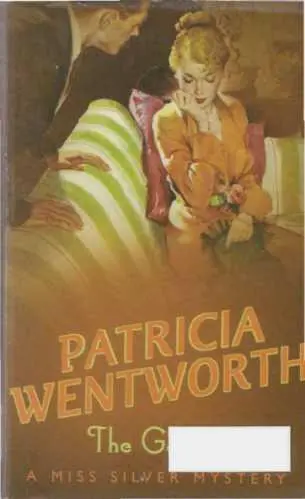

Patricia Wentworth

The Gazebo

also published as The Summerhouse

Miss Silver – #29, 1956

ALTHEA GRAHAM SLIPPED back the catch of the front door. Her mother had recalled her three times already. Perhaps this time she would really get away. But before there was time for her to think that it looked as if it was going to be fine, there was Mrs Graham’s sweet high voice with its note of urgency – ‘Thea! Thea!’

She turned back. Mrs Graham, having surmounted the fatigue of dressing, now sat very comfortably in her own particular armchair with her feet on a cushion and a pale blue spread across her knees. She was a small, frail creature with fair hair, blue eyes, and a complexion upon which she lavished the utmost care. As a girl she had had a good many admirers. Not, perhaps, quite as many as she liked to believe. Their number and the extravagance of their attentions tended to increase when viewed in retrospect, but she had been ‘pretty Winifred Owen’, and when she married Robert Graham the local paper described her as the loveliest of brides.

It was now a good many years since Robert had died leaving her with an income no longer so adequate as it had been, a devoted daughter – she always told everyone how devoted Althea was – and an abiding sense of injury. She hardly remembered him now as a person, but she never forgot the grievance. There was a good deal less money than she had expected. There were death duties, and there was the rising cost of living. These things were somehow Robert’s fault. When the lawyer tried to explain them it only made her head go round. She gazed at him out of limpid blue eyes and said it was all very difficult to understand. And he didn’t mean, he surely couldn’t mean, that the house had been left to Althea and not to her! She couldn’t believe it – she really couldn’t ! A mere child not ten years old – how could Robert do such a thing! And why was it allowed! Surely something could be done about it! It had all been most dreadfully trying.

And it didn’t stop there. Incomes went down and prices continued to go up. Of course there was the house. Houses were worth more than they used to be, and she had almost succeeded in forgetting that The Lodge did not really belong to her.

Althea came a little way into the room and said,

‘What is it, Mother?’

‘Darling, if you will just shut the door – such a draught! Now let me see, what was it? Will you be passing Burrage’s? Because if you were, I thought I might just try that new Sungleam hair-rinse. I thought of it this morning, and then I wasn’t sure, but after all it wouldn’t do any harm just to try it, and then if it didn’t suit me there wouldn’t be any need to go on.’

Time was when Althea would have pointed out that going to Burrage’s would take her at least another twenty minutes, and that she was already late in starting because Mrs Graham had mislaid a pattern of embroidery silk which had had to be looked for, and had then called her back to say that she thought the last apples from Parsons’ were not very good and why not try Harper’s, and – yes, after all, she did think her library book had better be changed.

‘And, darling, why don’t you try some of that Sungleam stuff yourself? They have it in all shades. And really I don’t think you take enough care of your hair. It was such a disappointment to me when it didn’t stay fair – there really isn’t anything like fair hair to set a girl off. But it had a nice gloss, and it used to curl quite naturally. You know, it’s a mistake to let those sort of things go – it really is.’

Althea did not respond. She said briefly, ‘I’ll go to Burrage’s,’ and got herself out of the room.

This time she got herself out of the house too. As she walked down Belview Road she found herself shaking. It was not very often that she had one of those blinding flashes of anger now. She had learned to endure them and not to show what she felt. She had not learned, and would never learn, not to suffer when they came. ‘ It’s a mistake to let those sort of things go – it really is .’ When her mother said that, there had been the lightning stroke of anger and the old searing pain. She had let everything go because she had to let it go. She had let it go because her mother had taken it from her. It wasn’t just her youth and the gloss and curl of her hair. It was freedom, and life, and Nicholas Carey. She had had to let them go because her mother had wept and pleaded, and backed up the weeping and pleading by a series of heart attacks. ‘You can’t leave me, Thea – you can’t ! I’m not asking very much – only that you will stay with me for the short, short time I shall be here. You know, Sir Thomas said it might be a very short time indeed – and Dr Barrington will tell you the same. I don’t ask you not to see Nicholas – I don’t even ask you not to be engaged to him. I only ask you to stay with me for the little, little time I’ve got left.’

All that was five years ago – it was dead. The dead should stay in their graves. They have no business to rise and walk beside you in the face of the day. They are not suitable companions as you go down Belview Road and let the bus catch you up, and do your errands. You must get rid of them before you change the library book, and buy the fish, and match the embroidery silk, and ask the girl at Burrage’s for a packet of Golden Sungleam.

She got on to the bus, and found herself just behind the second Miss Pimm. There were three Miss Pimms, and almost the only time that they were ever seen together was at church. Not because they were not on the most affectionate terms, but to do their shopping and change their books individually gave them more scope. Neither a friend nor a shop assistant can talk or listen to three ladies at once, and all the Miss Pimms were talkers. If there was news to be had they picked it up, if there was news to be given they were forward in imparting it. Althea was hardly in her seat, when Miss Nettie had screwed her head round over her shoulder and was telling her that Sophy Justice had had twins.

‘You remember she married a connexion of ours about five years ago and went out with him to the West Indies – something to do with sugar. Such a pity you couldn’t come to the wedding. Your mother was having one of her attacks, wasn’t she? Sophy really did want you to be a bridesmaid, but in the circumstances of course she couldn’t have counted on it, and the dress wouldn’t have fitted anyone else, but I know she was very sorry. They have three children already, and now these twins – a boy and a girl. Really quite a handful, but her mother tells me they are very much pleased. Of course they never write – just a card at Christmas. And we used to see her going by every day. Such a bush of red hair, but it lighted up well under her veil at the wedding. Dear me, it doesn’t seem as if it could be five years ago!’

For Althea the five years dragged out in retrospect to three times their actual length. The attack which had kept her at her mother’s bedside during the week of Sophy’s wedding had marked the end of her own struggle. However often and however bitterly she looked back, she still couldn’t think what else she could have done. Dr Barrington had been perfectly frank. If Mrs Graham ceased to agitate herself there was every prospect of her recovery. She would have to lead a quiet, regular life, but there was no reason why she should not live to a good old age. If, on the other hand, she was to be subjected to any more scenes, he really could not be answerable for the consequences. There must not, for instance, be another such interview as had precipitated the present attack.

Читать дальше