized that she had been killed by a stray shot. Then I came after you. Why aren’t you after those people across the lake?”

Burt said patiently, “Mr. Bennison, there are two dozen hunters in there. It’s four o’clock now. We couldn’t round ’em up before dark, and most of them will be cutting back to the other road and driving out of the woods. They’d deny firing high toward the lake. We’d have to take their guns away from them and fire a sample slug from each one. Then we’d have to dig the slug out of your wife’s brain and send the slugs down to a comparison microscope. It would be a colossal job. We’ll just have to give it a lot of publicity and hope that some man’s conscience will punish him.”

“The bullet sort of came down on her, didn’t it, Burt?” I asked.

“That’s right, Joe. Thirty-caliber. From better than a half mile, or it would have gone right through her.”

He turned to Bennison and asked a blunt question. “Did you folks come up here to do some hunting?”

Bennison sat down again on the log. He didn’t seem angry any more. “Yeah. We rented the Tyler camp for a week. I was going to do the hunting.”

“Where’s your gun?”

“Back in the camp.”

“Have a gun for her?”

“I told you I was doing the hunting.”

“I was just wondering. I notice she’s got a little bruise under her right eye as if a gun stock had slapped against her face.”

Burt pulled the sweater away from the rounded white right shoulder. There was a purplish bruise there too. He covered the shoulder again.

“She did some target practice with my gun,” Bennison said. “She bruised easily.”

I couldn’t figure what Burt was driving at. He’s never been one to ask useless questions. He’s too lazy. It was obvious to me that the shot had come from a greater distance than a man can aim.

“What’s your business?” Burt asked.

“Well... nothing at the moment. I used to be in the investment business.”

“Married a gal with money, hey?”

“Look here, Stanleyson, I resent this questioning. What’s that got to do with finding out which one of the hunters across the lake shot her?”

“Then she did have money?”

“Suppose she did? We both had money.”

Burt sighed again and turned away from the body. He walked toward the lakeshore and then looked back. A big tree grew close to the rocks along the shore. He squinted up at the tree. Then he ambled down the bank, squatted on a big rock, and stared moodily at the water. Bennison shrugged helplessly and looked at me.

Burt came back up the bank and said, “Let’s go back to the spot where you did this target practicing. Behind the Tyler camp, wasn’t it?”

Bennison stood up, and we all walked back down the lakeshore trail. Once Burt stopped and looked back at the dead woman and said, “Guess there’s no need to move her just yet.”

They had been firing at tin cans propped against a high bank behind the camp. Burt grunted and squatted and picked up a dozen or so of the gleaming brass cartridge cases. He examined them carelessly and stuffed them into his pocket.

Bennison seemed to have gotten tired of trying to figure out what the big man in the wrinkled gray suit was trying to do. He leaned against the cabin and stared out across the lake.

Читать дальше