Laurie R. King

The God of the Hive

The tenth book in the Mary Russell series, 2010

In memory of Noel,

who would have loved Robert Goodman

Friday, 29 August 1924

Two clever London gentlemen. Both wore City suits, both sat in quiet rooms, both thought about luncheon.

The younger was admiring his polished shoes; the older contemplated his stockings, thick with dust.

The one was considering where best to eat; the other was wondering if he was to be fed that day.

One clever man stood, straightening his neck-tie with manicured fingers. He reached out to give the silver pen a minuscule adjustment, returning it to symmetry with the edge of the desk, then walked across the silken carpet to the door. There he surveyed the mirror that hung on the wall, leaning forward to touch the white streak-really quite handsome-over the right temple before settling his freshly brushed hat over it. He firmed the tie again, and reached for the handle.

The other man, too, tugged at his tie, grateful for it. The men who had locked him here had taken his shoes and belt, but left him his neck-tie. He could not decide if they-or, rather, the mind in back of them -had judged the fabric inadequate for the suicide of a man his size, or if they had wished subtly to undermine his mental state: The length of aged striped silk was all that kept his suit trousers from tumbling around his ankles when he stood. There was sufficient discomfort in being hungry, cold, unshaven, and having a lidded bucket for toilet facilities without adding the comic indignity of drooping trousers.

Twenty minutes later, the younger man was reviewing his casual exchange with two high-ranking officials and a newspaper baron-the true reason for his choice of restaurant-while his blue eyes dutifully surveyed the print on a leather-bound menu; the other man’s pale grey gaze was fixed on a simple mathematical equation he’d begun to scratch into the brick wall with a tiny nail he’d uncovered in a corner:

a ÷ (b+c+d)

Both men, truth to tell, were pleased with their progress.

Saturday, 30 August-

Tuesday, 2 September

1924

A child is a burden, after a mile.

After two miles in the cold sea air, stumbling through the night up the side of a hill and down again, becoming all too aware of previously unnoticed burns and bruises, and having already put on eight miles that night-half of it carrying a man on a stretcher-even a small, drowsy three-and-a-half-year-old becomes a strain.

At three miles, aching all over, wincing at the crunch of gravel underfoot, spine tingling with the certain knowledge of a madman’s stealthy pursuit, a loud snort broke the silence, so close I could feel it. My nerves screamed as I struggled to draw the revolver without dropping the child.

Then the meaning of the snort penetrated the adrenaline blasting my nerves: A mad killer was not about to make that wet noise before attacking.

I went still. Over my pounding heart came a lesser version of the sound; the rush of relief made me stumble forward to drop my armful atop the low stone wall, just visible in the creeping dawn. The cow jerked back, then ambled towards us in curiosity until the child was patting its sloppy nose. I bent my head over her, letting reaction ebb.

Estelle Adler was the lovely, bright, half-Chinese child of my husband’s long-lost son: Sherlock Holmes’ granddaughter. I had made her acquaintance little more than two hours before, and known of her existence for less than three weeks, but if the maniac who had tried to sacrifice her father-and who had apparently intended to take the child for his own-had appeared from the night, I would not hesitate to give my life for hers.

She had been drugged by said maniac the night before, which no doubt contributed to her drowsiness, but now she studied the cow with an almost academic curiosity, leaning against my arms to examine its white-splashed nose. Which meant that the light was growing too strong to linger. I settled the straps of my rucksack, lumpy with her possessions, and reached to collect this precious and troublesome burden.

“Are you-” she began, in full voice.

“Shh!” I interrupted. “We need to whisper, Estelle.”

“Are you tired?” she tried again, in a voice that, although far from a whisper, at least was not as carrying.

“My arms are,” I breathed in her ear, “but I’m fine.”

“I could ride pickaback,” she said.

“Are you sure?”

“I do with Papa.”

Well, if she could cling to the back of that tall young man, she could probably hang on to me. I shifted the rucksack around and let her climb onto my back, her little hands gripping my collar. I bent, tucking my arms under her legs, and set off again.

Much better.

It was a good thing Estelle knew what to do, because I was probably the most incompetent nurse-maid ever to be put in charge of a child. I knew precisely nothing about children; the only one I had been around for any length of time was an Indian street urchin three times this one’s age and with more maturity than many English adults. I had much to learn about small children. Such as the ability to ride pickaback, and the inability to whisper.

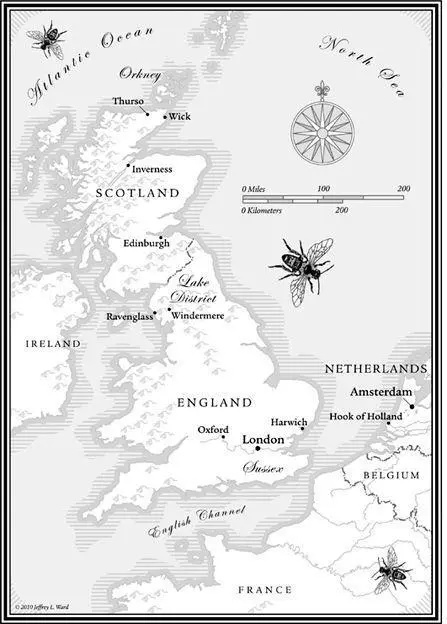

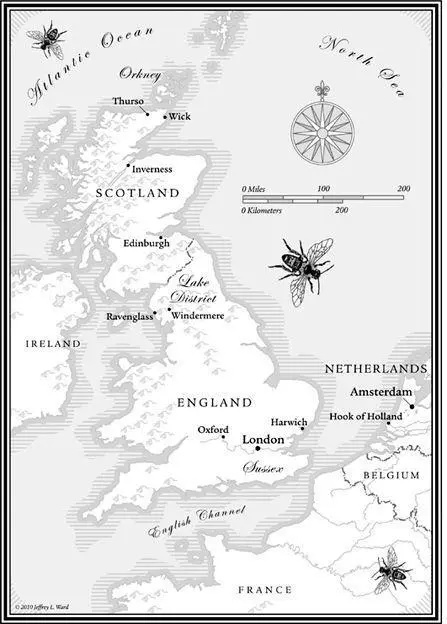

The child’s suggestion allowed me to move faster down the rutted track. We were in the Orkneys, a scatter of islands past the north of Scotland, coming down from the hill that divided the main island’s two parts. Every step took us farther away from my husband; from Estelle’s father, Damian; and from the bloody, fire-stained prehistoric altar-stone where Thomas Brothers had nearly killed both of them.

Why not bring in the police, one might ask. They can be useful, and after all, Brothers had killed at least three others. However, things were complicated-not that complicated wasn’t a frequent state of affairs in the vicinity of Sherlock Holmes, but in this case the complication took the form of warrants posted for my husband, his son, and me. Estelle was the only family member not being actively hunted by Scotland Yard.

Including, apparently and incredibly, Holmes’ brother. For forty-odd years, Mycroft Holmes had strolled each morning to a grey office in Whitehall and settled in to a grey job of accounting-even his longtime personal secretary was a grey man, an ageless, sexless individual with the leaking-balloon name of Sosa. Prime Ministers came and went, Victoria gave way to Edward and Edward to George, budgets were slashed and expanded, wars were fought, decades of bureaucrats flourished and died, while Mycroft walked each morning to his office and settled to his account books.

Except that Mycroft’s grey job was that of é minence grise of the British Empire. He inhabited the shadowy world of Intelligence, but he belonged neither to the domestic Secret Service nor to the international Secret Intelligence Service. Instead, he had shaped his own department within the walls of Treasury, one that ran parallel to both the domestic branch and the SIS. After forty years, his power was formidable.

If I stopped to think about it, such unchecked authority in one individual’s hands would scare me witless, even though I had made use of it more than once. But if Mycroft Holmes was occasionally cold and always enigmatic, he was also sea-green incorruptible, the fixed point in my universe, the ultimate source of assistance, shelter, information, and knowledge.

Читать дальше