‘We’d better be going.’

‘I hope you’ll come to the repatriation ceremony. It’ll be something else, I promise you.’

‘I’d like to come. Thank you.’

‘Bye Ruth,’ Bob stands aside. ‘Bye Kate.’

As they go out of the room, Ruth sees the case containing the grass snake, its glass eyes winking in the afternoon sunlight.

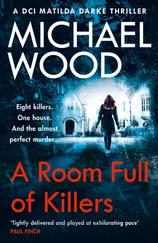

Up next is Judy. She hasn’t brought flowers or grapes. Instead she dumps a couple of lurid-looking paperbacks on his locker.

‘Thought you might want something to read.’

Nelson isn’t much of a reader. One of the books has a skull on the cover, the other a swastika. He squints at the blurbs: conspiracy… war… torture… blackmail… death. Judy really has him down as the sensitive type, doesn’t she?

‘I heard all about last night,’ he says.

‘Who from? Oh, Clough’s been in has he? What did he tell you?’

‘Just that you solved Operation Octopus.’

Judy seems to relax slightly. ‘It was a lucky guess. A series of lucky guesses.’

‘Sounded like good police work to me.’

Judy looks away. ‘I messed up. Clough had to save me.’

‘He saved me once,’ says Nelson. ‘Don’t worry about it.’

‘I should never have gone there without back-up but I wanted to solve it on my own.’

‘Policing’s about teamwork,’ says Nelson, who has never waited for back-up in his life.

‘You’re right,’ says Judy, fiddling with a hand sanitiser. ‘Clough’s a better team player than me.’

‘I hear he wrestled a mad horse to the ground.’

Judy laughs. ‘He was scared stiff. Did he tell you that? Mind you, it was terrifying, shut in a small space with a horse like that. I like horses but I’m not sure I ever want to see one again.’

‘So you’re not going to go back and see Randolph Smith?’

‘Did Clough tell you I fancied him? I don’t. He was brilliant last night though. I don’t know what would have happened if he hadn’t turned up when he did.’

‘So the older sister turned out to be the black sheep?’

‘Yes. She was the clever one, despised the other two. Hated the dad too, by all accounts. Mind you, Caroline, the younger sister, is a bit mad too.’

She tells Nelson about the dead snakes and the men dancing in the woods.

‘Snakes again,’ says Nelson.

‘Yes, turns out that Danforth Smith was terrified of them.’

With reason, thinks Nelson. Aloud he says, ‘And this Caroline’s a friend of Cathbad’s? Figures.’

‘She wanted her father to give back the Aborigine bones. It sounds like she was obsessed with them.’

‘Do you think she wrote the letters to the curator? And there was a snake found in the room with the body. Maybe that was her too.’

‘I don’t know. She didn’t mention the curator. It seemed to be all about her dad. Like it was all his fault.’

‘It’s always the dad’s fault,’ says Nelson.

Judy thinks of her own genial, horse-loving father. ‘I think dads are OK,’ she says.

She sounds so like her old self that Nelson begins to hope that the silent, withdrawn Judy has gone for good. Maybe now they can get back to police work. He’ll give her some more responsibility. She didn’t do so badly with Operation Octopus, after all. Then she spoils everything by telling him that she’s pregnant.

Flint is delighted to see Ruth and Kate. He has been alone all day, he tells them, purring sinuously about their ankles, starving and neglected. He has, in fact, been asleep in the airing cupboard. Ruth feeds her cat and starts making some pasta. It’s only five o’clock but it’s dark outside. Kate must be tired, she has only had a tiny sleep in the car. Maybe last night will herald a wonderful new era of sleeping through the night. They’ll have supper at six, Kate will be in bed at seven and Ruth can have all evening watching television and drinking white wine. Heaven.

She has almost forgotten Cathbad and the horrors of last night. Nelson is going to be all right. Michelle let her see him, perhaps she might even allow Nelson to have regular contact with Kate. She admitted that he wants to see her. Ruth knows how much that admission cost Michelle, how much it cost Michelle to come to her house and beg her to visit her husband. She would do anything for him, she said. Ruth doesn’t know if she’s ever loved anyone that much. Except Kate, of course.

She half expects Max to ring but he doesn’t. After the last few days, it seems strange to have no one knocking on the door demanding help or babbling about the Dreaming. After supper, Ruth tries to read a Percy the Park-Keeper book to Kate but she’s more interested in charging around the room with her plastic vegetables. Ruth is determined not to switch on the TV but Kate does it for her (she loves the remote) and soon they are both dozing in front of In the Night Garden . Ruth forces herself to her feet. She’s got to keep Kate awake for a little longer. Routine, she tells herself sternly, it’s all about routine. She puts Kate in her cot while she runs the bath and they both have a strenuous half-hour playing with water. Kate’s eyes start drooping as soon as Ruth puts her into bed. She is asleep before Ruth has read two pages of After the Storm . Ruth finishes the book anyway. She loves it that all the animals find a home in the big tree. She doubts that Norfolk Social Services will be so efficient after last night’s high winds.

Ruth tiptoes out onto the landing. All evening she has avoided looking into the spare room but now she opens the door quietly. The bed is neatly made but lying on the cover is a single feather, long and beautiful, a pheasant’s perhaps. Ruth stays looking at it for a long time.

Nelson’s last visitor is the most surprising. Chris Stephenson, swaggering through the doors as if he’s paying a state visit. Disappointingly, two of the nurses recognise him and flutter around calling him ‘Doctor’ Stephenson. They even offer to get him a cup of tea, although the old woman with the trolley is long gone.

‘Hi Nelson,’ Stephenson greets him. ‘Not dead yet?’

‘Not yet.’

‘Bet you can’t guess why I’m here.’

‘Was it to bring me flowers?’

‘Not allowed. Health and safety.’ Stephenson hasn’t brought any sort of present, not even grapes. Nelson guesses that this call is about business rather than concern for his well-being.

The nurses bring tea in chipped green cups. Stephenson makes a big thing about not needing sugar because he’s sweet enough already. For the first time that day, Nelson feels sick.

‘Your friend Ruth Galloway,’ says Stephenson by way of introduction, slurping his tea.

‘What about her?’ asks Nelson cautiously. He doesn’t know how much his colleagues know about his relationship with Ruth. He thinks that Judy has suspicions about Kate’s parentage; Clough has probably never given it a thought.

‘Remember the bishop? The one that turned out to be a tranny? Well, Ruth sent off some of the material to be analysed. The silk stuff that was wrapped round the bones. Results came back today and guess what they found?’

‘Surprise me.’

‘Traces of a fungus called aspergillus.’

He leans back as if expecting a reaction. Nelson looks at him coldly. ‘That doesn’t mean a lot to me, Chris.’

‘They’re spores, incredibly toxic. They can stay alive for hundreds, thousands, of years. As soon as the spores come into contact with the air, they enter the nose, mouth and mucous membranes. They can cause headaches, vomiting and fever. In people with a weakened immune system, it can result in organ failure and death.’

Nelson looks at him, ‘Danforth Smith.’

‘Yes. He was diabetic, you say. That would have compromised his immune system. He died from heart failure. Could have been brought on by contact with these spores. If we’d done an autopsy, we’d have known.’ He sounds regretful.

Читать дальше