John MacDonald - The Good Old Stuff

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John MacDonald - The Good Old Stuff» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1982, ISBN: 1982, Издательство: Harper & Row, Жанр: Детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Good Old Stuff

- Автор:

- Издательство:Harper & Row

- Жанр:

- Год:1982

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-06-015038-9

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Good Old Stuff: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Good Old Stuff»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Cinnamon Skin, Free Fall in Crimson

The Empty Copper Sea,

The Good Old Stuff Contemporary MacDonald readers and Travis McGee fans will delight in recognizing these precursors to Travis McGee; and mystery readers who remember them when they first appeared will remark on that extraordinary talent for storytelling, which is as apparent in his early stories as it is in his recent novels.

The Good Old Stuff — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Good Old Stuff», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

In 1950 MacDonald had his first novel published, not in hardcover but as a Fawcett Gold Medal paperback original, and throughout that decade and most of the sixties he continued to write paperbacks so prolifically and well that he forced critics and intelligent readers to take notice of a new book-publishing medium that they might otherwise have dismissed as junk. With the debut of his series character Travis McGee in 1964, MacDonald’s royalties and readership soared even higher, and in due course the author and his hero migrated to hardcover publication and to the best-seller lists.

What’s the secret of his success? The values he admires most in others’ fiction and embodies in his own have been best summarized by MacDonald himself. “First, there has to be a strong sense of story. I want to be intrigued by wondering what is going to happen next. I want the people that I read about to be in difficulties — emotional, moral, spiritual, whatever, and I want to live with them while they’re finding their way out of these difficulties. Second, I want the writer to make me suspend my disbelief... I want to be in some other place and scene of the writer’s devising. Next, I want him to have a bit of magic in his prose style, a bit of unobtrusive poetry. I want to have words and phrases really sing. And I like an attitude of wryness, realism, the sense of inevitability. I think that writing — good writing — should be like listening to music, where you identify the themes, you see what the composer is doing with those themes, and then, just when you think you have him properly identified, and his methods identified, then he will put in a little quirk, a little twist, that will be so unexpected that you read it with a sense of glee, a sense of joy, because of its aptness, even though it may be a very dire and bloody part of the book. So I want story, wit, music, wryness, color, and a sense of reality in what I read, and I try to get it in what I write.”

In these thirteen early tales MacDonald gets what he wants, and so will his millions of fans. This is the good old stuff indeed. Read, and be carried away.

Author’s Foreword

These stories have been selected from hundreds written and published during the five-year period from 1947 to 1952.

This was the process of selection: Martin H. Greenberg of the University of Wisconsin and Francis M. Nevins, Jr., both of them aficionados of the pulp mystery story, wrote me that it would be a useful project to make a collection of the best of the old pulp stories of mine. I was not transfixed with delight. Mildly flattered, yes. But apprehensive about the overall quality of such a collection.

With the invaluable aid of Jean and Walter Shine, they acquired copies of those stories they had not read, and between the four of them, they whittled the list down to thirty. The tear sheets of these stories were obtained from the archives at the University Libraries, the University of Florida in Gainesville, and Sam Gowan, the Assistant Director of Special Resources, sent them along. I had them all turned back into typed manuscript form before looking at them.

I brought the hefty stack of thirty stories up here to the Adirondacks and went through them with care. To my astonishment, I found only three which I felt did not merit republication. The twenty-seven remaining totaled a quarter million words, so I divided them into two lots of approximately equal length. This is the first.

I have made minor changes in all these stories, mostly in the area of changing references which could confuse the reader. Thirty years ago everyone understood the phrase “unless he threw the gun as far as Camera could.” But the Primo is largely forgotten, and I changed him to Superman.

I have updated some of the stories, but only where the plot line was not entangled with and dependent upon the particular era. Those that depend for their effect on the times, the period pieces (“Death Writes the Answer,” “They Let Me Live”), were not updated.

Those stories which could happen at any time, such as “A Time for Dying,” have been updated. I changed a live radio show to a live television show. And in others I changed pay scales, taxi fares, long-distance phoning procedures, beer prices, and so forth to keep from watering down the attention of the reader. This may offend the purists, but my original intention in writing these stories was to entertain. If I did not entertain first the editor and then the readers, I did not get paid. And if I did not get paid, I would have to go find honest work. So the intention is still to entertain, to bemuse, and even to indicate how little changed is our time from that time when these were written.

I was horribly tempted to make other changes, to edit patches of florid prose, substitute the right words for the almost right words, but that would have been cheating, because it would have made me look as if I were a better writer at that time than I was. I was learning the trade.

The fifth and sixth stories in this collection intrigued me because they dealt with the same hero, one Park Falkner, who in some aspects seems like a precursor of Travis McGee. And in other aspects he foreshadows the plots of a lot of bad television series which came along later.

I remember with a particular fondness those editors who gave honest and valuable advice during the early years: Babette Rosmond at Street & Smith; Mike Tilden, Harry Widmer, and Alden Norton at Popular Publications; Bob Lowndes at Columbia Publications.

I remember Mike Tilden saying, “John, for God’s sake stop telling us about people. Stop saying, for example, ‘She was a very clumsy woman.’ Show her falling downstairs and ending up with her head in the fishbowl. Don’t ever say, ‘He was an evil man.’ Show him doing an evil thing.”

I remember Babette Rosmond saying to me, after I had sent her a couple of dozen stories which used my Ordnance and OSS background in the China-Burma-India Theater, “John, now is the time to take off your pith helmet and come home.”

These stories, with the hundreds of others, were written and rewritten at 1109 State Street, Utica, New York; at 8 Jacarandas, Cuernavaca, Morelos, Mexico; at rented houses on Gardenia Street, Clearwater Beach, Florida, and Bruce Avenue three blocks away during the next season; at a rented house on Casey Key, Florida; at Piseco, New York, where I have been editing this collection; and finally at 1430 Point Crisp Road, Sarasota, where we lived for eighteen good years.

I wrote stories in such dogged quantity that often, when I had more than one in a magazine, the second had to be published under a house name: Peter Reed, John Wade Farrell, Scott O’Hara. In this collection, “A Time for Dying” was published under the name of Peter Reed and “Check Out at Dawn” as by Scott O’Hara.

In 1946 I tried to keep at least thirty stories in the mail at all times. When I finished a story, I would make a list of the magazines which might be interested and then send it out again and again until either it was sold or the list was exhausted. There were lots of magazines then. There was an open market for short fiction. There were lots of readers. Bless them!

Assembling this collection was like walking into a room and finding there a lot of old and good friends you had thought dead. The stories are better than I expected them to be, and so in taking the occupational risk of having them published, I hope you will enjoy them as much as they were enjoyed the first time around.

John D. MacDonald

Piseco, New York

June 20, 1982

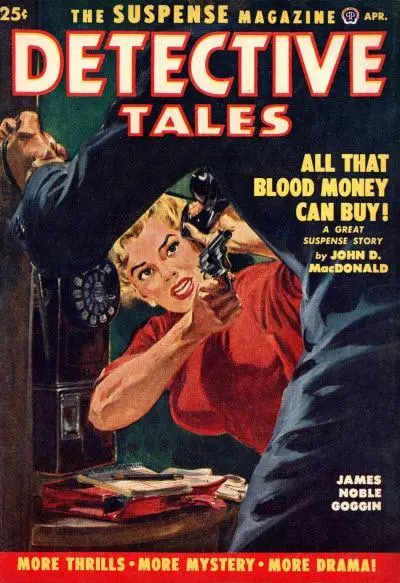

Murder for Money

(aka All That Blood Money Can Buy)

Long ago he had given up trying to estimate what he would find in any house merely by looking at the outside of it. The interior of each house had a special flavor. It was not so much the result of the degree of tidiness, or lack of it, but rather the result of the emotional climate that had permeated the house. Anger, bitterness, despair — all left their subtle stains on even the most immaculate fabrics.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Good Old Stuff»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Good Old Stuff» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Good Old Stuff» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.