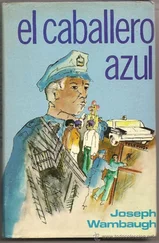

Joseph Wambaugh - The Blue Knight

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Joseph Wambaugh - The Blue Knight» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Blue Knight

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Blue Knight: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Blue Knight»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Blue Knight — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Blue Knight», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Aaron kept talking about the ‘laundry,’ and at first I didn’t get it even though I knew that Red was getting ready to move one of his back offices. And even though I never saw it, or any other back office, I knew about them from talking to bookie agents and people in the business. Aaron was worrying about the door to the laundry and I figured there was something about the office door being too close to the laundry door, and Aaron tried to argue Red into putting another door in the back near an alley, but Red thought it would be too suspicious.

“That was all I heard, and then one day, when Red was taking me to his club for dinner, he said he had to stop by to pick up some cleaning and he parks by this place near Sixth and Kenmore, and he goes in a side door and comes out after a few minutes and says his suits weren’t ready. Then I noticed the sign on the window. It was a Chinese laundry.” Reba took two huge drags, blowing one through her nose as she drew on the second one.

“You’re a smart girl, Reba,” said Charlie.

“I ain’t guaranteeing this is the right laundry, Mister Bronski. In fact, I ain’t even sure the laundry they were talking about had anything to do with the back office. I just think it did.”

“I think you’re right,” said Charlie.

“You got to protect me, Mister Bronski. I got to live with him, and if he knows, I’ll die. I’ll die in a bad way, a real bad way, Mister Bronski. He told me once what he did to a girl that finked on him. It was thirty years ago, and he talked about it like it was yesterday, how she screamed and screamed. It was so awful it made me cry. You got to protect me!”

“I will, Reba. I promise. Do you know the address of the laundry?”

“I know,” she nodded. “There were some offices or something on the second floor, maybe like some business offices, and there was a third floor but nothing on the windows in the third floor.”

“Good girl, Reba,” Charlie said, taking out his pad and pencil for the first time, now that he didn’t have to worry about his writing breaking the flow of the interrogation.

“Charlie, give me your keys,” I said. “I better get back on patrol.”

“Okay, Bumper, glad you could come.” Charlie nipped me the keys. “Leave them under the visor. You know where we park?”

“Yeah, I’ll see you later.”

“I’ll let you know what happens, Bumper.”

“See you, Charlie. So long, kid,” I said to Reba.

“Bye,” she said, wiggling her fingers at me like a little girl.

ELEVEN

IT WAS OKAY driving back to the Glass House in the vice car because of the air conditioning. Some of the new black-and-whites had it, but I hadn’t seen any yet. I turned on the radio and switched to a quiet music station and lit a cigar. I saw the temperature on the sign at a bank and it said eighty-two degrees. It felt hotter than that. It seemed awfully muggy.

After I crossed the Harbor Freeway I passed a large real estate office and smiled as I remembered how I cleaned them out of business machines one time. I had a snitch tell me that someone in the office bought several office machines from some burglar, but the snitch didn’t know who bought them or even who the burglar was. I strolled in the office one day during their lunch hour when almost everyone was out and told them I was making security checks for a burglary prevention program the police department was sponsoring. A cute little office girl with a snappy fanny took me all around the place and I checked their doors and windows and she helped me write down the serial number of every machine in the place so that the police department would have a record if they were ever stolen. Then as soon as I got back to the station, I phoned Sacramento and gave them the numbers and found that thirteen of the nineteen machines had been stolen in various burglaries around the greater Los Angeles area. I went back with the burglary dicks and impounded them along with the office manager. IBM electric typewriters are just about the hottest thing going right now. Most of the machines are sold by the thieves to “legitimate” businessmen who, like everyone else, can’t pass up a good buy.

It was getting close to lunch time and I parked the vice car at the police building and picked up my black-and-white, trying to decide where to have lunch. Olvera Street was out, because I’d had Mexican food with Cruz and Socorro last night. I thought about Chinatown, but I’d been there Tuesday, and I was just about ready to go to a good hamburger joint I know of when I thought about Odell Bacon. I hadn’t had any bar-b-que for a while, so I headed south on Central Avenue to the Newton Street area and the more I thought about some bar-b-que the better it sounded and I started salivating.

I saw a Negro woman get off a bus and walk down a residential block from Central Avenue and I turned on that street for no reason, to get over to Avalon. Then I saw a black guy on the porch of a whitewashed frame house. He was watching the woman and almost got up from where he was sitting until he saw the black-and-white. Then he pretended to be looking at the sky and sat back, a little too cool, and I passed by and made a casual turn at the next block and then stomped down and gave her hell until I got to the first street north. Then I turned east again, south on Central, and finally made the whole block, deciding to come up the same street again. It was an old scam around here for purse snatchers to find a house where no one was home and sit on the stoop of the house near a bus stop, like they lived at the pad, and when a broad walked by, to run out, grab the purse, and then cut through the yard to the next street where a car would be stashed. Most black women around here don’t carry purses. They carry their money in their bras out of necessity, so you don’t see that scam used too much anymore, but I would’ve bet this guy was using it now. And this woman had a big brown leather purse. You just don’t get suspicious of a guy when he approaches you from the porch of a house in your own neighborhood.

I saw the woman in mid-block and I saw the guy walking behind her pretty fast, I got overanxious and pushed a little too hard on the accelerator, instead of gliding along the curb, and the guy turned around, saw me, and cut to his right through some houses. I knew there’d be no sense going after him. He hadn’t done anything yet, and besides, he’d lay up in some backyard like these guys always do and I’d never find him. I just went on to Odell Bacon’s Bar-b-que, and when I passed the woman I glanced over and smiled, and she smiled back at me, a pleasant-looking old ewe. There were white sheep and black sheep and there were wild dogs and a few Pretty Good Shepherds. There’d be one sheep herder less after tomorrow, I thought.

I could smell the smoky meat a hundred yards away. They cooked it in three huge old-fashioned brick ovens. Odell and his brother Nate were both behind the counter when I walked in. They wore sparkling white cook’s uniforms and hats and aprons even though they served the counter and watched the register and didn’t have to do the cooking anymore. The place hadn’t started to fill up for lunch yet. Only a few white people ate there, because they’re afraid to come down here into what is considered the ghetto, and right now there were only a couple customers in the place and I was the only paddy. Everyone in South L.A. knew about Bacon’s bar-b-que though. It was the best soul food and bar-b-que restaurant in town.

“Hey, Bumper,” said Nate, spotting me first. “What’s happening man?” He was the youngest, about forty, coffee brown. He had well-muscled arms from working construction for years before he came in as Odell’s partner.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Blue Knight»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Blue Knight» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Blue Knight» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.