"Do you mind being a little more explicit?" said Hugh. "What is it you think you know?"

"I believe Wally and Harold White had some scheme on hand for making money. He said something to me - oh, more than once! - about making his fortune, all through White. As a matter of fact, it was when I rather went for him about lending money to White. He had lent him money, you know, Aunt Ermy, and I told him he'd no right to. And then he said that about making his fortune, and White putting him on to a good thing. I didn't pay much heed at the time, but now I can't help wondering. It would be so like him!"

"I'm afraid I haven't grasped the gist of this, Mary," said Hugh. "What's the connection between this, and Baker?"

"Wally knew Aunty Ermy wouldn't give him money to invest in any scheme of Harold White's making. Then Aunt Ermy found out about Gladys Baker. Do you think - do you think he could possibly have made up that story of being blackmailed for five hundred, to get money for whatever scheme it was White had put up to him?"

Hugh, who had listened in blank amazement, said: "Frankly, no, I don't. Good Lord, Mary, think it over for yourself! It's preposterous! Dash it, it's indecent!"

"She's very likely right!" said Ermyntrude, in tones of swelling indignation. "That would just be Wally all over! Oh, I see it now! The idea of it! Getting money out of me to save a scandal, as he knew very well he would, and then blueing the lot on some rubbishy plan of White's!"

"Do you mean to tell me you seriously believe that to get money for an investment, he would have told you he was being blackmailed by the brother of a girl he'd seduced?" said Hugh. "Look here, Mrs. Carter, surely that's too steep!"

"Oh no, it isn't! I can see him doing it!" said Ermyntrude. "There never was such a man for turning things to good account. Oh, it fairly makes my blood boil!"

"I - I should think it might," said Hugh, awed.

Hugh, although he was becoming inured to the vagaries of Ermyntrude and her daughter, was not prepared to find them accepting Mary's theory with enthusiasm. But, within five minutes of her having explained it to them, nothing could have shaken their belief in its truth. Ermyntrude, indeed, seemed to feel that such duplicity on Wally's part was unpardonable; but Vicky accorded it her frank admiration.

"It's rather sad, really, the way one never appreciates a person till he's dead," she said. "Oh, I do think it was truly adroit of him, don't you, Ermyntrude darling? Do you suppose it had anything to do with his being murdered?"

"Even if it were true, why should it have?" asked Hugh.

"Oh, I don't know, but I wouldn't be at all surprised if we discovered it was all part of some colossal plot, and wholly tortuous and incredible."

"Then the sooner you get rid of that idea the better!"

She looked at him through the sweep of her lashes. "Fusty!" she said gently.

Hugh was annoyed. "I'm not in the least fusty, but.."

"And dusty, and rolled up with those disgusting mothballs."

"Ducky, don't be rude!" said Ermyntrude, quite shocked.

"Well, he reminds me of greenfly, and blight, and frost in May, and old clothes, and '

"Anything else?" inquired Hugh, with an edge to his voice.

"Yes, lots of things. Cabbages, and fire-extinguishers, and-'

"Would you by any chance like to know what you remind me of?" said Hugh, descending ignobly to a to quoque! form of argument.

"No, thank you," said Vicky sweetly.

Hugh could not help grinning at this simple method of spiking his guns, but Ermyntrude, who thought him a very nice young man, was for once almost cross with her daughter, and commanded her to remember her manners. "One thing's certain," she said, reverting to the original topic of discussion, "I shall ask that Harold White just what he wanted with Wally yesterday!"

"Yes, but ought I to say anything to the Inspector?" said Mary.

"I don't think I would," said Hugh. "Unless, of course, you find that your theory is correct. Frankly, I doubt whether he'd believe such a tale."

"No, I don't think he would," agreed Vicky. "He's got a petrified kind of mind which reminds me frightfully of someone, only I can't remember who it is, for the moment."

"Me," said Hugh cheerfully.

"Oh, I wouldn't be at all surprised if you're right!" said Vicky.

"I'm ashamed of you, Vicky!" said Ermyntrude.

Mary echoed this statement a few minutes later, when she accompanied Hugh to his car, but he only laughed and said he rather enjoyed Vicky's antics.

"You don't have to live with her," said Mary.

"No, I admit it's tough on you. Seriously, Mary, do you believe that your extraordinary cousin really did make up that blackmailing story?"

"It's a dreadful thing to say, but I can't help seeing that it would be just like him," replied Mary.

Harold White, to whom Janet faithfully delivered Ermyntrude's message, walked over to Palings after dinner. The party he disturbed was not an entirely happy one, for the Prince, who did not believe in letting grass grow under his feet, had been interrupted at the beginning of a promising tete-a-tete with his hostess, by the entrance into the room of Vicky and Mary. This naturally put an end to his projected tender passages, and he was annoyed when he discovered that neither lady seemed to have the least intention of leaving him alone with Ermyntrude. Mary sat down with a tea-cloth which she was embroidering, an occupation, which, however meritorious in itself, the Prince found depressing; and Vicky (in a demure black taffeta frock with puff sleeves) chose to enact the role of innocent little daughter, sinking down on to a floor cushion at her mother's feet, and leaning her head confidingly against Ermyntrude's knees. As she had previously told Mary that she thought it was time she awoke the mothercomplex in Ermyntrude, Mary had no difficulty in recognising the tactics underlying this touching pose. The Prince, of course, could not be expected to realise that this display of daughterly affection was part of a plot to undo him, but he very soon became aware of a change in an atmosphere which had been extremely propitious. He made the best of it, for it was part of his stock-in-trade to adapt himself gracefully to existing conditions, but Mary surprised a very unamiable look on his face when she happened to glance up once, and saw him watching Vicky.

When Harold White came in, maternal love gave place to palpable hostility. Ermyntrude cut short his speech of condolence, by saying: "I'm sure it's very kind of you to spare the time to come and see me, Mr. White. I hope it wasn't asking too much of you!"

"Oh, not a bit of it! Only too glad!" responded White, drawing up a chair. "Poor old Wally! Dreadful business, isn't it? The house doesn't seem the same without him."

"I dare say it doesn't," said Ermyntrude. "But what I want to know, Mr. White, is what Wally was doing at your place yesterday."

He looked slightly taken aback. "Doing there? What do you mean? He wasn't doing anything."

"What did he go for?" demanded Ermyntrude.

"Look here, Mrs. Carter, I asked poor old Wally to come over and have tea, if he'd nothing better to do, and that's all there was to it."

"Well, I've got a strong notion it wasn't all," said Ermyntrude. "What's more, I'd like to know what that Jones person had got to do with it."

"Really, if I can't invite a couple of friends to tea without being asked why—'

"That's not so, Mr. White, and heaven forbid I should go prying into what doesn't concern me, but it seems a funny thing to me that you should be so anxious to get Wally over to your place - which you won't deny you were, ringing him up no less than three times - if it was only to see him drink a cup of tea. Besides, he was murdered."

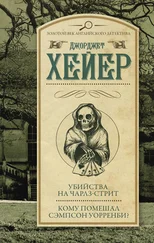

Читать дальше