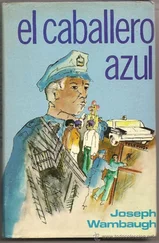

Joseph Wambaugh - The Blue Knight

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Joseph Wambaugh - The Blue Knight» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Blue Knight

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Blue Knight: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Blue Knight»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Blue Knight — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Blue Knight», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

He probably had only a few months’ experience. They stick these deputy D.A.’s in the preliminary hearings to give them instant courtroom experience handling several cases a day, and I figured this one hadn’t been here more than a couple months. I’d never seen him before and I spent lots of time in court because I made so many felony pinches.

“Where’s the other witness?” asked the D.A., and for the first time I looked around the courtroom and spotted Homer Downey, who I’d almost forgotten was subpoenaed in this case. I didn’t bother talking with him to make sure he knew what he’d be called on to testify to, because his part in it was so insignificant you almost didn’t need him at all, except as probable cause for me going in the hotel room on an arrest warrant.

“Let’s see,” muttered the D.A. after he’d talked to Downey for a few minutes. He sat down at the counsel table reading the complaint and running his long fingers through his mop of brown hair. The public defender looked like a well-trimmed ivy-leaguer, and the D.A., who’s theoretically the law and order guy, was mod. He even wore round granny glasses.

“Downey’s the hotel manager?”

“Right,” I said as the D.A. read my arrest report.

“On January thirty-first, you went to the Orchid Hotel at eight-two-seven East Sixth Street as part of your routine duties?”

“Right. I was making a check of the lobby to roust any winos that might’ve been hanging around. There were two sleeping it off in the lobby and I woke them up intending to book them when all of a sudden one of them runs up the stairs, and I suddenly felt I had more than a plain drunk so I ordered the other one to stay put and I chased the first one. He turned down the hall to the right on the third floor and I heard a door close and was almost positive he ran into room three-nineteen.”

“Could you say if the man you chased was the defendant?”

“Couldn’t say. He was tall and wore dark clothes. That fleabag joint is dark even in the daytime, and he was always one landing ahead of me.”

“So what did you do?”

“I came back down the stairs, and found the first guy gone. I went to the manager, Homer Downey, and asked him who was living in room three-nineteen, and he showed me the name Timothy Landry on the register, and I used the pay telephone in the lobby and ran a warrant check through R and I and came up with a fifty-two-dollar traffic warrant for Timothy Landry, eight-twenty-seven East Sixth Street. Then I asked the manager for his key in case Landry wouldn’t open up and I went up to three-nineteen to serve the warrant on him.”

“At this time you thought the guy that ran in the room was Landry?”

“Sure,” I said, serious as hell.

I congratulated myself as the D.A. continued going over the complaint because that wasn’t a bad story now that I went back over it again. I mean I felt I could’ve done better, but it wasn’t bad. The truth was that a half hour before I went in Landry’s room I’d promised Knobby Booker twenty bucks if he turned something good for me, and he told me he tricked with a whore the night before in the Orchid Hotel and that he knew her pretty good and she told him she just laid a guy across the hall and had seen a gun under his pillow while he was pouring her the pork.

With that information I’d gone in the hotel through the empty lobby to the manager’s room and looked at his register, after which I’d gotten the passkey and gone straight to Landry’s room where I went in and caught him with the gun and the pot. But there was no way I could tell the truth and accomplish two things: protecting Knobby, and convicting a no-good dangerous scumbag that should be back in the joint. I thought my story was very good.

“Okay, so then you knew there was a guy living in the room and he had a traffic warrant out for his arrest, and you had reason to believe he ran from you and was in fact hiding in his room?”

“Correct. So I took the passkey and went to the room and knocked twice and said, ‘Police officer.’”

“You got a response?”

“Just like it says in my arrest report, counsel. A male voice said, ‘What is it?’ and I said, ‘Police officer, are you Timothy Landry?’ He said, ‘Yeah, what do you want?’ and I said, ‘Open the door, I have a warrant for your arrest.’”

“Did you tell him what the warrant was for?”

“Right, I said a traffic warrant.”

“What did he do?”

“Nothing. I heard the window open and knew there was a fire escape on that side of the building, and figuring he was going to escape, I used the passkey and opened the door.”

“Where was he?”

“Sitting on the bed by the window, his hand under the mattress. I could see what appeared to be a blue steel gun barrel protruding a half inch from the mattress near his hand, and I drew my gun and made him stand up where I could see from the doorway that it was a gun. I handcuffed the defendant and at this time informed him he was under arrest. Then in plain view on the dresser I saw the waxed-paper sandwich bag with the pot in it. A few minutes later, Homer Downey came up the stairs, and joined me in the defendant’s room and that was it.”

“Beautiful probable cause,” the D.A. smiled. “And real lucky police work.”

“Real luck,” I nodded seriously. “Fifty percent of good police work is just that, good luck.”

“We shouldn’t have a damn bit of trouble with Chimel or any other search and seizure cases. The contraband narcotics was in plain view, the gun was in plain view, and you got in the room legally attempting to serve a warrant. You announced your presence and demanded admittance. No problem with eight-forty-four of the penal code.”

“Right.”

“You only entered when you felt the man whom you held a warrant for was escaping?”

“I didn’t hold the warrant,” I reminded him. “I only knew about the existence of the warrant.”

“Same thing. Afterwards, this guy jumped bail and was rearrested recently?”

“Right.”

“Dead bang case.”

“Right.”

After the public defender was finished talking with Landry he surprised me by going to the rear of the courtroom and reading my arrest report and talking with Homer Downey, a twitchy little chipmunk who’d been manager of the Orchid for quite a few years. I’d spoken to Homer on maybe a half-dozen occasions, usually like in this case, to look at the register or to get the passkey.

After what seemed like an unreasonably long time, I leaned over to the D.A. sitting next to me at the counsel table. “Hey, I thought Homer was the people’s witness. He’s grinning at the P.D. like he’s a witness for the defense.”

“Don’t worry about it,” said the D.A. “Let him have his fun. That public defender’s been doing this job for exactly two months. He’s an eager beaver.”

“How long you been going it?”

“Four months,” said the D.A., stroking his moustache, and we both laughed.

The P.D. came back to the counsel table and sat with Landry, who was dressed in an open-throat, big-collared, brown silk shirt, and tight chocolate pants. Then I saw an old skunk come in the courtroom. She had hair dyed like his, and baggy pantyhose and a short skirt that looked ridiculous on a woman her age, and I would’ve bet she was one of his girlfriends, maybe even the one he jumped bail on, who was ready to forgive. I was sure she was his baby when he turned around and her painted old kisser wrinkled in a smile. Landry looked straight ahead, and the bailiff in the court was not as relaxed as he usually was with an in-custody felony prisoner sitting at the counsel table. He too figured Landry for a bad son of a bitch, you could tell.

Landry smoothed his hair back twice and then seldom moved for the rest of the hearing.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Blue Knight»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Blue Knight» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Blue Knight» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.