Cesar’s eyes seemed to be smiling independently of his impassive features.

“I don’t know,” he replied after a moment. “You’re the master, my dear. You should know.”

Munoz made one of his vague gestures, as if brushing aside the title Cesar had bestowed on him.

“I insist,” he said slowly, dragging out the words, “on knowing the authorised version.”

Cesar’s lips became infected by the smile that until then had been restricted to his eyes.

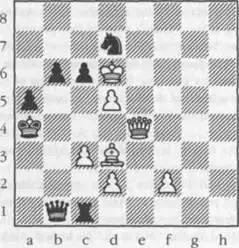

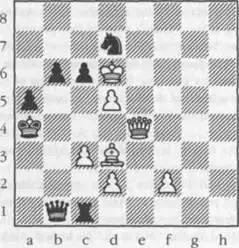

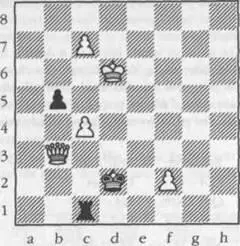

“In that case, I would protect the black king by placing the bishop on c4.” He looked at Munoz with courteous solicitude. “Does that seem right to you?”

“Then I’ll take that bishop,” Munoz said, almost rudely, “with my white bishop on d3. And then you’ll have me in check with your knight on d7.”

“I’ll do no such thing, my friend.” Cesar held his gaze unflinchingly. “I don’t know what you’re talking about. And this is no time to play charades.”

Munoz frowned and looked stubborn.

“You’ll have me in check on d7,” he insisted. “Stop play-acting and concentrate on the board.”

“Why should I?”

“Because you have very few escape routes now. I avoid that check by moving the white king to d6.”

Cesar sighed when he heard this, and his blue eyes rested on Julia. In the dim light, they seemed extraordinarily pale, almost colourless. After placing his cigarette holder between his teeth, he nodded twice, with a slight look of regret on his face.

“Then, I’m sorry to say” – and he did indeed seem put out – “I would have to take the second white knight, the one on b1.” He looked at Munoz contritely. “A pity, don’t you think?”

“Yes. Especially from the knight’s point of view.” Munoz bit his lower lip. “And would you take it with the rook or with the queen?”

“With the queen, naturally.” Cesar seemed offended. “There are certain rules…” He left the phrase hanging in the air with a gesture of his right hand. A fine, pale hand, on the back of which could be seen the bluish ridges of his veins, a hand that Julia now knew was capable of killing, perhaps initiating the lethal blow with the same elegant gesture.

Then, for the first time since they’d arrived, Munoz smiled, that vague, distant smile that never meant anything, that was a response to his strange mathematical reflections rather than to the surrounding reality.

“In your place I would have played queen to c2, but that’s of no importance now,” he said in a low voice. “What I’d like to know is how you were thinking of killing me.”

“Don’t talk nonsense,” replied Cesar, and he seemed genuinely shocked. Then, as if appealing to Munoz’s sense of politeness, he made a gesture in the direction of the sofa where Julia was sitting, though without looking at her. “There’s a young lady present…”

“At this point,” remarked Munoz, the smile still there at one corner of his mouth, “the young lady is, I imagine, as curious as I am. But you didn’t answer my question. Were you thinking of resorting again to the tactic of a blow to the throat or the back of the neck or were you saving a more classical ending for me? I mean poison, a dagger or something like that… How would you put it?” He glanced up at the paintings on the ceiling, seeking some appropriate phrase. “Ah, yes, something ‘Venetian’.”

“I would have said ‘Florentine’,” Cesar corrected him, punctilious as always, although not without a certain admiration. “I had no idea you had a sense of irony about such matters.”

“I don’t,” replied Munoz. “Not at all.” He looked at Julia and pointed at Cesar. “There he is: the man who enjoys the trust of both king and queen. If you want to fictionalise the thing, he’s the plotting bishop, the treacherous Grand Vizier who conspires in the shadows because he is, in fact, the Black Queen in disguise.”

“It would make a marvellous soap opera,” remarked Cesar mockingly, clapping his hands in slow, silent applause. “But you haven’t told me what White would do after losing the knight. Frankly, my dear, I can’t wait to find out.”

“Bishop to d3, check. And Black loses the game.”

“That easy, eh? You frighten me, my friend.”

“Yes, that easy.”

Cesar considered this while he removed what remained of his cigarette from the holder and placed it in an ashtray, having first delicately removed the ash.

“Interesting,” he said and slowly, so as not to alarm Munoz unnecessarily, went over to the English card table next to the sofa. After turning the small silver key in the lock of a chest veneered in lemonwood, he took out the dark, yellowing pieces of a very old ivory chess set that Julia had never seen before.

“Interesting,” he repeated. His slender fingers with their manicured nails arranged the pieces on the board. “The situation, then, would be like this.”

“Exactly,” said Munoz, who was looking at the board from a distance. “The white bishop, when it withdraws from c4 to d3, allows a double check: white queen on black king and the bishop itself on the black queen. The king has no alternative but to flee from a4 to b3 and to abandon the black queen to her fate. The white queen will provide another check on c4, forcing the enemy king to retreat, before the white bishop finishes off the queen.”

“The black rook will take that bishop.”

“Yes, but that’s not important. Without the queen, Black is finished.

What’s more, once that piece disappears from the board the game loses its raison d’etre“

“You may be right.”

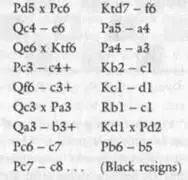

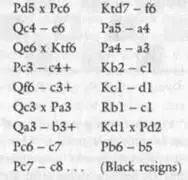

“I am right. The game, or what’s left of it, is decided by the white pawn on d5, which, after taking the black pawn on c6, will advance, with no one to stop it, until it is promoted. That will happen within six or, at most, nine moves.” Munoz put a hand into one of his pockets and drew out a piece of paper covered with pencilled jottings. “These, for example.”

Cesar picked up the piece of paper and very calmly studied the chessboard, his empty cigarette holder clamped between his teeth. His smile was that of a man accepting a defeat that was already written in the stars. One after another he moved the pieces until they represented the final situation: “You’re right. There’s no way out,” he said at last. “Black loses.”

Munoz’s eyes shifted from the board to Cesar.

“Taking the second knight,” he murmured in an objective tone, “was a mistake.”

Cesar shrugged, still smiling.

“After a certain point Black had no choice. You could say that Black was also a prisoner of his mobility, of his natural dynamic. That knight rounded off the game.” For a moment Julia caught in Cesar’s eyes a flash of pride. “In fact, it was almost perfect.”

“Not in chess terms,” said Munoz dryly.

“Chess? My dear friend” – Cesar made a disdainful gesture in the direction of the chess pieces – “I was referring to something more than

a simple chessboard.“ His blue eyes grew dark, as if a hidden world were peering out from beneath their surface. ”I was referring to life itself, to those other sixty-four squares of black nights and white days of which the poet speaks. Or perhaps it’s the other way round, perhaps it should be white nights and black days. It depends on which side of the player we choose to place the image… on where, since we’re talking in symbolic terms, we place the mirror.“

Читать дальше