As she sat by the fire in her own flat, the retreat and refuge she'd imagined in those dreams, she thought about other places where she had laid her head. There was the room in Lambeth-why had she lived there at all? She came from Girton, straight to London to interview with Maurice. Then when he'd sent word that the job was hers, she found lodgings in the only area she could afford and knew at all, the place where she'd grown up: Lambeth. Her room was clean, tidy, and there was a meal in the evening when she arrived home, but she walked through the slums each day, through streets of depression and want. She had realized, even then, that her choice to live in a place so compromised, among people so wretched, was due to the fact that she was still numb. Living in such troubled quarters was tantamount to touching her skin with a hot needle-it reminded her that she was still alive, that she was not dead, that the war might have taken so much, but it had not taken her life.

It was later, after Maurice retired and she set up her business on her own, that at the behest of Lady Rowan she came back to live at the Comptons' Ebury Place mansion. Her rooms were more than comfortable and clean, they were light and cozy, and her every need was catered for-yet she had still not found her place, had never quite felt at home. She was neither this nor that, not one class or the other. Now, as she reflected upon her journey and the years past, she realized she had come this far and had no idea what might come next, or what there might be for her to aspire to. She understood that she knew only how to climb mountains; having reached a certain place of elevation, she was unaccustomed to the view of the road already taken, and where her next steps might lead. Losing the document case had been akin to losing a suitcase of clothes on a very long journey. She knew neither the next destination, nor how she might prepare to travel.

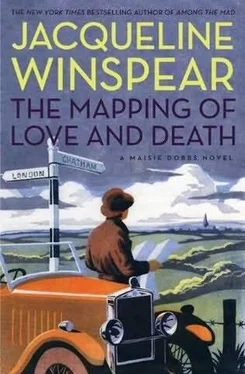

The following day, after a brief meeting with Billy at their office in Fitzroy Square, Maisie embarked upon the drive down to Chatham, where the army's cartographers were trained at the School of Military Engineering. As Davidson predicted, Maisie's telephone call to the school was shunted along to Major Ian Temple, who had been described to her by the young man who answered the telephone as "the one who looks after outside people, and that sort of thing." She suspected it was not a welcome task, but one delegated to an officer who seemed to have time on his hands.

A long journey in her motor car, a two-seater MG 14/40, always gave Maisie an opportunity to engage in uninterrupted thought. There was something about the rhythm of the road, the tires against tarmacadam that allowed her to delve deeply into whatever challenge was engaging her attention. She would change gears, slow down, speed up, as the journey required, and at no point was she anything but attentive to the task of driving, but at the same time, it was as if in the act of travel, her immediate concerns were lulled, and in her contemplation she seemed to plumb a greater depth of understanding.

She had put a folder and some index cards into a plain carrier bag with string handles, instead of her document case, and she found that once again the loss of her case took on a deeper meaning during the course of her day. Each morning she donned clothing suited to her work, sensible garb that suggested she should be taken seriously as a professional woman with her own business. She dressed as if she were putting on a suit of armor for battle, and when she finally picked up the document case as she left the flat, it became as important to her as a scabbard might be to a warrior. Now, on the passenger seat, her belongings were held in a bag of paper and string. The significance of such a development occupied her for most of the journey.

The School of Military Engineering was another forces establishment in a town that was also home to the Chatham Dockyard, and as she made her way to Brompton Barracks, where Major Ian Temple had agreed to meet her at noon, she thought of the thousands of young men across the centuries who had come to the town in service of their country. What might Michael Clifton have thought of this place? He came from an historic part of America, a city that had no form in Maisie's imagination because she could not comprehend a country of such expanse and difference; but growing up in such an environment, he must have developed a keen respect for the past and, as a cartographer, a sharper sense of the events and experiences that frame a place and define its people. How would he have felt as he made his way up to the barracks? Chatham had been the focus of military operations since the Middle Ages, and had earned its reputation as a naval base in the Napoleonic Wars. What might his first impressions have been, and how might he have made friends? Had he been teased about his accent by his fellow men? Or had they looked up to him, curious as to why he had enlisted in a war that was not of his country's making? More than anything, she hoped she could find someone who might remember him.

Maisie parked and, before leaving the motor car, placed several index cards in her shoulder bag. She set off towards the main entrance to a series of boxlike buildings built in the early 1800s, and was surprised to be greeted at the door by Major Temple, a man of distinct military bearing but with an approachability that had eluded Peter Whitting. Temple led Maisie along a corridor where white walls were half paneled with English oak, towards a wooden staircase, where they made their way up to the first floor. It seemed that nothing was out of place in Temple's office. Equipment similar to that which she had seen at Whitting's house was positioned on a series of shelves alongside the door, and behind the desk more shelves held books on military strategy.

Temple was businesslike in his approach, and had made an effort to accommodate Maisie's inquiry. "I'm sorry I didn't have much time when you telephoned, Miss Dobbs; however, I have managed to locate some information on Michael Clifton. Of course, you understand that your request is somewhat out of the ordinary. We are not used to the bereaved contacting us, especially via a third party."

"Yes, I do understand; yet by the same token, the circumstances of Lieutenant Clifton's enlistment and service are unusual-he was an American citizen, so I would have thought he might have been turned down for service."

Temple shrugged and leaned back in his chair. "I wish it were as simple as that, Miss Dobbs. It's so easy, after the event, to look at what procedure should have been employed, but in a time of war people do what they feel is right to get the job done." He picked up a folder on his desk and untied a short length of twine securing the pages inside. "I have here Clifton's enlistment details, and the notes of the officer on duty at the time. Clifton had evidence of an impressive background in a field in which we had to improve-that of cartography. He had an engineer's university education and had worked as both a surveyor and a cartographer, and he was familiar with developments in measuring the land. He was young, clever, and inquisitive, and we were trying to get new tools and practices out into the field, using sound and aerial photography. In short, he was exactly the sort of chap we were hoping to recruit. Clifton was just what we wanted."

"Major Temple, you sound as if you knew him personally."

Temple shook his head and looked down at his notes. "No, I didn't. I was an artilleryman in the war. But I know what our priorities were, and I know that Michael Clifton would not have been turned away. The fact that his father was a British citizen was in his favor-if the infantry were turning a blind eye to age in a bid to recruit, then we could let a matter of citizenship go through without comment."

Читать дальше