The tall young gentleman, holding the brim of his hat with both hands, straight away asked Cratchit: “Would you kindly consider managing Scrooge & Marley on behalf of my family?”

Expressing great surprise — partly because he was surprised, and partly because it was good manners — Cratchit said gratefully, nay, heartily: “It would be an honor and a pleasure.” That evening everyone in the Cratchit family received an extra spoonful of turkey bone soup.

The first action Bob Cratchit took as manager of Scrooge & Marley was to light a good fire in the office and to heap on the coal. His second action was to write a letter to Jonathan Wurdlewart in which he offered an extension of time and a much more equitable interest rate. Three days later Wurdlewart, looking lean and bewildered, showed up at the countinghouse and inquired cautiously of Cratchit: “Have I understood the terms of your letter correctly?”

“I should think you have.”

At which reply Wurdlewart grabbed Cratchit’s hand and nearly shook his arm out of its socket. “Thank you so much, kind sir, from me and my family. Thank you so very, very much.”

Grinning happily, Cratchit replied. “You’re most welcome, I’m sure.”

By the following Christmas the baker was free and clear of his debt, and his shop began to prosper. During that period Bob Cratchit and Jonathan Wurdlewart became friends, and several times their families dined together. But not a word about the evidence, or about Cratchit’s suspicion, passed between them. Nor did Wurdlewart mention that he had followed Scrooge back to his countinghouse that fateful Christmas night with the idea of appealing to him for more time. After standing out in the dreadful cold awhile, however, Wurdlewart saw through the mist someone who looked thin and short as Cratchit approach and enter the establishment of Scrooge & Marley. But Wurdlewart lost his courage, and so he had wandered back home to seek the comfort of his family. It was only after he heard about Scrooge’s death at his desk that he remembered how the old man had viciously belittled Cratchit in front of several people, and Cratchit’s fists had clenched in humiliation. So Wurdlewart came to some conclusions of his own, but he never mentioned what he saw that Christmas night — except to his wife, in whom he confided all things.

One autumn evening, when the Cratchits were visiting the Wurdlewarts, Mrs. Wurdlewart, a robust lady famed for her hot toddies, stirred up a great bowl of spirits and kept ladling it into the men’s cups. Soon the two husbands were red in the face and sentimental in the heart. Expressing the need for some air, they stepped out onto the moonlit cobblestones and took a walk. In a burst of protective feeling for his friend, Cratchit said to Wurdlewart: “You can be sure of one thing, Jonathan, no matter how long I live, I shall never breathe a word of what I know to another living soul.”

Wurdlewart stopped and turned unsteadily toward his friend. “Strange,” he said, “I was about to say very much the same thing to you, Bob.”

At this time they each revealed their suspicions to one another.

“As God is my witness,” said Wurdlewart, “though the thought had passed through my head in a weak moment, I never brought harm to Scrooge. It’s not in my nature.”

“May God strike me dead if I had anything to do with Mr. Scrooge’s demise,” declared Cratchit. “It never once entered my mind.”

In a flash the two friends knew that the other was speaking the truth. Cratchit realized that the rust he had removed from Scrooge’s coat was very likely a marking the old man had acquired when brushing against the rusted lid of the cash box, and Wurdlewart realized that what he had seen that night was probably a configuration of mist, not of man. In the glare of the moon both of their minds continued to wander a few moments: Cratchit thought about Pennerpinch, and Wurdlewart thought about yet another of Scrooge’s debtors whom he had heard threaten the usurer in his office. But in a short time both men dismissed these possibilities as highly improbable, and their minds converged on one idea. At virtually the same moment the two friends had concluded that God, in His infinite wisdom, to satisfy His everlasting desire for justice, and by way of one of His innumerable spiritual agents of mercy, had struck down the old miser.

“God is just,” said Cratchit, thinking that Inspector Grabbe had been correct about Scrooge’s death after all.

“God is good,” said Wurdlewart, thinking that his wife had been correct about Cratchit’s innocence after all.

With an arm around each other’s shoulder, and much more refreshed, the friends swaggered back toward the house to rejoin the festivities.

Postscript

Under Bob Cratchit’s hard-earned experience and thrifty management the establishment of Scrooge & Marley flourished, and within a few years he was able to move his wife and five children out of the mercantile district into a modest yet handsome house (with three fireplaces) far from the sounds of manufacture. Now when the Wurdlewarts appeared at their home, Mrs. Cratchit served crumpets as well as fancy tea, and she became quite a bit more talkative, especially along these lines: “Bob, I’ll be needing a new dress to replace this old rag.” Tiny Tim, who did not die as foreshadowed by the last of the ghostly triumvirate, grew stronger every day and, finally, threw away his crutch altogether. At the same time he was growing smarter. One day he joined the firm as his father’s apprentice. The lad learned quickly, helping to ease the workload on his father considerably. It was not long before Tim was earning a regular wage, and he began expanding the company’s services. In time, the Cratchits were able to buy out Scrooge’s nephew, who was pleased to be finished with such business entirely. The following week a new sign appeared over the door of the counting-house — Cratchit & Son — and Tim, who was no longer so tiny, became shrewder and, with every pound won in commerce, hungrier for more and more profit. And so, as Big Tim observed the following Christmas, “God bless us with another client!”

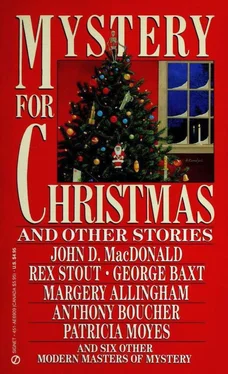

Who Killed Father Christmas?

by Patricia Moyes

“Good morning, Mr. Borrowdale. Nippy out, isn’t it? You’re in early, I see.” Little Miss Mac-Arthur spoke with her usual brisk brightness, which failed to conceal both envy and dislike. She was unpacking a consignment of stout Teddy bears in the stockroom behind the toy department at Barnum and Thrums, the London store. “Smart as ever, Mr. Borrowdale,” she added, jealously.

I laid down my curly-brimmed bowler hat and cane and took off my British warm overcoat. I don’t mind admitting that I do take pains to dress as well as I can, and for some reason it seems to infuriate the Miss MacArthurs of the world.

She prattled on. “Nice looking, these Teddies, don’t you think? Very reasonable, too. Made in Hong Kong, that’ll be why. I think I’ll take one for my sister’s youngest.”

The toy department at Barnum’s has little to recommend it to anyone over the age of twelve, and normally it is tranquil and little populated. However, at Christmastime it briefly becomes the bustling heart of the great shop, and also provides useful vacation jobs for chaps like me who wish to earn some money during the weeks before the university term begins in January. Gone, I fear, are the days when undergraduates were the gilded youth of England. We all have to work our passages these days, and sometimes it means selling toys.

One advantage of the job is that employees — even temporaries like me — are allowed to buy goods at a considerable discount, which helps with the Christmas gift problem. As a matter of fact, I had already decided to buy a Teddy bear for one of my nephews, and I mentioned as much.

Читать дальше